Settling for Silence: How Police Exploit Protective Orders

The national outcry and months of Black Lives Matter protests against police brutality that followed the police killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor are a resounding demonstration of the public’s interest in combatting police violence, particularly excess force used on Black Americans. While media attention on police killings increased after Ferguson Officer Darren Wilson killed Michael Brown in 2014, one piece of the story is often missing: the story of the officers. In particular, the public rarely learns details about the involved officers’ personnel, disciplinary, or misconduct histories. Strong state confidentiality laws mean that the public cannot access these records. But civil rights suits against police officers should provide one way for the public to learn about officers’ misconduct.

This Note shows, however, that police combine protective orders and settlement to bind plaintiffs to silence and keep misconduct records from becoming public. Using a case study of 42 U.S.C. § 1983 suits filed against the New York City Police Department, I find that protective orders are common, and that officers and their city attorneys use them strategically. A textual analysis shows that every protective order explicitly protects police personnel and misconduct records. And cases with protective orders have statistically significantly higher settlement amounts than those without. These results are consistent with a conclusion that NYPD officers, and the City of New York, may pay more to keep misconduct records secret. The standards to modify a protective order are burdensome, and plaintiffs’ and judges’ incentives align against fighting or denying protective orders. Because of these roadblocks, the public has no opportunity to learn about problem officers’ past misconduct that comes to light during civil rights litigation. To facilitate the necessary changes to protect the public and reform or abolish police, the federal government should create a national database of police misconduct records.

Table of Contents Show

Introduction

Americans who watched the video of Minneapolis Police Officer Derek Chauvin fatally driving his knee into George Floyd’s neck[2] or heard the news that Louisville Police Officers Brett Hankison, Jonathan Mattingly, and Myles Cosgrove shot and killed Breonna Taylor in her apartment shortly after midnight[3] were undoubtedly enraged, but likely not surprised. Following the string of police killings of Michael Brown,[4] Laquan McDonald,[5] Eric Garner,[6] and Tamir Rice[7] in 2014, the Black Lives Matter Movement brought a renewed public consciousness to police brutality—though many Black communities and other communities of color needed no reminder.

While police brutality and police killings are not a new problem, the American media and general public seem to rediscover police violence in waves. President Herbert Hoover’s National Commission on Law Observance and Enforcement documented police abuses in its Report on Lawlessness in Law Enforcement in 1931.[8] Modern policing had only begun a century earlier, but its first one hundred years were marked by serious police misconduct.[9] The civil rights era brought graphic images of police brutality to the American public as police attacked peaceful protesters with dogs and fire hoses.[10] And again, the video footage of four Los Angeles police officers brutalizing Rodney King in 1991 placed police violence and misconduct in the public mind.[11] As Americans have begun to carry smartphones, bystanders—and even victims like Sandra Bland[12]—have continued to capture concrete evidence of police violence.[13]

The national response to the police killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor has demonstrated more than just public interest in police killings. Nationwide, Americans, led by community activists of color and the Black Lives Matter movement, have demanded police reform. From May 26, 2020, the day after Floyd’s killing, through June 9, 2020, hundreds of thousands protested police brutality against Black individuals.[14] Protests occurred in two thousand cities and towns in the United States.[15] Protesters chanted the names of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and a litany of other victims of police brutality.

But the names and histories of the officers responsible for civilian deaths tend to be less well-known than those of their victims. This is not because the public is uninterested in officers who use excessive force. Instead, police have successfully mobilized a variety of tactics to keep officers’ on-duty misconduct secret. Strict state confidentiality laws keep officer misconduct records concealed in most states.[16] And prosecutors’ failure to indict officers who kill civilians keeps details about these officers from coming out at a criminal trial.[17] Even when the state prosecutes officers, rules of evidence governing relevancy can prevent prosecutors from introducing evidence of prior police misconduct.[18]

Federal civil rights suits against police are one way that the public could gain information about misconduct that local police officers and departments work hard to conceal. Section 1983 of Title 42 (section 1983) allows individuals to sue government officials for violations of their constitutionally protected rights. Using this private right of action, civilians who face police force can sue the perpetrating officers and the departments that employ them without the political baggage that local prosecutors face when deciding whether and how to prosecute police officers.[19] Because FRCP 26(b) authorizes broad discovery, victims of police brutality who sue police can obtain police misconduct records and department training materials before federal trials.[20]

Though federal civil rights suits are, in theory, a tool for increasing transparency regarding police misconduct, in practice, the public learns little from them. This Note finds that the evidence of past police misconduct or harmful departmental policies that civil rights plaintiffs obtain during pretrial discovery typically must remain confidential. This is because a large proportion of plaintiffs suing police agree to settlement terms that keep police personnel information, misconduct, and training records secret. Using a case study of section 1983 suits brought against the New York City Police Department, I find that stipulated protective orders covering police records are common in these suits. Strikingly, cases with protective orders have statistically significantly higher mean settlement amounts than those without. This finding correlates with the possibility that NYPD police officers, and their city attorneys, prefer to pay out higher settlement awards that bind parties to secrecy than risk the chance that damaging misconduct records will become public.

To explore the role that protective orders play in civil rights suits against police, this Note proceeds in five parts. Part One describes the current legal standards for issuing protective orders and the policy justifications for permitting them in federal litigation. Part Two explains that protective orders are an ill fit for section 1983 civil rights suits against police due to the public’s interest in obtaining officer misconduct records. Part Three explores the prominence of protective orders in federal civil suits against police through an empirical, case-study analysis of suits against New York City police officers between 2014 and 2019. Part Four argues that under current law, the incentives of all parties enable police to exploit protective orders to favor their confidentiality interests over public health and safety concerns. Part Five proposes a solution. Specifically, Congress should create a national database for police misconduct records. The ever-increasing death toll of civilians, particularly Black Americans, killed by police and the mounting public outcry over police brutality demand nothing short of a systemic overhaul. This proposed national misconduct database would be a step toward increasing transparency, putting public pressure on officers who have engaged in misconduct, and preventing future police violence.

I. Constraining Pretrial Discovery Through Stipulated Protective Orders

A. The Standards and Procedures that Govern Protective Orders

Parties to civil litigation may “share what they learn in discovery with other persons, including news media, as they see fit.”[21] Courts in a majority of federal circuits have affirmed a litigant’s ability to use pretrial discovery for any lawful purpose.[22] Some authorities ground a litigant’s ability to disseminate pretrial discovery in the First Amendment[23] while others derive this power from the absence of language in the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, which “limit[s] a party’s use of information or documents it obtains through discovery.”[24] While the source of the power is not settled, the power itself seems uncontroversial[25] and can be broadly exercised. For example, in an Eastern District of Virginia case, the court found that the plaintiffs—former employees of the private security companies owned by Erik Prince—could publish on their counsel’s website discovery materials that a valid judicial order did not make confidential.[26] Thus, even though “pretrial discovery . . . is usually conducted in private,”[27] parties may disseminate and “use discovery information as they wish” when it is not protected.[28]

But judicially issued protective orders sharply curtail litigants’ ability to share pretrial discovery with non-parties. The Supreme Court has made clear that a court may restrict a litigant’s power to disclose pretrial discovery by issuing a protective order that complies with Rule 26(c) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (FRCP).[29]

Under FRCP 26(c)’s permissive terms, a court may choose to keep discovery materials confidential upon a party’s showing of “good cause . . . to protect a party or person from annoyance, embarrassment, oppression, or undue burden or expense.”[30] In the Third Circuit,“[g]ood cause means ‘that disclosure will work a clearly defined and serious injury to the party seeking closure.’”[31] The Sixth and Ninth Circuits have adopted similar definitions.[32] To demonstrate this injury, the moving party must “articulate specific facts to support its request.”[33] The rule gives courts “substantial latitude to fashion protective orders.”[34] Once entered, a protective order may keep discovery material confidential long past the end of the litigation. Protective orders stay in place unless a party, or an interested intervenor, moves to lift or modify the protective order.[35]

Parties may also present a stipulated protective order to the court. Under these orders, parties agree to confidential terms. Theoretically, courts must find good cause exists before issuing such an order, even when parties agree to keep discovery confidential. In fact, in 1995, the Advisory Committee on Civil Rules reaffirmed that courts must engage in this inquiry. It rejected a proposal to modify Rule 26(c) to permit courts to grant a protective order for either good cause or “on stipulation of the parties.”[36] A letter from the Committee on Rules of Practice and Procedure of the Judicial Conference of the United States explained that members “voted to delete the words ‘on stipulation of the parties’” because of concern that such a rule “would tie the hands of trial judges reluctant to accept agreed orders.”[37] Therefore, the plain text and history of FRCP 26(c) show that courts must find good cause to grant a protective order, regardless of whether it is contested or stipulated.

Some federal courts have affirmed this rule. The Seventh Circuit has squarely held that district courts must “independently determine if ‘good cause’ exists” before granting a stipulated protective order.[38] Decisions in the Third and Federal Circuits similarly suggest but do not clearly establish, that district courts must find good cause for stipulated protective orders.[39]

However, other federal courts have ruled to the contrary. The Ninth Circuit has held, without citation to authority, that “[w]hile courts generally make a finding of good cause before issuing a protective order, a court need not do so where . . . the parties stipulate[d] to such an order.”[40] The Eleventh Circuit has also shifted the requirement that parties establish good cause to a district court’s consideration of “a motion to modify . . . a stipulated protective order” instead of the moment the district court first grants it.[41] The Second Circuit has intimated that “parties might enter into an agreement or stipulate to protect the confidentiality of discovery materials before presenting a proposed protective order to a court,” and later use this agreement to prevent the court from modifying it on reliance grounds.[42] The Second Circuit’s approach acknowledges that a court must approve a stipulated protective order but simultaneously suggests that the parties can prevent a court from engaging in a thorough good cause analysis before approving it. And while the Sixth Circuit in an earlier case appeared to condemn courts issuing stipulated protective orders without finding good cause,[43] it now acknowledges that “courts often issue blanket protective orders that empower the parties themselves to designate which documents contain confidential information.”[44] Therefore, in these circuits, when all parties agree to a protective order, they “postpone, perhaps indefinitely, the obligation to make a particularized showing” explaining why a protective order is justified.[45]

The trend toward permitting parties to stipulate to protective orders without a judicial finding of good cause leads to a “disturbing[]” pattern in which “some courts routinely sign orders which contain confidentiality clauses without considering the propriety of such orders, or the countervailing public interests . . . .”[46] A review of one hundred proposed stipulated protective orders issued in federal courts in January 2018 found that courts and parties use “generic language to describe the need for the protective order” and fail to reach the particularized good cause standard.[47]

But even when courts do engage in the required good cause analysis before granting a stipulated protective order, they typically consider only the moving parties’ interests and disregard broader public interest concerns. The Third Circuit’s Pansy factors stand alone in asking district courts to consider the “public importance” of a case, its impacts on general health and safety, and litigants’ status as public officials before granting a protective order.[48] This singular focus on the litigants’ interests follows from Seattle Times Co. v. Rhinehart’s holding that the public has no First Amendment or common law right to access pretrial discovery.[49] And because the amended FRCP 5(d) no longer requires parties to file discovery documents until “they are used in the proceeding,”[50] the public cannot claim that pretrial discovery is a judicial document subject to public access.[51] This precedent suggests that private parties can invoke judicial power to endorse their private agreements with little to no consideration of public interest.

B. The Policy Justifications for Protective Orders

Parties began using stipulated protective orders in complex, commercial cases with a large volume of discovery.[52] The drafters of the FRCP recognized the expanding use of protective orders in commercial litigation when amending Rule 26(c) in 1970.[53] While the advisory committee comment explains that they amended the rule “to give [protective orders] application to discovery generally,”[54] they also added language explicitly acknowledging that courts may issue protective orders to protect trade secrets, confidential research and development, or commercial information.[55] This new language “reflect[ed] existing law” applying protective orders to “confidential commercial information” exchanged in litigation.[56]

But stipulated protective orders are now “commonplace in the federal courts” and associated with litigation of all types.[57] And it’s not hard to see why. Stipulating to confidentiality accelerates discovery and satisfies both parties.[58] The proponent gets to keep discovery materials confidential, and the opponent may access information it could not otherwise receive without extended litigation.[59] In many ways, a stipulated protective order is a contract to not distribute discovery materials. But unlike a standard private contract, stipulated protective orders receive judicial approval and are subject to judicial monitoring and enforcement.[60] Parties that violate a protective order are subject to contempt—a more immediate and potentially harsher sanction than breaching a contract.[61]

The proliferation of protective orders in civil litigation reflects an assumption that such litigation is primarily a mechanism for resolving private disputes. The fact that discovery and “information exchange . . . takes place out of the public eye and without involvement by the judge” supports this perspective.[62] And despite the Federal Rules’ operation as a “broad discovery regime,” scholars like Arthur Miller argued that they “never intended that rights of privacy or confidentiality be destroyed in the process.”[63] Under this understanding of the court system, allowing litigants to contract for confidentiality is more important than facilitating public access. This is because it allows litigants to resolve disputes without sacrificing their privacy,[64] protects their property,[65] and improves court efficiency while reducing costs.[66] For advocates of protective orders, the paradigmatic litigant in need of protection is businesses with commercially valuable information.[67]

Richard Marcus, a supporter of protective orders, noted that civil discovery does sometimes alert the public to concerns and provides information the public would not otherwise have access to.[68] But he contended these are “collateral effects” that “should not be allowed to supplant [the] primary [dispute-resolution] purpose” of litigation.[69] Marcus argued that regulators, rather than courts, should be the means by which the public is informed of issues that implicate public health and safety.[70]

Arguments defending litigants’ ability to stipulate to protective orders assume that the purpose of civil litigation is to resolve private disputes. These policy rationales may resonate for commercial disputes between private parties and relationship-based litigation like divorce. But Part II questions whether these same arguments justify courts endorsing litigants’ confidentiality agreements in section 1983 suits, which fundamentally concern the behavior of public officials.

II. The Public’s Interest in Police Misconduct Records Make Stipulated Protective Orders an Ill Fit for Civil Rights Suits Against Police

Stipulated protective orders should not be “commonplace” in civil suits against police. Section 1983 suits against police officers are unlike the typical suits that the private dispute resolution model contemplates because a section 1983 suit involves a public officer by definition. Under 42 U.S.C. § 1983, local or state officials acting in their official capacity “under color” of law are liable for depriving the “rights, privileges, or immunities secured by the Constitution and laws” of any person in the United States.[71] Common causes of action in section 1983 suits filed against police officers include: use of unreasonable force in violation of the Fourth or Fourteenth Amendments[72] and unlawful arrests, stops, frisks, searches, or seizures in violation of the Fourth Amendment.[73]

Because “[l]awfulness of police operations is a matter of great concern to citizens in a democracy,”[74] the concept of civil litigation as resolving private disputes seems to be an ill fit for suits that involve public officers. These cases “represent[] a balancing feature in our governmental structure whereby individual citizens are encouraged to police those who are charged with policing us all.”[75] Instead, section 1983 suits are better conceptualized under a model of public law litigation.

Public law litigation introduced an alternative approach to the private dispute model of litigation.[76] As first described by Abram Chayes, the original concept of public law cases had these key attributes:

These . . . cases involved amorphous, sprawling party structures; allegations broadly implicating the operations of large public institutions such as school systems, prisons, mental health facilities, police departments, and public housing authorities; and remedies requiring long-term restructuring and monitoring of these institutions.[77]

Civil rights cases and the structural remedies they demanded first exposed federal courts to public law litigation and set the characteristics of the model.[78] These suits proliferated following the 1966 amendments to the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.[79] Modifications to nonparty joinder in Rule 19, class actions in Rule 23, and nonparty intervention in Rule 24 made “party structure more flexible” and enabled large groupings of plaintiffs to sue governmental bodies to effect policy change.[80]

Section 1983 suits against police do not, and cannot, always satisfy each of the typical characteristics of public law litigation. A private litigant’s power to sue police departments for injunctive relief, and therefore create court-enforced policy changes, has been stymied by City of Los Angeles v. Lyons’s equitable standing doctrine.[81] Following Lyons, private individuals can only seek injunctions against police departments when they can show that they are “realistically threatened by a repetition” of the same injury they already suffered.[82] To receive injunctive relief, those who have suffered police abuse must now allege that “all police officers” in the locality “always [harm] any citizen with whom they happen to have an encounter” in the same way or “that the City ordered or authorized police officers to act in such manner.”[83] These doctrinal developments have slowed “institutional reform litigation in policing”[84] and prevented individuals from acting as “direct agent[s] in effecting meaningful social change through America’s courts.”[85]

But key attributes of public law litigation remain in section 1983 suits against police. As Chayes described, these modern suits still “do not arise out of disputes between private parties about private rights. Instead, the object of litigation is the vindication of constitutional or statutory policies.”[86] The defendants in these suits are police officers, police departments, and often the city, county, or state government that grants police their authority to operate. The causes of action in section 1983 suits often extend beyond discrete officers and implicate police department training and policy. Therefore, these suits often “seek to vindicate important social values that affect numerous individuals and entities.”[87]

And section 1983 suits against police still have the power to spur police departments into changing their policies and practices. Suits for money damages can force police departments to enter into settlement agreements with provisions for reform. These cases include a suit that required “Wilmington Police [to] evaluate its deescalation tactics and training for officers” [88] and a suit that forced the “Los Angeles Police Commission [to] . . . agree[] to ban a controversial form of restraining” suspects known as “hogtying.”[89] Certain judicial decisions in section 1983 cases have even required police departments to release documents detailing systemic misconduct. In a federal case brought against the Houston Police Department and City of Houston for the shooting of Kenny Releford, a federal judge refused to seal certain discovery materials despite the City of Houston’s attorneys’ and the police union’s opposition.[90] Following the court’s ruling, “the Houston Police Department was compelled to release previously secret internal reviews of Releford’s shooting as well as of other unarmed Houstonians.”[91]

But for these suits to have a chance at sparking change, there must be publicity. A successful suit against police or simply credible allegations of harm before a court “will focus public attention on the problems,” and “increased scrutiny will generate diffuse but sometimes powerful pressures for responsible behavior.”[92] Further, as Joanna Schwartz has found, “most departments ignore lawsuits that do not inspire front-page newspaper stories, candlelight vigils, or angry meetings with the mayor.”[93] Therefore, transparency in private citizen suits against police is critical. Making the public privy to filings and discovery in these suits can do necessary work to “help citizens police the government by forcing governmental entities to release information that would otherwise be kept secret.”[94]

The public has an interest in police misconduct and disciplinary records produced in discovery because access to these records enables the public to identify abusive officers. This access is necessary to hold these abusive officers, and, more importantly, the departmental policies that produce them, to account. But due to the dearth of criminal trials brought against police officers, police union record destruction policies, and strict state confidentiality protections for officers, civil discovery may provide one of the few remaining avenues through which misconduct records could be disclosed.

A. Identifying Abusive Officers

Residents of a given community and the public at large have an interest in knowing about dangerous officers, as well as police departments’ systematic failures to train or reprimand officers for misconduct or crime. Knowing this information can give the public critical data that it can use to pressure police departments and governments into terminating abusive officers and reforming training and oversight policies.[95] And the public has a particular interest in police misconduct records produced in section 1983 litigation discovery because these suits tend to identify officers who have engaged in or have histories of misconduct. Specifically, police officers who seek to protect their records as defendants in section 1983 suits may desire confidentiality because they have disciplinary histories that if publicly exposed, could reveal their past serious misconduct.

Many police officers involved in high-profile killings have previously been the subject of both civilian complaints and lawsuits. Derek Chauvin, the Minneapolis officer who killed George Floyd “received at least 17 complaints” in his nearly twenty years on the force.[96] He was “involved in the fatal shooting” of another person and shot a suspect who survived.[97] He was also “named in a brutality lawsuit.”[98] While Minnesota was one of the few states that published civilian complaint data at the time of the incident,[99] the public data itself could not predict Officer Chauvin’s future dangerousness because it both undercounted the number of complaints brought against Chauvin and lacked details about the facts of the incidents.[100]

Tou Thao, one of the three other officers involved in Mr. Floyd’s killing, had six misconduct violations and was sued for brutalizing a man in 2017.[101] In that 2017 suit, all parties entered into a protective order that made “Minneapolis Police Department Personnel files,” “Minneapolis Police Department Internal Affairs records,” and “Minneapolis Civilian Review Authority and Office of Police Conduct Review records” confidential.[102] The order required counsel to “return all Confidential Materials” once the action terminated, and prohibited parties from using the materials “or information derived from them . . . for any other purpose other than for this Action.”[103] Minneapolis settled the case for $25,000.[104]

Similarly, Jason Van Dyke, the Chicago police officer who murdered Laquan McDonald, had a history of complaints about excessive force. “[I]n his 17 years on the police force, [he] accumulated 20 documented citizen complaints against him, mostly for excessive force.”[105] A rare jury trial also found him liable for using excessive force during a traffic stop.[106] This case bound the parties with a protective order during pretrial discovery.[107] The order protected “personnel files, disciplinary actions, histories, [and] files generated by the investigation of complaints of misconduct by Chicago police officers.”[108] It explicitly determined that the Illinois Personnel Records Review Act,[109] and Section 7 of the Illinois Freedom of Information Act,[110] protected the records.[111] The protective order still covers those discovery materials that did not become part of a judicial record.

Empirical analysis substantiates the intuition that officers with more misconduct records are more likely to use excessive force against civilians in the future. Kyle Rozema and Max Schanzebach analyzed fifty thousand civilian allegations of misconduct made against Chicago Police Officers.[112] They found “a strong nonlinear relationship” between officers who were the subjects of civilian allegations and officers who engaged in serious misconduct, as measured by the officers being named as defendants in section 1983 suits.[113] A nonlinear relationship in this case means that each increase in civilian complaints against an officer did not correspond with an equal increase in the probability that the officer would be a defendant in a civil rights lawsuit. Instead, the “worst 5 percent of officers” in terms of the volume of complaints against them were subject to the most litigation, and the “worst 1 percent of officers . . . generate[d] almost 5 times the number of payouts and 4 times the total damage payouts in civil rights litigation.”[114]

Rozema and Schanzenbach’s research links histories of misconduct to abusive officers who are sued under section 1983. Yet, it is precisely these histories of misconduct that protective orders obscure. Had the public been privy to the details of Officer Chauvin’s, Officer Thao’s, and Officer Van Dyke’s misconduct records prior to their killings of George Floyd and Laquan McDonald, respectively, Minneapolis or Chicago residents could have pressured the departments to fire these officers or establish robust mechanisms for evaluating and terminating problem officers. The section 1983 suits against them could have filled this informational hole but did not because of protective orders.

B. Holding Officers Accountable

Misconduct and training records provide a key source of information that the public needs to hold police officers accountable for their actions. Without record transparency, police departments can “claim that a fully functional police accountability system exists––whether true or not––without any contradictory evidence publicly accessible.”[115] And “[e]ven if it is a functional system, depriving the public of any ability to judge for itself is not justice.”[116] The public and policymakers need access to records to judge whether internal police disciplinary procedures are effective.

Outsiders must apply external pressure because internal investigations rarely punish officers. Rachael Moran identified that “the DOJ has . . . found repeated instances in which civilians’ complaints reported through an internal intake process were never investigated.”[117] When officers are investigated, “the officers investigating these reports have an inherent inability to conduct impartial investigations”[118] and ultimately resist “disciplining their own officers . . . [for] even the most obvious misconduct.”[119] Empirical evidence confirms that police departments reject civilian complaints at high rates. Law enforcement agencies in California upheld only 8.4 percent of civilian complaints between 2008 and 2017.[120] In Chicago, the complaint process takes “about one year” to complete and may be followed by “a lengthy appeals process for any resulting discipline.”[121] And in New York, between 1975 and 1996, the department only terminated 2 percent of NYPD officers following misconduct allegations.[122]

It is possible that police departments discipline few officers following complaints because the complaints themselves are frivolous. But researchers like Phil Stinson have found that a small percentage of officers are the subjects of consistent complaints,[123] suggesting through sheer repetition that the complaints against these officers have merit. Further, for the police department or associated complaint review board to treat a claim formally as a complaint, the complaining party must speak with an investigator, often at the investigating body’s office or at the police department.[124] Because a complaint is not officially a complaint when the agency receives a letter, email form, or phone call, the effort required to make a complaint may serve as a fair proxy of how serious these claims are.

Having access to disciplinary, personnel, and training records would provide the evidence necessary for future litigants to successfully seek injunctions against harmful police department policy under Monell v. Department of Social Services.[125] Section 1983 suits on a respondeat superior theory cannot hold local governments liable for the actions of individual officers.[126] However, Monell allows section 1983 suits against a local government or municipality that “implements or executes” an unconstitutional “policy statement, ordinance, regulation, or decision.”[127] To meet the requirements of Monell liability, plaintiffs need documents that can prove the department engaged in an unconstitutional custom or failed to hire adequately, train, and supervise.[128] Giving the public access to police misconduct and training records can therefore remove an informational block to succeeding in these actions. With adequate access to proof of departmental policy or custom, Monell suits can encourage broader departmental change by enjoining unconstitutional departmental conduct.

C. Insufficient Alternative Avenues of Disclosure

Unfortunately, section 1983 suits provide one of the only remaining ways that members of the public may gain access to officers’ disciplinary and misconduct records, as well as police department training manuals.

Criminal cases have not been a strong mechanism for bringing police misconduct records to light because the criminal legal system was not designed to punish police officers. Local and federal prosecutors have been resistant to charging officers who kill or injure civilians. A 2010 study evaluated 8,300 misconduct accusations based on a dataset that collects credible incidents of misconduct from media reports. Of this subset of publicized, credible police misconduct accusations, only 39 percent resulted in legal action of any kind.[129]

Prosecutors also may present half-hearted cases to grand juries that fail to indict police officers for assault or murder. For example, the District Attorney’s Office in Hennepin County where Officer Chauvin killed George Floyd did not return an indictment for a single officer for any of the forty-two officers involved in killings in the county between 2000 and 2016.[130] Prosecutors similarly failed to return indictments for the officers who killed Eric Garner and Michael Brown.[131] And while grand jury records, and the experiences of grand jurors themselves, are presumptively secret,[132] a juror was permitted to speak about their experience on the grand jury in the case against the Louisville police officers who killed Breonna Taylor.[133] The grand jury returned only three counts for wanton endangerment against Brett Hankison for shooting at Ms. Taylor’s apartment and hitting a neighboring apartment during the midnight.[134] But the grand juror contended that the prosecutor did not present evidence to support a homicide offense or explain those laws.[135] In fact, the juror stated that other grand jurors “asked about additional charges” but were told “there would be none because the prosecutors didn’t feel they could make them stick.”[136] This juror was only allowed to speak after a court granted their motion to describe their experience over the objections of the Kentucky Attorney General Daniel Cameron, who led the prosecution.[137] These anecdotes lend credence to Kate Levine’s argument that due to the close police-prosecutor relationship, conflict of interest laws should disqualify local prosecutors from prosecuting officers, but they rarely do.[138]

This combination of grand jury secrecy and lack of prosecution creates another barrier to public disclosure. Thus, criminal suits against police officers rarely serve as fora for revealing details of police officer crime and misconduct.

Police unions also include a variety of clauses in their union contracts to keep misconduct records secret. Stephen Rushin’s analysis of 178 police union contracts from U.S. cities with over one hundred thousand residents shows that many police contracts provide for regular destruction of misconduct records.[139] Specifically, “eighty-seven . . . collective bargaining agreements” of the 178 contracts he reviewed (48.9 percent) “require[d] the removal of personnel records” at set times.[140] This means that certain officers “can have his or her personnel file wiped clean” every two years even when records contain sustained claims and show a pattern of misconduct.[141] Further, “many police union contracts prevent even police chiefs from fully using officer disciplinary records.”[142]

State confidentiality laws also prevent the public from accessing misconduct files and disciplinary information about the police officers that serve them. Currently, thirty-eight states make disciplinary records completely confidential or sharply curtail public access.[143] Some states have adopted statutes that explicitly make officers’ records confidential, like a Delaware statute entitled “Law-Enforcement Officers’ Bill of Rights.”[144] Other statutes shield personnel or disciplinary records of all state or municipal employees, which necessarily include police officers, from public view.[145] Departments in Arkansas, Hawaii, and Indiana only make the records of terminated or suspended officers public.[146]

Police departments often broadly construe language in their states’ public records acts or state constitutional rights to privacy to make disciplinary records confidential in practice.[147] Departments in D.C. rely on broad privacy protections in public record laws to deny requests for records.[148] Kentucky police departments will respond to requests with “heavily redacted records” that merely list “disciplinary actions.”[149]

Some courts have occasionally pushed back on broad readings that exempt certain police records from disclosure. The First District Appellate Court of Illinois granted a plaintiff access to complaints against Chicago Police officers, rejecting the CPD’s argument that the Illinois FOIA exceptions should be read broadly to include complaints.[150] But others, like the court in Maryland Department of State Police v. Dashiell, have shielded records even from the individual who filed the complaint against an officer.[151]

Only twelve states make police disciplinary records subject to disclosure under a state’s public disclosure law.[152] But there are still limits on what records may reach the public. For example, in Florida, Georgia, Maine, and Minnesota, disciplinary records are available only after an internal investigation is finalized while records in Arizona are protected until an appeals process is completed.[153] And in Arizona, public records are subject to a balancing test that considers an officers’ interest in “confidentiality [and] privacy.”[154] In Utah, only substantiated disciplinary records are subject to public disclosure.[155]

Further, civilian defendants in criminal cases face a high standard for obtaining misconduct records to impeach police witnesses despite their constitutional rights to due process and compulsory process. Criminal defendants in state court have a Sixth Amendment compulsory process right and a Fourteenth Amendment due process right to “a meaningful opportunity to present a complete defense.”[156] This includes “[t]he right to offer the testimony of witnesses, and to compel their attendance”[157] and requires the prosecution to “deliver[] exculpatory evidence into the hands of the accused.”[158] To vindicate these rights, defendants must have access to records about officers who will testify against them at trial to enable impeachment. But Rachael Moran has found that many states “make it extremely difficult for defense counsel to access these confidential [police personnel] records.”[159] Specifically, criminal defendants in Colorado must allege a “‘specific factual basis’”[160] showing that the records exist and that they provide material evidence. Criminal defendants in Arizona, Connecticut, Georgia, and North Carolina must show that the records have information that is relevant to the theory of defense.[161]

Even in states like California that have amended more restrictive confidentiality laws protecting police records, police still challenge practices that enable criminal defendants to obtain impeachment evidence on testifying officers. For example, in Association for Los Angeles Deputy Sheriffs v. Superior Court, the Association for Los Angeles Deputy Sheriffs sued the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department to prevent it from disclosing a list of officers whom prosecutors have determined have impeachment material regarding their credibility as a witness.[162] The list, devised as a way for prosecutors to comply with their disclosure requirements under Brady v. Maryland,[163] disclosed very little: only “(a) the name and identifying number of the officer and (b) that the officer may have relevant exonerating or impeaching material in [that officer’s] confidential personnel file.”[164]

The California Supreme Court held that the prosecutors could maintain such a list.[165] But defendants who receive information about this list do not receive the impeachment material directly from the prosecutors. This is because the Pitchess statutes restrict even “a prosecutor’s ability to learn of and disclose certain information regarding law enforcement officers.”[166] Therefore, armed with the information from the list, defendants must still obtain the “personnel records and records of citizens’ complaints”[167] through California Public Record Law if the material is subject to public disclosure under Section 832.7 or comply with procedural requirements under California’s Pitchess statutes.[168] If the defendant must comply with Pitchess, the “party seeking disclosure . . . must file a written motion . . . identify[ing] the officer or officers at issue . . . describ[ing] the ‘type of records or information desired.’”[169] The party must also show good cause for discovery by making allegations of materiality and reasonable belief of the information’s existence.[170] Despite reform, California defendants continue to face obstacles in accessing police personnel records.

Confidentiality laws, prosecutorial resistance to charging, union conditions mandating record destruction, and protective orders combine to keep the public in the dark about dangerous officers in their communities. This opacity can be deadly. Courts can mitigate the effects of widespread secrecy around police records by not granting protective orders in civil rights suits against police or granting motions to modify or lift orders protecting these records. This discretion is a power that courts can and should use to protect the public interest.

Because of the strong public interest in section 1983 suits against police, Eastern District of New York Judge Weinstein in King v. Conde found that “‘[r]outinely’ issuing protective orders will not necessarily promote justice or the proper balance of interests.”[171] While King predates the 2000 amendment of FRCP 5(d), eliminating the discovery filing requirement,[172] Judge Weinstein’s admonition should remain a guiding force for discovery in civil suits involving the police. The mere fact that discovery is no longer publicly filed does not eliminate the public nature of a section 1983 suit or the public’s interest in identifying dangerous officers and holding them accountable. But, as I detail below, the countervailing legal principles and practical realities of case management suggest that courts will grant stipulated protective orders in a civil rights case against police without considering the public’s interest.

III. Routine Stipulated Protective Orders in Federal Suits Against Police: A Case Study

To begin to understand the role stipulated protective orders play in federal civil rights suits against police, I analyzed cases brought against New York City Police officers in the Eastern and Southern Districts of New York. I hypothesize that the presence of a protective order results in a higher settlement amount than cases without such orders. I ground this hypothesis in two related assumptions. I assumed that police officers will move for stipulated protective orders when plaintiffs request an officer’s misconduct and disciplinary records. I also assumed that officers are willing to pay a higher settlement award to settle a case with a guarantee that their misconduct records will remain confidential. I tested this hypothesis using a randomly selected probability sample of section 1983 cases filed against the NYPD between 2014 and 2019.

I found that stipulated protective orders are common in suits against the NYPD, but that New York City, representing the officers, moves for them strategically. In reviewing stipulated protective orders’ texts, I found that all protective orders explicitly protect NYPD disciplinary and misconduct records. Ultimately, I found that cases with protective orders terminate in statistically significantly higher settlement values than cases without orders in place.

The following presents my methodology, descriptive statistics, findings from reviewing the text of stipulated protective orders, results from my statistical analysis, a discussion of potential mechanisms that may explain my findings, and the limitations of the results.

A. Methodology

To determine whether settlement awards meaningfully differ between section 1983 suits with and without protective orders, I randomly selected 20 percent of cases from New York City’s publicly available “NYPD Alleged Misconduct Matters” database.[173] Below, I describe why I chose this subsample, my data collection process and its limitations, and the qualitative and quantitative methods I used to analyze the data.

1. Sample Selection

I selected federal suits against New York Police officers as my case study sample for two reasons. The first reflects a practical data collection concern. While many major cities maintain open data portals,[174] New York City is among the few municipalities that provides a comprehensive dataset of lawsuits filed against its police officers. New York City maintains the “NYPD Alleged Misconduct Matters” dataset pursuant to Local Law 166, which requires the City to publish information regarding suits against the NYPD.[175] At the time of analysis, this database included all “civil actions alleging misconduct commenced against the police department and individual officers” between 2014 and 2018 in both federal and state court.[176] The second reason for selecting this sample is because of the different access that section 1983 plaintiffs in state and federal court have to New York City and New York state police officers’ misconduct records. During this period, Civil Rights Law section 50-a set a high bar for New York state litigants seeking to obtain NYPD misconduct records.[177] But as described further in Part IV.A, federal litigants were not subject to the same confidentiality provisions and could obtain the records through FRCP 26(b).[178] Therefore, to ensure that litigants in my sample had the ability to obtain police misconduct records, whether unrestricted in discovery or through protective orders, I dropped all state cases from my analysis sample and included only section 1983 suits filed against NYPD officers in the Eastern and Southern Districts of New York.

I randomly selected 20 percent of cases within my sample parameters as my analysis sample instead of using the full dataset due to time and resource constraints. The “NYPD Alleged Misconduct Matters” database contains key variables relevant to my analysis, including docket number, litigation start and end date, attorney representation, disposition, and settlement amount.[179] But the dataset did not include any information on protective orders. Therefore, I manually built my analysis sample by searching the available dockets of each randomly selected case, as described more fully in Part III.A.2. I chose 20 percent of the sample to reduce the time-consuming data collection process while ensuring I had enough data to accurately mimic the distribution of the full dataset. I tested whether the 20 percent subset analysis sample is representative of the full sample by comparing the data on relevant descriptive statistics. I present these results in Part III.B.

2. The Dataset, Data Collection, and Limitations

The final sample is limited to suits with a final disposition filed in either the Eastern or Southern Districts of New York. In each case, plaintiffs civilly sued individual officers, and often New York City, for constitutional violations under 42 U.S.C. § 1983. After dropping state court cases, the full dataset represents 2,929 unique civil rights suits brought against NYPD officers in federal court. The original federal suit dataset contained 3,545 cases, but 618 cases had not yet reached a final disposition. I dropped these non-final cases from analysis because they may not have reached a litigation stage where a party would move for a protective order; including them could artificially dampen the rate at which parties moved for protective orders.

Before collecting my protective order data, I randomly assigned a number to each case using the Stata software program’s “uniform” and “rank” functions. To select 20 percent of the 2,929 cases, my initial analysis sample included cases assigned a number between 1 and 595.

To determine whether a litigant in the random sample moved for a protective order, I accessed public docket information for each case. I searched Bloomberg Law dockets, Lexis Court Link, CourtListener.com, and PacerMonitor.com using the sample case’s docket number. When I matched a docket to a case in my sample, I read through the docket for indications of whether either party moved for a protective order or a confidentiality order. I manually collected five variables: (1) the presence or absence of a protective order or confidentiality order; (2) the party proposing the order; (3) whether the proposed order was stipulated to or contested; (4) whether or not the court granted the protective order; and (5) the date of any protective order entered. Where available, I also collected the associated proposed and granted protective orders for textual analysis.

Not every case was available from these sources. When I could not find a docket from any of my source websites, I indicated in my master dataset that the docket was missing. To ensure that 20 percent of my final sub-sample included only cases with a docket available, when I could not find a case, I added a replacement case to my master dataset according to its randomly assigned number. In total, I could not identify twenty-four dockets. This approach runs the risk of skewing results if publicly available protective orders are meaningfully different from protective orders that are not made public. However, because only twenty-four of the 595 cases included in the final analysis sample were unidentifiable. The chance that these twenty-four cases are fundamentally different is low.

During this period, some cases in the Southern District of New York were subject to Local Civil Rule 83.10. The rule applies to civil plaintiffs suing New York City, the NYPD, and individual officers under section 1983.[180] Rule 83.10(11) indicates that for qualifying cases, a specified protective order “shall be deemed to have been issued in all cases governed by this Rule.”[181] While Rule 83.10(11)’s “protective order” protects NYPD officers’ misconduct data and plaintiffs’ medical and arrest records, I did not classify these cases as cases with protective orders issued because they did not meet my established criteria for what constitutes a protective order. Specifically, neither party requested the order, and no court entered the order. Instead, when the stock protective orders from Rule 83.10(11) applied, I treated these “protective orders” as private agreements between the parties instead of a judicially granted and endorsed protective order.

This means I may undercount cases for which the parties believed themselves bound to keep NYPD records confidential. But because my analysis sample includes S.D.N.Y. cases covered by Rule 83.10(11) for which the court did grant a specified protective order on the record, I believe the protective orders actually entered by the court following a party’s motion better reflect the actual strategy and goals of the parties.

The dataset did not include some variables that would enhance this analysis. There are no concrete indicators of the plaintiffs’ or the officers’ races or ethnicities. Therefore, I cannot evaluate whether Black individuals or other persons of color are more likely to sue NYPD officers than White individuals. Further, this dataset does not provide information about the basis for the section 1983 claim or the severity of the alleged injury. Accordingly, the results cannot analyze whether specific categories of misconduct correlate with the presence of protective orders at higher or lower rates. Finally, because the data are limited to suits involving the NYPD, the results cannot be generalized beyond Eastern District of New York (E.D.N.Y.), Southern District of New York (S.D.N.Y.), or NYPD defendants specifically. A nationally representative dataset would be difficult, if not impossible, to compile because comprehensive datasets of each section 1983 suit filed against police officers are not available for every police department in the United States, or even for similarly large departments patrolling major cities. But as discussed in Part IV, there is reason to believe that police and their municipal attorneys across jurisdictions share similar interests in keeping misconduct records confidential.

3. Qualitative and Quantitative Methods

To test my hypothesis that cases with protective orders terminate in higher settlement awards than those without, I used qualitative and quantitative research methods to analyze my sample data.

On the qualitative side, I analyzed the text of forty-eight protective orders entered in my randomly selected sample cases to determine what kind of information parties sought to keep confidential through protective orders. While I could review many case dockets using publicly available sources, full-text protective orders were not commonly available on sites without a paywall. Therefore, the forty-eight protective orders I analyzed represent all the orders I could view. My textual analysis involved reading each order and assigning the text a code if it embodied a relevant analysis category. Codes included: (1) protects NYPD records; (2) protects plaintiff’s information; (3) restricts records use; and (4) describes the protective order legal standard and explains how the order fulfills it.

On the quantitative side, I used an independent samples t-test to compare settlement amounts in cases with and without protective orders. My dependent variable was the log of the settlement price. I used the log of the settlement price because the distribution of settlement values is not symmetrical and skews toward $0, and the settlement values contain extreme outliers. To avoid dropping settlements for $0 after transforming the settlement value to the log, I assigned every $0 settlement a settlement price of $0.01. My independent variables were cases with protective orders and cases without protective orders. The observations are independent because duplicate cases were dropped prior to analysis. I conduct my significance testing at α=0.05.

B. The Full Dataset and the Analysis Dataset

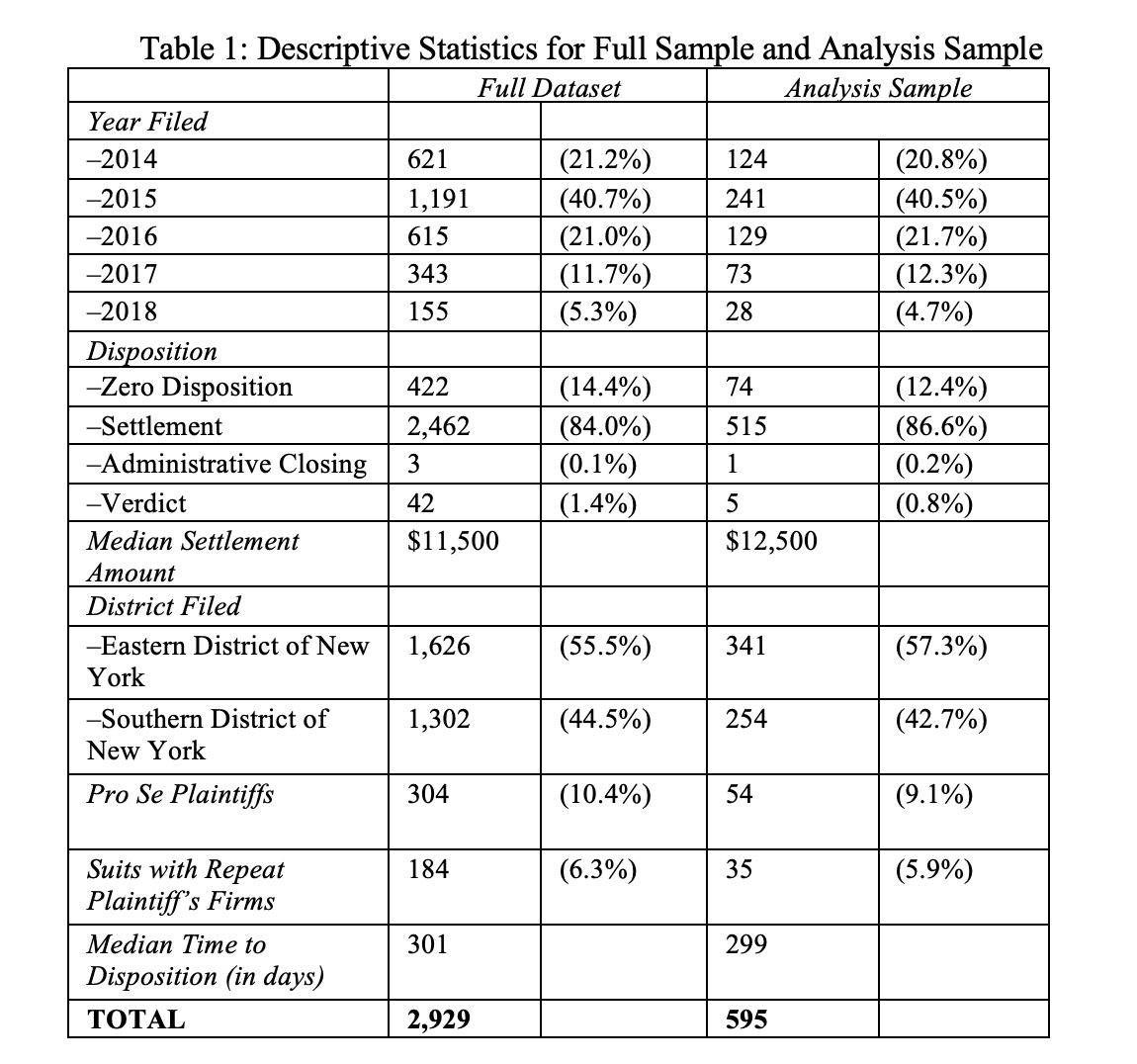

The full dataset contains 2,929 cases filed against NYPD officers, the Department itself, and often the City of New York in federal court. As a result of the final disposition requirement, most cases began between 2014 or 2016 (73 percent). Civil litigants filed 56 percent of the cases in E.D.N.Y. and filed the remaining 44 percent of cases in S.D.N.Y. Parties settled 85 percent of cases. Only 1.3 percent of cases went to verdict. The median settlement amount was $11,500. Median litigation lasted 301 days. Approximately 10 percent of plaintiffs were pro se. Table 1 provides descriptive statistics for the full dataset compared to the randomly selected analysis sample.

The final analysis sample contains 595 randomly selected cases of the 2,929 cases with final dispositions filed in federal court. While this sample is only 20 percent of all section 1983 suits brought against the NYPD between 2014 and 2019, as Table 2 shows, the cases in the analysis sample and full sample share similar percentages for case disposition, the presiding district court, and pro se plaintiffs. Median time to case disposition differed by two days and median settlement amount differed by $1,000 between the full dataset and the analysis sample.

It is possible that the sub-sample fails to represent the full sample on variables not indicated in the dataset. Factors specific to the parties, like sex and age of plaintiffs and defendants and factors specific to the case, like the nature of the claims and the presiding judge, are not observed in these data. Critically, there is no indicator of whether an officer has a prior misconduct record. But because the sample cases closely approximate the descriptive statistics from the full dataset, it appears to mirror key, known attributes of the full sample.[182]

The next sections present my qualitative and quantitative findings.

C. Textual Analysis

To understand what information parties to section 1983 suits naming NYPD officers as defendants seek to protect, I reviewed the text of forty-eight protective orders entered in cases within my analysis sample. While I identified 139 cases with protective orders in my analysis sample, the text of only forty-eight (35 percent) were available through publicly available sources. Taken together, each of the protective orders share striking similarities. Most judges signed the stipulated order without alteration or comment. The orders appear to modify the standard form presumptively issued in S.D.N.Y. cases governed by Local Rule 83.10(11).[183] Each explicitly protected personnel and disciplinary records.[184] Nearly all the orders prevent use beyond the purpose of the litigation and maintain the confidentiality of documents past the termination of the litigation. I describe: (1) if and how the orders describe the good cause standard and which rationales are offered; (2) how courts treat protective orders; (3) what information protective orders make confidential; (4) how information is protected; and (5) how the order describes the court’s power to modify and enforce protective orders.

1. Good Cause and Rationales

A textual analysis of the forty-eight proposed and granted protective orders shows that most orders recognized that good cause is the standard for entering protective orders under Rule 26(c). The majority, forty-one cases, followed the basic text of the Local Rule 83.10(11) and stated that “good cause” exists under “Rule 26(c)” for the court to enter a protective order.[185] Two orders justified the protective order with references to past agreement[186] and four simply provided justifications for the protective order without mentioning the standard.[187] Two court orders modifying the parties’ proposed protective order explained that “given the nature of the claims . . . certain documents produced in discovery may contain confidential private information for which special protection from public disclosure . . . would be warranted.”[188]

While most orders recognized good cause as the standard, most did not engage in a rigorous good cause analysis. FRCP 26(c) requires a judge to find good cause exists before entering a protective order.[189] Rule 26(c) broadly permits protective orders to “protect a party or person from annoyance, embarrassment, oppression, or undue burden or expense.”[190] But most of the cases did not justify the order on these grounds. Instead, thirty-five orders found the order should be entered because defendant-officers and the City of New York would not produce requested documents unless “appropriate protection for their confidentiality is assured.”[191] Nine cases expanded this rationale to include a statement that both defendants and plaintiffs’ request confidentiality protections.[192] These objections merely reflect a conclusory desire for protection and fail to provide any rationale for why good cause exists to grant the order.

Another common rationale, offered in sixteen cases, was that the defendant police officers and City of New York claimed that the information sought was privileged, including privileges for law enforcement and government.[193] In two cases, both parties[194] claimed privilege covered the documents. While privilege would certainly protect the information the privilege covers from disclosure, it is not the standard for a protective order. As discussed in Part IV.A, state law government and law enforcement privileges do not control federal courts.[195]

Ultimately, only one case adopted the language regarding confidentiality from Rule 83.10’s presumptive protective order. Both Rule 83.10 and the order in Jackson v. City of New York justified the order as satisfying good cause because “the parties seek to ensure that the confidentiality of these documents and information remains protected.”[196] This justification, resting only on party agreement, seems to violate the requirement that the court finds good cause even when parties agree, as previously discussed in Part I.A.[197]

Only one case offered a justification for good cause that seemed to satisfy the articulated good cause standard. The defendant officers in Marrero et al., v. City of New York asserted that disclosure of information to the plaintiffs “would impair the law enforcement operations and objectives of the NYPD” and “would impair the pending Civilian Complaint Review Board (“CCRB”) proceeding related to the underlying incident.”[198] Both stated rationales, particularized to the facts of the case, would likely satisfy Rule 26(c)’s good cause if such harm could be shown.

Table 1 summarizes the “good cause” rationales offered in these cases.

Note 198: Some orders offered multiple rationales, which explains why the total number of cases exceeds forty-eight.

2. Judicial Treatment of Protective Orders

Despite this perfunctory or entirely absent good cause analysis, only one case featured a denial of a protective order for lack of specificity. In Moore v. City of New York, Magistrate Judge Orenstein directed the City to “seek a more specifically targeted protective order during the discovery process,” and later granted the more specific order.[199] This trend is consistent across the full scope of cases in the analysis sample. In only three other cases did a judge partially grant a protective order (2.9 percent of cases). The court in the remaining 135 cases granted the requested protective order (97.1 percent of cases).

Instead of ensuring good cause exists for protective orders by analyzing the moving parties’ reasoning or finding good cause according to its discretion, many judges directed the parties to enter into protective orders at the outset of discovery. In Corbett v. City of New York, Judge Woods stated that “[t]he Court thanks the parties for working together to submit their proposed protective order for discovery in this case. The parties are directed to consult the Court’s Individual Rule 4.C and to submit a proposed protective order that complies with that rule.” [200] Judges in Avila v. City of New York, Freese v. Mattina, Ortiz v. City of New York, and Siemionko v. City of New York, et al. all directed the parties to draft a protective order as the cases proceeded to discovery.[201] Cases subject to S.D.N.Y.’s Rule 83.10 are presumed to accept the proposed protective order drafted by the court.[202] Some litigants subject to the rule did modify and ask for the court’s endorsements of other protective orders,[203] which S.D.N.Y. courts granted. But Rule 83.10 reflects a clear judicial preference for parties to conduct discovery without the court’s participation, which the court presumptively will enforce. The adoption of Rule 83.10 and the frequency of these directions in E.D.N.Y. cases suggest that judges often encourage parties to enter into stipulated protective orders.

3. Information Made Confidential by Protective Orders

Each order specifically protected certain information, nearly all of it focused on NYPD records and information pertaining to officers. Forty-five orders specifically protected NYPD officer’s personnel records and disciplinary records.[204] Forty-four orders protected investigations by the NYPD and the CCRB into officer conduct.[205] These protections reflect a frequent recognition that courts will grant orders covering this information because Rule 83.10 presumptively protects all personnel records, disciplinary records, and CCRB documents.[206]

But many orders went beyond the stock categories presumptively included in Rule 83.10. Eight orders specified that the materials the Internal Affairs Bureau produced were designated as confidential.[207] Four orders protected “performance evaluations”[208] and eight orders protected “NYPD training materials,” including the Patrol Guidelines, Administration Guide, Operation Orders, training manuals, directories, legal bulletins, and directives.[209] Three orders protected video that NYPD-issued cameras or a NYPD officer took.[210] Two orders included a catch-all provision that specifically protected “[a]ny other NYPD documents produced as a part of Monell discovery.”[211] Only six orders specifically protected private information like the officer’s telephone numbers, home addresses, social security numbers, birthdates, financial information, and tax records.[212]

The dialogue surrounding confidentiality focused squarely on officer records. Strikingly, only ten protective orders explicitly made any of the plaintiff’s records confidential. Seven orders provided protection for plaintiff’s medical or psychotherapy records.[213] Three orders protected both plaintiff and officer medical records.[214] Four orders protected officer’s medical records but not the plaintiff’s.[215] Only four orders protected files related to the plaintiffs’ arrests or criminal history.[216] The relative infrequency of protections for plaintiff’s medical and arrest records is noteworthy because the presumptive protective order under Rule 83.10 explicitly protects these types of documents.[217] This means that the moving party, typically the defendant-officer(s), affirmatively removed plaintiff-protective provisions from the standard order before seeking the court’s endorsement.

Further, nearly every order included a catch-all provision: by labeling a document confidential “in good faith,” parties could choose to protect any document not already protected. Seven orders followed the standard language from Rule 83.10, which allowed any party or the court to make such designations.[218] But thirty-three orders deviated from the presumptive order and narrowed the parties that could label discovery confidential to only the defendants or the court.[219]

Limiting the discretion to label discovery as confidential to only NYPD officers and City defendants gives these defendants discretion, not shared by the plaintiffs, to determine which types of documents must be kept secret. Only Magistrate Judge Go attempted to limit the broad power to make documents confidential in Linton v. City of New York by allowing parties to designate future items as confidential “only if the document is entitled to confidential treatment under applicable legal principles.”[220] But even this limitation still permits parties to define the scope of confidentiality through their interpretation of “applicable legal principles.”

Table 2 summarizes each of the categories of information these orders made confidential.

4. How Information Is Protected

Nearly every order specified how parties could use information and discovery covered by the protective order. Thirteen orders followed the text of Rule 83.10’s presumptive protective order, which limited either party’s use of the protected discovery to the evaluation, preparation, presentation or settlement related to the action.[221] But many more orders narrowed the permissible uses or the parties limited by the order. Fourteen orders stated that only plaintiffs and plaintiffs’ attorneys were bound by the use restrictions, although the permitted uses were again for evaluation, preparation, presentation, or settlement activities.[222] Further, fourteen orders limited plaintiffs’ and plaintiffs’ attorneys’ permissible use of covered discovery to only the preparation and presentation of the case [223] , and just one order limited both defendant’s and plaintiff’s attorneys to preparation and presentation uses.[224] Two orders imposed a more general bar on a plaintiff’s or plaintiff’s attorney’s ability to disclose confidential material.[225] The Linton and Fedd v. City of New York orders, entered by Magistrate Judge Go, were comparatively unique. Instead, these orders informed parties that it could not “be construed as conferring blanket protection on all disclosures or responses to discovery.”[226]

Several orders also included procedures to ensure that once litigation had concluded, neither party could use the protected discovery in the future. Nineteen orders required the plaintiff’s attorney to “destroy[]” or “return” to the defendants’ attorney all confidential material, including copies and notes, within thirty and sixty days of the case ending.[227] Rule 83.10 includes no such destruction provision. In Windley v. City of New York, Judge Scanlon modified this destruction requirement by hand to clarify that the court would retain a copy of any documents filed with the court regardless of whether the protective order covered them.[228]

Table 3 describes the use limitations included in these protective orders.

5. Courts' Powers to Modify and Enforce

Many of the orders included language that described the court’s powers to enforce and modify the orders. Twenty-two orders mimicked the language of Rule 83.10 on two points: the orders informed parties that the court both (1) retained jurisdiction to “enforce” obligations created under the order and “impose sanctions” for violating the order and (2) reserved its right to modify the orders in its discretion at any time.[229] But other orders deviated from this baseline. One order retained only a reference to the court’s right to modify,[230] and six only retained references to the court’s jurisdiction to enforce and issue sanctions.[231] Sixteen orders did not discuss the court’s powers at all.[232] In one stipulated protective order that failed to address the court’s powers, Judge Scanlon in Windley wrote that “the Court may modify this order at any time.”[233] Judge Scanlon also hand modified the scope of the order, striking out language that indicated that the “terms” of the order would be “binding upon . . . future parties.”[234] The orders in Linton and Fedd also reminded parties that the court would “revisit . . . this protective order . . . in light of the right of the public to inspect judicial documents.”[235] Removing references to the court’s powers to enforce and modify protective orders does not eliminate them.[236] But it could reveal how the parties wish to frame the agreement either as more or less susceptible to change or enforcement.

Table 4 summarizes how protective orders addressed the court’s powers.

The similarity in content and structure between all the orders tends to reflect the presumptive protective order issued under Rule 83.10 in S.D.N.Y. cases. But the modifications to the presumptive order show how important the City attorneys are in the protective order process and may reveal officers’ and the City’s priorities. Overall, protective orders tend to be more protective of individual officer’s files and NYPD records, while simultaneously being less protective of plaintiffs’ records than the Rule 83.10 order. The orders in my sample also tend to restrict only plaintiffs’ use of protected documents and give more discretion to officer and City defendants to label documents not already covered as confidential.

This document analysis shows that nearly every protective order in the sample protects police and NYPD records from public disclosure and attempts to keep these materials confidential indefinitely. It appears that these defendants value keeping NYPD employment, disciplinary, training, and policy materials confidential. The next section evaluates how the demonstrated preference for confidentiality in cases with protective orders may result in differences in settlement amount compared with cases that lack such confidentiality protections.

D. Quantitative Findings

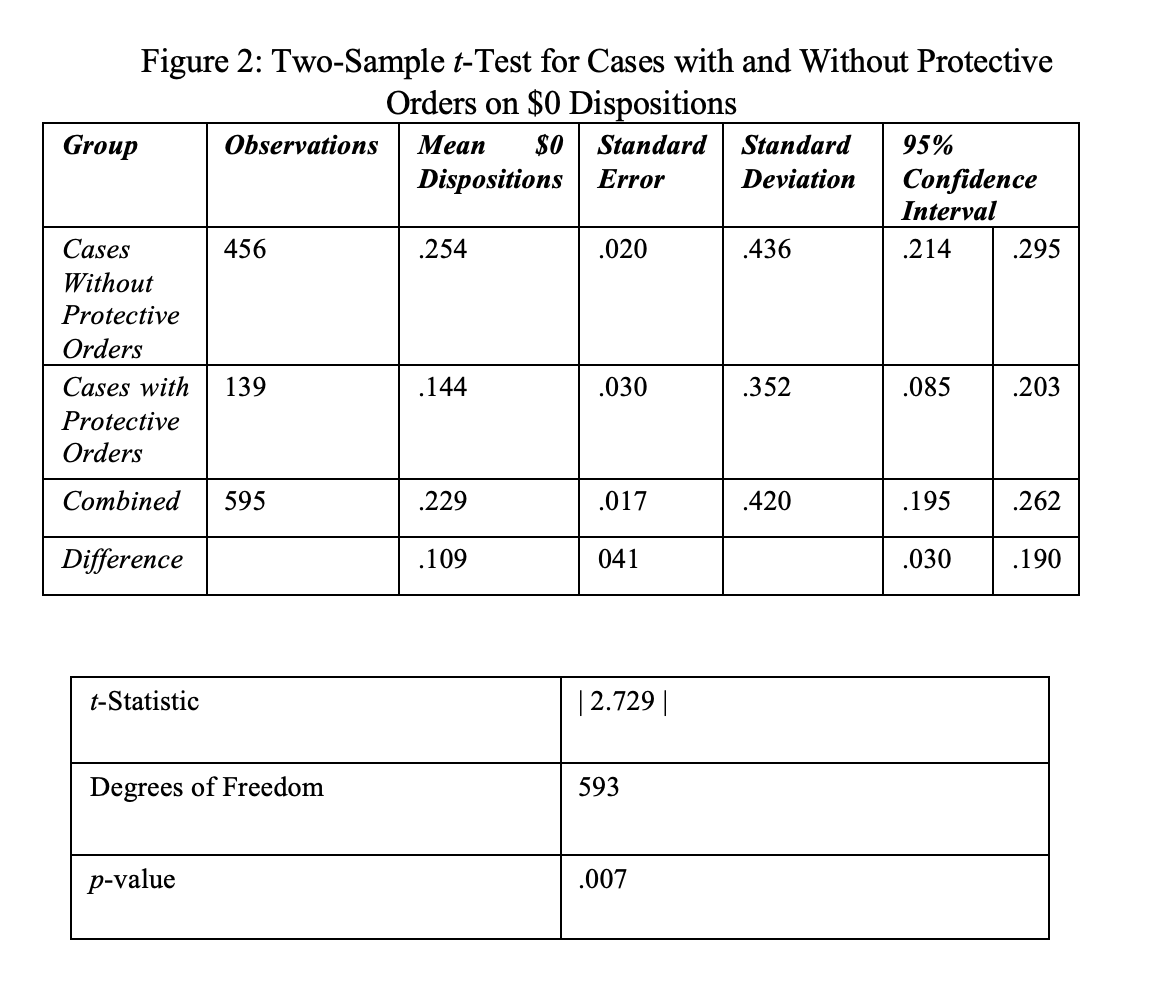

I conducted an independent samples t-test to test whether the difference between settlement values in cases with and without protective orders is statistically significant. My two-tailed independent samples t-test compares the difference in means of the settlement price for cases with and without protective orders. The test determines if the difference in the mean values is significantly different than zero.[237] A finding that the settlement prices are statistically significantly different at α=0.05 would mean that cases with protective orders can be distinguished from those without by considering the settlement amount.

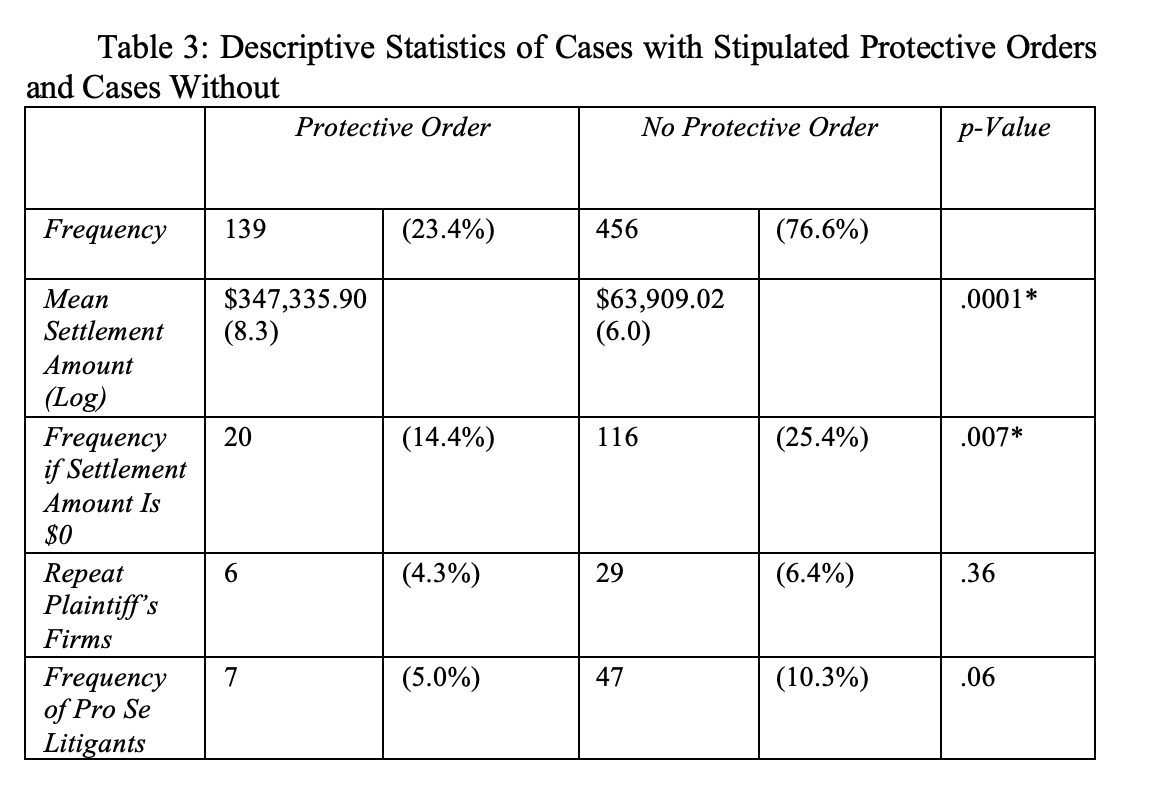

Considering the results of my t-test, I found that the 139 cases with protective orders (logged mean=8.3, standard deviation=5.5) compared to the 456 cases without protective orders (logged mean=6.0, standard deviation=6.3) settled for significantly different, and higher, settlement amounts, t(593)=3.9, p=0.0001. The p-value of 0.0001 means that if there is actually no difference in the mean settlement amounts between cases with and without protective orders, my observed result would be obtained in only 0.01% of analyses. Therefore, cases with protective orders are likely more expensive for NYPD Officers and NYC and more lucrative for plaintiffs.

Figure 1 describes the test.

E. Potential Mechanisms Driving the Qualitative and Quantitative Results

The results from both textual analysis of the protective orders and the t-test comparison of settlement amounts suggest that officers act strategically in moving for protective orders. There are several possible explanations for my findings. One inference the analyses may support is that when plaintiffs have a case against an officer with a potentially damaging personnel file, the City and its officers are willing to settle for a higher amount. Additionally, another explanation is that officers could request a protective order because they want to protect their privacy or prevent their past conduct from being linked to the current action even when they do not have frequent or dangerous misconduct. Perhaps City attorneys will move for a protective order whenever a plaintiff requests an officer’s employment records, suggesting that plaintiff’s attorneys influence the officers’ litigation behavior. Regardless of whether the misconduct records have damaging contents or not, the significant differences in mean settlement amount between the two types of cases suggest the NYPD strongly values protecting the confidentiality of records and potentially being willing to pay more to do so.

Alternative explanations that explain the higher settlement amounts in cases with protective orders without considering confidentiality rationales also have support in the data. Cases with stipulated protective orders may have egregious facts, extensive injuries, or more aggressive or experienced plaintiff’s attorneys that serve as the primary drivers of higher settlement amounts. The following considers each alternative explanation.

Merits of the Case: While the data does not provide details on the case facts, the comparative numbers of cases in each group that settled for $0 could serve as a proxy on the merits of the plaintiff’s case. Comparing the two, twenty of the 139 cases with protective orders (14.4 percent) settled for $0, while a more substantial 116 of the 456 cases without protective orders (25.4 percent) settled for $0. After assigning a value of one to cases with $0 dispositions and a value of zero to cases with higher settlement amounts, I compared the difference in means between cases with and without protective orders on this variable using a two-tailed independent-means test. The test shows that this difference is statistically different from zero with t(593)=2.7 and p=.007. Figure 2 describes the test.

The fact that cases without protective orders are more likely to settle for $0 does not cut against the inference that valuing record confidentiality influences officers’ willingness to settle for higher amounts. These findings also support the theory that the City and NYPD act strategically to protect confidentiality. If a $0 disposition signals a weak case, this finding could suggest that NYPD officers may care more about keeping their records confidential when they are defendants in a case that credibly charges them with misconduct. It could also signal that officers with past misconduct histories who need protection are more likely to face future litigation that have a higher chance of success on the merits. Together, the statistical findings that cases with protective orders settle for higher amounts than those without and are less likely to be settled for $0 correlate with the possibility that NYPD officers seek to keep police misconduct records confidential when a plaintiff’s case is strong.