He Said. She Said. The iPhone Said. The Use of Secret Recordings in Domestic Violence Litigation

Trigger Warning: This Note describes graphic scenes of domestic violence. It also discusses child abuse, elder abuse, and sexual assault.

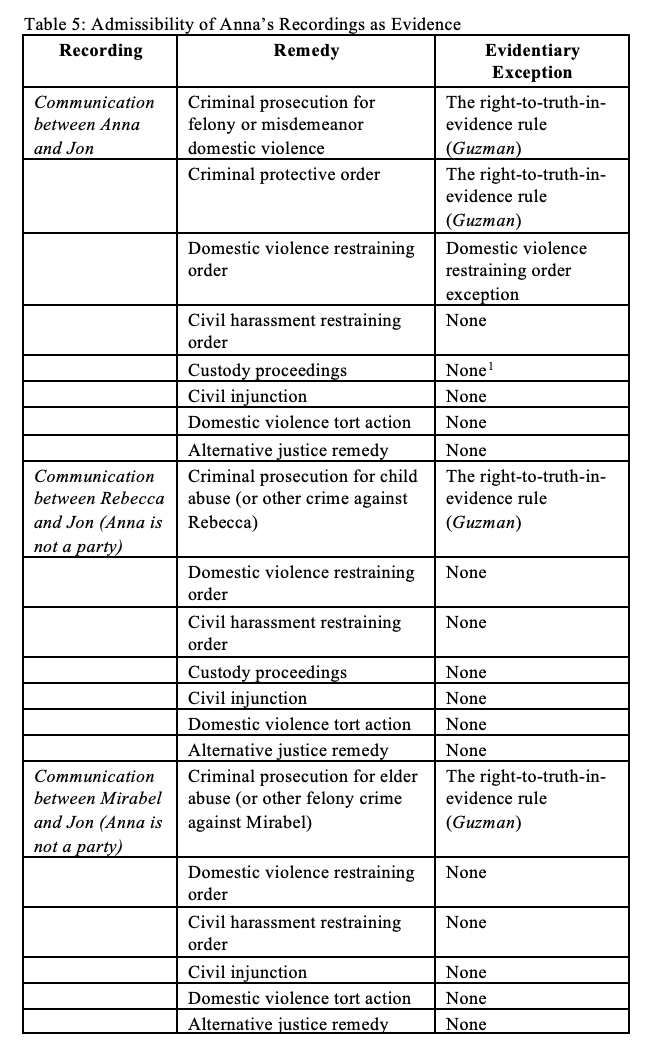

This Note explores the use of secret recordings in domestic violence litigation. It is particularly concerned with how the criminalization of domestic violence influences the laws governing the creation and use of secret recordings in this context. Secret recordings can provide determinative evidence of domestic violence. However, a domestic violence survivor who makes a secret recording is criminally and civilly liable under California’s Anti-Eavesdropping Statute (CEPA). CEPA also renders secret recordings inadmissible as evidence. Although the “Right to Truth-in-Evidence” provision of Proposition 8 abrogates CEPA for purposes of admitting secret recordings for criminal prosecutions, there is no equivalent rule for civil and family court litigation. The only statutory exceptions to CEPA that apply to domestic violence are narrow in scope and do not legalize secret recordings for use in noncriminal settings. CEPA encourages dependence on criminal remedies and denies domestic violence survivors the ability to effectively pursue the remedy of their choice. This Note proposes statutory exceptions to CEPA that would protect domestic violence survivors from liability and enable them to use secret recordings to secure civil law, family law, and alternative justice remedies as well as, or instead of, criminal remedies.

Table of Contents Show

Introduction

In the spring of 2017, the public was outraged after watching a viral recording of a Silicon Valley CEO beating his wife, a software engineer at Apple. His wife, Neha Rastogi, had secretly recorded the video, which captured Abhishek Gattani brutally berating and beating Rastogi.[2] Rastogi’s secret recording was admitted as evidence, and Gattani pleaded no-contest to misdemeanor offensive touching and felony accessory after the fact.[3] Prior to his conviction, Gattani had been abusing his wife for a decade—since shortly after their marriage.[4] Rastogi believed that Gattani would soon kill her.[5]

Rastogi’s secret recordings were critical to her case. Indeed, The Daily Beast referred to Rastogi’s story as “the case of she-and-the-iPhone said.”[6] Rastogi’s first recording started with her saying, “Repeat what you were saying, what were you saying?”[7] Gattani responded that he was going to make her resign from her job, even if he had to push her around all day, and that he wanted to see her burn.[8] On May 17, 2017, Rastogi filmed the now widely-shared video, where one can hear Gattani berating Rastogi as he hit her nine times.[9] In another recording, Rastogi asked, “What did you just say? You want to kill me basically?”[10] He responded that he would like to see her murdered.[11] In her victim impact statement, Rastogi described the importance of these recordings to her case:

This time around there is evidence in the form of audio and video clips which clearly show and prove that Abhishek was hitting me . . . there are videos of him threatening to stab me 45 times and many of these videos show this abuse towards and happening in the presence of our then 2.5 year old child . . . There is also evidence of his parents confirming (over a video recording) to his physical abuse against them (both father and mother) as well as Abhishek’s younger sister.[12]

Even with these recordings, Gattani was only sentenced to fifteen days in jail.

The same themes—domestic violence and secret recordings—were present in the story of Tiawanda Moore, as recounted by Professor Beth E. Richie.[13] Yet that story had a very different ending. Moore called the police after her boyfriend assaulted her.[14] The police arrived and separated Moore from her boyfriend.[15] One of the officers then proceeded to proposition Moore and ask for her phone number.[16] Moore filed a complaint, and ultimately secretly recorded a conversation of the officers’ disturbing responses to her complaint.[17] Unfortunately, making a secret recording violated an anti-eavesdropping law, and so the officers retaliated against Moore with criminal charges.[18] Thus, Moore went from suffering domestic violence to suffering violence by the state.[19]

The stories of Rastogi and Moore reveal several complicated dynamics of obtaining domestic violence remedies. First, their stories reveal that domestic violence and other gender-based crimes (such as the sexual harassment in Moore’s story) are incredibly difficult to prove. Second, their stories reveal that secret recordings can provide evidence that is absolutely critical to proving domestic violence and gender-based crimes to both a judge and to one’s community. Third, their stories reveal that criminal remedies can be inadequate. It is inconceivable that Gattani would be rehabilitated from a decade-long history of domestic violence after a fifteen-day stay in a jail where he was unlikely to get any sort of psychological counseling. Fourth, their stories reveal that criminal remedies can be dangerous—Moore’s call to the police ended up with her being harassed and, ultimately, criminally charged. And, finally, their stories reveal that making a secret recording can open one up to serious criminal liability and repercussions.

This Note explores the use of secret recordings in domestic violence litigation. Part I identifies certain tensions between aspects of the criminal justice reform movement—such as calls to defund or abolish police and prisons—and the anti-domestic violence movement’s dedication to criminalization as the primary remedy against domestic violence. Part II discusses the merits and limitations of criminal law, civil law, family law, and alternative justice remedies to domestic violence in California. Part III explains why secret recordings are uniquely crucial to a survivor’s ability to prove domestic violence and obtain a remedy. Part IV argues that California’s Anti-Eavesdropping Statute (CEPA) exposes domestic violence survivors to criminal and civil liability and makes it nearly impossible for a survivor to obtain noncriminal remedies if their case turns on the admissibility of a secret recording. Part IV also identifies exceptions and strategies for circumventing CEPA in this context. Part V proposes new statutory exceptions that would protect survivors from CEPA liability and make secret recordings admissible for domestic violence proceedings in civil and family court. Throughout this Note, I will use a hypothetical family (“Anna and Jon”) as a vehicle to help readers understand the available domestic violence remedies, the importance of secret recordings, and the impact of anti-eavesdropping laws on the ability of survivors to use secret recordings to obtain remedies.

Ultimately, this Note seeks to reveal some of the collateral effects of CEPA on the criminal justice system, the penal state, and a domestic violence survivor’s ability to pursue the solution of their choice. I make three main arguments: (1) the combined effects of CEPA and the truth-in-evidence rule encourage reliance on criminal domestic violence remedies at the expense of noncriminal remedies; (2) this limits a domestic violence survivor’s ability to choose the remedy—be it criminal, family, civil, or extralegal—that works best for the survivor and their family; and (3) California should pass legislation that protects domestic violence survivors from CEPA liability and empowers them to pursue civil, family, and alternative justice remedies as well as, or instead of, criminal remedies.

Finally, a brief note on terminology. There have been many debates among the people who experience domestic violence about whether they should be referred to as “survivors” or “victims.”[20] This Note has opted to use the term “survivor” rather than “victim” wherever possible. However, in certain places, I use the word victim because the person at issue did not survive the domestic violence, or because the word victim is used in the statute or case law at issue. In addition, this Note uses a hypothetical family in order to illustrate how the current laws impact a survivor’s ability to obtain a legal remedy. In this hypothetical, the person experiencing domestic violence is a woman and the perpetrator is a man, in recognition of the fact that domestic violence remains a gendered crime: women are predominantly the survivors and victims of domestic violence, and men are predominantly the perpetrators.[21] However, domestic violence is nonbinary. It impacts people of all gender identities, including many people in the LGBTQ+ community.[22]

I. The Relationship Between State Violence and Domestic Violence

This Section explains how the criminalization of domestic violence resulted in the limited remedies that are available to survivors today. This context is important because it explains why there are currently so few noncriminal remedies available to people experiencing domestic violence. Moreover, it gives context as to why the current domestic violence exceptions to CEPA are almost exclusively only available in criminal court. The purpose of this Section is to provide some background as to why lawmakers need to think beyond criminal remedies when they create legal remedies for domestic violence survivors.

Part I.A explains some of the similarities and contradictions between the anti-domestic violence movement and the prison abolition movement, both of which emerged from the progressive left. Part I.B recounts how the anti-domestic violence movement became so dependent on criminal remedies in the first place. Part I.C explains some of the major criticisms of the criminalization of domestic violence and describes alternative, feminist abolitionist approaches to ending domestic violence. Finally, Part I.D argues that any proposed remedy to domestic violence should neither focus exclusively on criminal remedies nor ignore the reality that—at least for the time being—criminal remedies will sometimes be necessary in a subset of cases. This Note trusts the individual survivor to determine what type of remedy is best for the survivor and their family.

A. Background

The movements to combat state violence and gender-based violence—reiterated most recently in the Black Lives Matter and #MeToo movements—share common origins. First, each movement seeks to address a type of systemic violence against a marginalized group. Historically speaking, gender violence and state violence against people of color share many characteristics. This violence occurs because (1) each marginalized group—Black people, women, and particularly Black women—have been systematically denied dominion over their own bodies, and (2) because law enforcement and the legal system have historically ignored or actively contributed to violence against these marginalized groups.[23] Indeed, Angela Harris noted that it is not always possible to distinguish between domestic violence and state violence.[24] Historically, society approved of the right of husbands to mete out the equivalent of state-inflicted corporal punishment on their wives—even to the point of using state instruments of torture.[25] In fact, prison was originally imagined as an alternative to state-inflicted corporal and capital punishment.[26] Yet even as prisons replaced some of the most violent forms of corporal punishment, little was done to protect the people who were subjected to corporal punishment in their own homes.[27] In sum, domestic violence and state violence share common goals of punishing marginalized groups and have historically been enabled by the same structures.

Second, the Black Lives Matter and anti-domestic violence movements took so long to gain popular traction because the general public simply did not believe the accounts of such violence from survivors and witnesses. In other words, the public did not believe the accounts of police violence towards Black people and gender violence towards women and gender nonconforming people because these accounts were coming from Black people, women, and gender nonconforming people. Because of this, recordings and other forms of tangible evidence have played a critical role in changing public opinion about the prevalence of racist police violence and domestic violence. Although police have long terrorized communities of color, many White and privileged communities did not believe or understand the extent of the problem until they saw video recordings of police brutality. Indeed, it is very likely that there would not have been nearly so much support for the Black Lives Matter protests of the summer of 2020 without the video recording of the murder of George Floyd. Similarly, there was little recognition of the pervasiveness of domestic violence in the United States until the anti-domestic violence movement launched a targeted campaign featuring first-person accounts of domestic violence in the 1980s, as described in the following Section. Moreover, many survivors of domestic violence and gender violence have only been believed after they were able to produce recordings or photographic evidence, as described in Part III. Thus, both movements have suffered from systemic disbelief, and recordings and other tangible forms of evidence have been crucial in overcoming that disbelief.

Despite their shared origins, each movement has respectively demanded a very different remedy for addressing such violence. In the summer of 2020, the horrific police murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor forced the nation—or at least segments of it—to acknowledge what disenfranchised communities of color have always known: that American police and carceral systems are deeply racist, violent, and overly punitive. In response, the Black Lives Matter movement gained widespread support among the American people, corporations, sports teams, and the Democratic party.[28] Many of the Black Lives Matter protesters advocated for defunding the police and prison abolition.[29] While these concepts have been touted in progressive circles for decades, this was arguably the first time that the press, popular figures, and even members of the general populace started to treat these ideas with any degree of seriousness.[30] Of course, there is nuance and disagreement within the movement: while the Black Lives Matter movement is fundamentally about defunding the police and abolishing the carceral state, many activists still expect justice to be meted out within the criminal justice system—as demonstrated by the demand for criminal convictions for police brutality.[31] Yet even while progressives demanded a reduction in American policing and incarceration, 2020 witnessed an equally loud progressive demand for certain forms of violence to be pursued and punished more seriously. A few months before the Black Lives Matter protests kicked off in the summer of 2020, Harvey Weinstein was sentenced to twenty-three years in prison for rape and sexual assault after a monthlong trial.[32] For many, this was a fitting resolution for the serial rapist who had been outed by Ronan Farrow in 2017,[33] triggering the #MeToo movement[34] that forced the nation to reckon with systemic sexual harassment and assault. While many prominent voices in the #MeToo movement have advocated for alternative forms of justice rather than increased criminalization,[35] there have undeniably been criminalization components to #MeToo as well: the #MeToo movement has resulted in calls for more expansive criminal sexual assault laws,[36] seven criminal convictions and five criminal charges,[37] and the recall of the judge who sentenced the infinitely privileged rapist Brock Turner to a mere six months in jail.[38] Thus, while neither movement is exclusively pro- or anti-criminalization, the primary remedy that the Black Lives Matter and gender justice movements demand is noticeably different. There have been moments of tension between progressive calls to reduce or eliminate the use of jails and prisons to punish, and on the other hand, calls to punish the perpetrators of gender violence by putting them in jails or prison.[39]

I am in no way arguing that defunding the police and prison abolition movements are incompatible with the #MeToo movement and gender justice movements generally. Indeed, I believe that these movements can, and should, be mutually reinforcing. Rather, I seek to highlight some of the tensions that many progressives have grappled with even as they passionately support both movements: how do we demand that perpetrators of domestic violence be held accountable while also demanding the reduction—or elimination—of police and incarceration? How do we ask society to believe survivors that have been sexually assaulted or harassed while also acknowledging that society used fabricated claims of sexual assault and harassment of White women to justify inflicting legal[40] and extralegal brutality against Black men?[41] How do we reconcile demands that sexual assaulters and women-beaters be banished from society with ideas of restorative justice and rehabilitation? Is it possible to end domestic violence without imposing the violence of the carceral state?

Before this Note can delve into these tensions, it is first necessary to summarize how the mainstream anti-domestic violence movement increased criminalization and empowered the prison state.

B. The Criminalization of Domestic Violence

This Section explains how the anti-domestic violence movement became so enmeshed with the criminal justice system. Although domestic violence has surely been around since the dawn of time,[42] only in the last fifty years has domestic violence been viewed as a legitimate societal wrong warranting state intervention. As Angela Davis explained in her 2000 keynote speech at the Color of Violence Conference:

Many of us now take for granted that misogynist violence is a legitimate political issue, but let us remember that a little more than two decades ago, most people considered “domestic violence” to be a private concern and thus not a proper subject of public discourse or political intervention. Only one generation separates us from that era of silence.[43]

Indeed, the full extent of domestic violence first came out publicly during the women’s liberation movement in the 1960s.[44] Perhaps more notably, domestic violence advocates of that era also revealed that police and prosecutors were systematically ignoring domestic violence and refusing to arrest and charge perpetrators.[45] In the late 1970s, twelve “battered wives” sued clerks of the Family Court of New York City and an official of the New York City Department of Probation for systematically acting to prevent and dissuade these women from accessing legal remedies to domestic violence, such as protection orders.[46]

As it became increasingly clear that the state, courts, and law enforcement had routinely ignored domestic violence, “a sense of moral outrage took over.”[47] It was this “sense that violence against women is not taken seriously in our heteropatriarchal society” that “motivated feminists to ally with the criminal justice system.”[48] Starting in the late 1970s, feminists fought to force these actors to treat domestic violence as they would any other crime.[49] Arguably, second-wave feminists took it even further than that. I will briefly explain some of their most significant reforms:

Mandatory Arrest. In the early 1980s, a group of sociologists published the results from the Minneapolis Domestic Violence Experiment, which found that arresting domestic violence perpetrators was the most effective means of deterring future domestic violence.[50] This study became highly influential among police departments[51] and in the mainstream anti-domestic violence movement, which started lobbying vigorously for mandatory arrest and pro-arrest policies.[52] The idea behind such policies was that police could not be trusted to treat domestic violence like a real crime, and thus must be required to make arrests without room for discretion.[53] Such policies were revolutionary because officers normally could not perform a warrantless arrest for a misdemeanor that was committed outside the presence of an officer.[54] This lobbying was successful: in 1984, only 10 percent of police departments had pro-arrest policies for domestic violence, but by 1989, 89 percent of police departments had such policies.[55] Today, every state has either a pro-arrest or mandatory arrest policy for cases involving domestic violence.[56] Many scholars and advocates have continued to push for such policies wherever police are called to address domestic violence.[57]

No-Drop Prosecutions. No-drop prosecutions emerged for the same reason as mandatory arrest policies: domestic violence advocates did not trust prosecutors to treat domestic violence like a real crime. In turn, many prosecutors blamed their failure to pursue such cases on the fact that many survivors of domestic violence refused to testify.[58] A no-drop policy meant that “prosecutors would not dismiss criminal charges in otherwise winnable cases simply because the victim was not interested in, or even adamantly opposed to, pursuing the case.”[59] Today, in certain jurisdictions, this means that prosecutors can compel unwilling survivors to testify by subpoena, by issuing a warrant, or even by arresting the survivor.[60]

Special Evidentiary Rules. Legislatures passed various special evidentiary rules designed to make it easier to prosecute gender crimes, including domestic violence. Three examples of these special evidentiary rules include the “Rape Shield Laws,” California Evidence Code Section 1109, and California Evidence Code Section 1370. “Rape Shield Laws” prohibit the defense from using evidence about the survivor and their past sexual behavior as evidence that they consented to sex during the alleged sexual assault.[61] Lisa Marie De Sanctis wrote and convinced the legislature to pass California Evidence Code section 1109, which allows previously inadmissible propensity evidence into domestic violence prosecutions.[62] This means that prosecutors can show evidence that a defendant committed domestic violence in the past in order to prove that they are guilty of this particular incident of domestic violence—an argument that is prohibited for almost every other crime.[63] After Nicole Brown Simpson’s diary entries detailing the domestic violence she had suffered at the hands of O.J. Simpson were excluded as hearsay in Simpson’s criminal trial, the California legislature enacted California Evidence Code section 1370, which creates a limited hearsay exception for domestic violence cases.[64]

VAWA. One of the biggest legacies of this era was the federal Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) of 1994. The primary goal of this Act was to heighten criminal justice responses to violence against women.[65] The secondary goal was to fund survivor services.[66] VAWA allocated millions of dollars to support courts, police, and prosecutors pursuing domestic violence cases.[67] In addition, VAWA also created monetary incentives to convince domestic violence advocates to work with police and prosecutors.[68] Multiple scholars have pointed out that these monetary incentives played a huge role in shaping the partnership between the mainstream domestic violence movement and law enforcement.[69] For example, part of VAWA funding was contingent on the state adopting a pro- or mandatory arrest policy for cases involving domestic violence.[70] Indeed, VAWA was part of the Omnibus Crime Bill of 1994, which played an infamous role in criminalization and mass incarceration.

In sum, the mainstream domestic violence movement of the 70s and 80s made great strides in convincing the public to take domestic violence seriously. It also contributed to important noncriminal responses to domestic violence: the first shelters for battered women emerged in the 1970s, as did the first national organization to end violence against women.[71] But ultimately, this wave of feminism has been remembered “for its contributions to policing, prosecution, and punishment.”[72]

C. The Feminist Abolitionist Approach to Addressing Domestic Violence

This Section will summarize the feminist abolitionist approach to solving domestic violence. The feminist abolitionist movement emerged simultaneously with the mainstream criminalization movement of the 1970s, but the latter movement attracted more popular support. In recent years, the feminist abolitionist approach has gained more traction as people have recognized the repercussions of the criminalization era. Feminist abolitionists make three primary arguments regarding domestic violence: (1) criminalization does not improve outcomes for survivors, (2) criminalization increases domestic violence on a societal level because criminal remedies are inherently violent and do not resolve the underlying issues that cause domestic violence, and thus (3) anti-domestic violence advocates should advocate for prison abolition in order to truly end domestic violence. I will evaluate each argument in turn.

1. Criminalization Does Not Always Make Survivors Safer

This Section discusses criticisms of the movement to criminalize domestic violence. It concludes that while criminalization can benefit privileged survivors—such as White, married women—it can cause oppressed and marginalized survivors—such as people of color and undocumented people—to suffer even worse and more frequent violence.

As the mainstream domestic violence movement became increasingly entwined with law enforcement, feminist abolitionists, most of them women of color, spoke up against what they saw as an unholy alliance. Women of color have been active in domestic violence advocacy since its inception.[73] At this inception, the movement was not grounded in criminal responses but focused primarily on community-based interventions and providing economic, social, and psychological support to survivors. Yet, as Beth E. Richie explained, the rhetoric and blind spots of the mainstream anti-violence movement made it the perfect conduit for the prison state:

There was a moment, I do not know if it was like fifteen minutes or maybe it was fifteen years, where our rhetoric, our resources, our approaches, our relationships with the criminal legal system meant that we were ripe for being taken advantage of by the forces that were building up a prison nation. In other words, they used us. They took our words, they took our work, they took our people, they took our money and said, “You girls doing your anti-violence work are right, it is a crime, and we have got something for that.” There was really a moment where we said “cool, take it.” Some of us said, “don’t go there,” but the train had already left the station.[74]

How did the mainstream movement become so entwined with law enforcement? Or, as Aya Gruber put it, “[h]ow were feminist lawyers so successful at making the remarkably broad claim that every woman benefited from arrest?”[75] The answer is that the anti-domestic violence movement was racist in many respects.[76] In particular, the movement was blind to how race and class affect how people are impacted by domestic violence.[77] Richie recounted attending her first conference sponsored by the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence and resonating with the analysis of gender and inequality but being disappointed in the movement’s failure to incorporate issues of race, class, and equality.[78] The theme of this initial movement was that domestic violence “could happen to anyone.”[79] In reality, this meant that “the ‘ones’ with the most visibility, the most power, and the most public sympathy [were] the ‘ones’ whose needs [were] taken most seriously.”[80] The prototypical domestic violence survivor became the White housewife being beaten by her husband, not, for example, the Black teenage survivor of sex trafficking.[81] Because the movement was centered around finding solutions for the White housewife, it did not come up with solutions for women with less power.[82] Instead, it focused on criminalization. But, as Leigh Goodmark explained, “[c]riminalization most benefits those who feel safer as a result of interventions but are immune from most of its costs: people who don’t share children with their partners, people who are no longer in relationships with those partners, people who don’t rely on their partners in any way, higher-income people.”[83] In other words, the mainstream anti-violence movement focused on criminalization because this movement centered the needs of White women, and failed to account for how race, class, and other axes of disenfranchisement impact how people experience domestic violence.

As the criminalization of domestic violence progressed, many scholars and advocates pushed back against its deleterious effects on marginalized communities, including many survivors of domestic violence.[84] Feminist abolitionists noted that the mainstream movement’s obsession with criminalization actually increased the risk of domestic violence to women of color.[85] Perhaps the most glaring example of this is the ideological demise of mandatory arrest policies.[86] In 2015, Lawrence W. Sherman, father of the mandatory arrest, recanted his previous recommendations after conducting a new experiment that found that domestic violence victims were 64 percent more likely to have died of all causes if their abusers were arrested and jailed than if they were warned and allowed to stay home.[87] These numbers were even more stark when race was considered: arrest increased mortality rates for White victims by 9 percent, but increased mortality for Black victims by 98 percent.[88] Increased criminalization also increased the arrests and imprisonments of survivors of domestic violence.[89] After seeing the impact of these policies, Sherman now advocates for restorative justice.[90]

Advocates have pointed out that for many women of color, police are themselves perpetrators of violence, rather than the intervening force that the mainstream domestic violence movement imagined them to be.[91] Thus, the failure to focus on noncriminal remedies to domestic violence means that many domestic violence survivors who are unable or unwilling to involve the police simply have no one to turn to.

2. Over-criminalization Makes Society More Dangerous

This Section discusses how two aspects of criminalization—incarceration and policing—affect domestic violence rates on a societal level.

Feminist abolitionists have argued that because prisons are dangerous places where gender violence is endemic, reliance on the prison system “in the long run perpetuates more gender violence—directed particularly at the most vulnerable and disenfranchised communities.”[92] Feminist abolitionists acknowledge that state violence and gender violence are often mutually reinforcing. Angela Davis has questioned whether reliance on the criminal justice system to fix domestic violence has done more harm than good.[93]

Abolitionists have long argued that prisons make society more dangerous. The United States imprisons more people for lengthier sentences and has the highest incarceration rates of any other country.[94] In large part, this is because prisons are the opposite of rehabilitative: they are dangerous, violent,[95] and rife with sexual abuse.[96] Additionally, incarcerated people are frequently unable to access adequate healthcare, particularly mental healthcare—a system failure that is completely inconsistent with rehabilitation.[97] Aside from the violence and trauma incarcerated people are subjected to while incarcerated, incarceration also has a detrimental effect on families because it strains familial bonds between parents that are incarcerated and their children.[98] In sum, the efficacy of incarceration in reducing crime has not been proven.[99]

Policing, too, frequently detracts from public safety and increases violence.[100] The amount of money we spend on policing and incarceration diverts funds[101] that could be better spent on education, access to healthcare, mental health and drug treatment, and general development and investment in communities.[102]

Finally, American imprisonment and policing systems are deeply racist, and have an enormously disparate impact on communities of color.[103]

As of today, evidence on whether increased criminalization has effectively reduced domestic violence is inconclusive.[104] What is clear, however, is that the increase in criminalization has made the world decidedly less safe for disenfranchised women and has had an indeterminable impact on domestic violence as a whole. Thus, feminist abolitionists have argued that the mainstream anti-violence movement’s marriage with criminalization was a mistake, and that prison should generally be seen as an exacerbator of, rather than a remedy to, domestic violence.

3. State Violence Will Not End Domestic Violence

Feminist abolitionist scholars have grappled with the tension between balancing the need to end gender violence with the need to end the violence of the carceral state. Davis explained this dilemma perfectly:

I should say that this is one of the most vexing issues confronting feminists today. On the one hand, it is necessary to create legal remedies for women who are survivors of violence. But on the other hand, when the remedies rely on punishment within institutions that further promote violence–against women and men, how do we work with this contradiction?[105]

Yet ending both state violence and domestic violence can be mutually reinforcing goals. Indeed, many scholars have advocated for prison abolition as a remedy to domestic violence. While prison abolition means different things to different people,[106] it can be broadly understood as the process of replacing incarceration with a combination of alternative remedies based on improving quality of life, empowering communities, and focusing on reparation and reconciliation rather than punishment for punishment’s sake.[107] Many have argued that rehabilitation is actually a more effective means of protecting the community than incarceration.[108] At their core, calls to abolish prisons and defund the police are about “demanding that the state divest from policing and imprisonment and invest in new forms of more equitable and just existence.”[109]

Angela P. Harris has called for a new analysis that “furthers neither the conservative project of sequestering millions of men of color in accordance with the contemporary dictates of globalized capital and its prison industrial complex, nor the equally conservative project of abandoning poor women of color to a continuum of violence that extends from the sweatshops through the prisons, to shelters, and into bedrooms at home.”[110] Many feminist abolitionist scholars have argued that moving towards decriminalization would be a more effective means of ending domestic violence.[111] As an alternative to the criminal justice system, Goodmark envisioned overlapping measures such as providing economic resources to survivors,[112] providing safe and affordable housing, gun control laws, public health programs that address mental health—particularly past trauma—of perpetrators, community accountability programs, and restorative justice.[113] In sum, feminist abolitionists have argued that noncriminal approaches would be more effective overall at ending domestic violence than defaulting to the penal state to end domestic violence.

As we work towards the dual progressive goals of ending state violence and domestic violence, no domestic violence remedy should be proposed without first evaluating how it will affect other marginalized groups, particularly communities of color. Moreover, I urge practitioners in the domestic violence field to invest more in noncriminal remedies to domestic violence and resist the urge to center police and prosecutors as the end-all be-all solution to domestic violence.

D. Empowering the Survivor

Although the mainstream anti-domestic violence movement has gone too far in promoting domestic violence exceptionalism,[114] it must also be acknowledged that domestic violence does present unique challenges.[115] Domestic violence can involve physical, psychological, and sexual abuse, as well as physical, psychological, financial, and legal entrapment.[116] Domestic violence can be all-encompassing to a victim in ways that an isolated incident of a more “typical” crime is not.[117] Moreover, chronic batterers pursue their victims with a dedication that is rarely seen in other crimes: globally, fifty thousand women are murdered each year by intimate partners and family members.[118] Between 2015 and 2020, nearly half of the transgender women who were murdered were killed by their intimate partners.[119] It is well documented that the most dangerous time for domestic violence victims and survivors is when they attempt to leave their abusers.[120] Abolitionists have discussed the possibility that even in a post-carceral world, prison—or some humane form of societal separation—may exist on the “margins.” I would not be surprised if these hypothetical margins ended up including the worst of domestic violence batterers.

In discussing injustices, progressives frequently focus on creating solutions that center the people suffering from the most axes of marginalization and disenfranchisement. The idea is that a solution that lifts up the people in the worst positions will lift everyone up. However, in domestic violence, this approach can produce vastly different outcomes depending on who you center. For example, the conversation could focus on an undocumented woman, living in extreme poverty with her four children, who is assaulted once by the children’s father, who is also undocumented. Assuming she does not want to risk the father of her children being deported, the best remedy for that woman may well be stable housing, money, and counseling. On the other hand, if the conversation focuses on a woman experiencing extreme, systematic violence at the hands of her husband—who happens to be a cop—the only solution may be incarceration because that may be the only realistic way to prevent him from murdering her in our current system. Thus, when discussing domestic violence remedies, we must simultaneously center both the people who suffer the most extreme forms of violence and oppression at the hands of the state and the people who suffer the most extreme forms of violence at the hands of their partners.

Of course, all of this requires acknowledging that domestic violence exists on a spectrum of harm, and while all domestic violence is unacceptable, different types of harm will require different solutions, responses, and interventions. This Note does not attempt to prescribe these different remedies. Instead, I presume that the survivor is the person best situated to determine which existing remedy is likely to work for them given their specific circumstances.

In the next Section, I will summarize the available criminal, civil, family, and alternative justice remedies to domestic violence in California. I will then discuss the benefits and drawbacks of each potential remedy for an individual who seeks to safely leave their abuser.

II. Domestic Violence Remedies

This Section will explain some of the myriad challenges that prevent domestic violence survivors and victims from successfully leaving their batterers, and the remedies available to people experiencing domestic violence in California. I will use an imaginary family to illustrate how the statutory provisions at issue affect the ability of domestic violence victims to secure aid through the California legal system. I will refer to these hypothetical family members by name to humanize the people who are impacted by domestic violence, and to avoid loaded words such as “victim,” “survivor,” and “batterer.” First, I will outline the hypothetical situation facing this family, and then I will describe the legal remedies available to this family in California.

The Family

Anna has been married to her husband, Jon, for five years. They live in a small town in Northern California. Anna and Jon have a daughter together named Rebecca, who has just turned two. Anna works full time as a sales associate at a retail store. Jon works sporadically at various construction jobs, mostly for cash. Jon’s mother, Mirabel, also lives with them. Mirabel is in the advanced stages of dementia and is nonverbal. Anna’s parents are deceased, and she has no extended family in the area. Jon has a small gun collection.[121]

Jon started to become abusive towards Anna when he lost his job a few months after their wedding. At first, the violence was infrequent and usually limited to slapping or pushing. But it gradually escalated in both frequency and intensity. A few weeks ago, he punched Anna so hard that she fell unconscious. He has also strangled her on several occasions, and frequently forces her to have sex with him.

Anna has not told anyone in her community about the abuse because she does not think anyone will believe her. This is partly because Jon has routinely told her that no one will believe her. Jon is also very well liked. He is routinely involved in their church and is a popular member of a recreational baseball team. He is charismatic, funny, and always the life of the party. Anna is shy, socially awkward, and has very few close friends. Since marrying Jon, she has lost most of her friends because Jon has been steadily isolating her. At this point, Anna is truly convinced that no one in her community will believe that Jon abuses her without proof.

Anna has always believed that she was Jon’s only target, since she never saw him mistreat their daughter or his mother. However, Anna grew suspicious a few weeks ago when she left Rebecca, who had developed a fever, home alone with Jon for the day. When Anna returned home, she noticed strange bruises on her daughter’s back. She confronted Jon about them, but he claimed that Rebecca had merely fallen. Another time, Anna came home to find Mirabel’s lip bleeding, though Jon said that Mirabel must have accidentally bit it while chewing.

These events were the last straw for Anna, and she has decided to leave Jon. However, there are many obstacles in her path. Anna’s most pressing concern is the physical safety of herself and her family: she is terrified that Jon will hurt or kill her (or another family member) if she tries to leave.[122] Thus, Anna has decided to prioritize the following goals:

Keep Jon away from herself and her child.

Remove Jon’s guns and prevent him from obtaining new guns.

Obtain full custody of her child.

Protect her mother-in-law from Jon.

Remain in the family home and kick Jon out.

Domestic violence law contains many remedies that may be able to help Anna achieve these goals. The following Sections will explore Anna’s available legal remedies.

A. Criminal Remedies

This Section will describe the remedies available to Anna under California criminal law. The California domestic violence statute, though, is limited in both who it protects and what it criminalizes.

The statutory definition of who counts as a victim of domestic violence is narrow. The California Penal Code defines domestic violence as “abuse committed against an adult or a minor who is a spouse, former spouse, cohabitant, former cohabitant, or person with whom the suspect has had a child or is having or has had a dating or engagement relationship.”[123] Notably, courts have interpreted “cohabitant” to mean “those living together in a substantial relationship—one manifested, minimally, by permanence and sexual or amorous intimacy.”[124] Thus, batterers are not liable for criminal domestic violence when they harm a child or other non-romantic partner with whom they reside.[125] In addition, people who are in non-traditional relationships may struggle to find recourse under this statute. Here, the criminal domestic violence statute includes Jon’s abuse of Anna, but does not include Jon’s abuse of Rebecca or Mirabel. Therefore, Jon’s abuse of Rebecca or Mirabel would have to be prosecuted under child abuse statutes, elder abuse statutes, or general assault and battery statutes.

The statutory definition of what counts as domestic violence is also narrow. The California Penal Code limits domestic violence to “intentionally or recklessly causing or attempting to cause bodily injury, or placing another person in reasonable apprehension of imminent serious bodily injury to himself or herself, or another.”[126] Defining abuse as “serious bodily injury” or even “bodily injury” excludes many other types of abuse that may not cause immediate damage, but can nevertheless exact significant psychological and physical damage. For example, Anna may not be seriously physically injured if Jon pushes her around the house; however, if Jon ritualistically pushes Anna around the house every time she arrives home from work, he inflicts a serious psychological toll.

The California Penal Code criminalizes domestic violence assault under sections 273.5 and 243(e)(1). A person is guilty of felony domestic violence assault if they “willfully inflict[] corporal injury resulting in a traumatic condition” on a recognized victim.[127] Section 243(a)(1) is a misdemeanor, but section 273.5 is a “wobbler,” meaning that prosecutors can charge the domestic violence as a felony or misdemeanor. Section 273.5 criminalizes willful conduct that inflicts a “traumatic condition” on a victim.[128] In this section, a traumatic condition means “a wound, or external or internal injury, including, but not limited to, injury as a result of strangulation or suffocation.”[129] Generally, police will treat an assault that results in a corporal injury as a felony and treat all other assaults as misdemeanors. Jon may also be liable for criminal marital rape, which is a felony in California.[130] Notably, the associated punishment for marital rape is far less severe than for nonmarital rape.[131]

As described in Part I, California has several special policies to handle domestic violence cases under criminal law. First, California is a pro-arrest state.[132] This means that officers are encouraged, but not required, to arrest domestic violence offenders if there is probable cause that an offense has been committed. However, arrest is mandatory if there is probable cause that the perpetrator has violated a restraining order.[133] Second, in California, “dual arrests” are discouraged, but not prohibited.[134] This requires officers to identify and arrest the “dominant aggressor” in the relationship, rather than arresting both of the people involved in the altercation.[135] However, in California, each DA’s office has a different policy regarding no-drop prosecutions.[136] For example, San Diego and San Francisco both have no-drop policies for domestic violence. Notwithstanding this policy, San Francisco prosecutors have also been criticized for under-prosecuting domestic violence cases.[137] Third, if the prosecutor does pursue the case, successful prosecution will be made easier by California’s special evidentiary rules for domestic violence cases, which allow into the record what would otherwise be inadmissible propensity evidence[138] and hearsay evidence.[139]

Therefore, if Anna wants to press criminal charges, her first stop is the police station. Ultimately, however, the prosecutor will decide whether to pursue felony or misdemeanor criminal charges against Jon. If a prosecutor does file charges against Jon, the prosecutor may also request, or the presiding court may decide to issue on its own, a criminal protective order.[140] This order would prevent Jon from contacting Anna and Rebecca and would also prohibit Jon from possessing guns.[141]

If the prosecution successfully convicts Jon of a felony or a misdemeanor, Jon will be subjected to strict probationary requirements. If not already in place, the court will issue a criminal protective order against him, which would also prevent Jon from possessing guns.[142] Furthermore, he will be required to complete California’s one-year batterer’s program.[143] A judge may also require Jon to reimburse Anna for expenses incurred as a direct result of his offense.[144]

However, there are limitations to a criminal prosecution. The definition of domestic violence is fairly restrictive and does not include many of the forms of abuse that Anna has suffered. While this criminal protective order can be issued to protect both Anna and her daughter, it will not be issued to protect Mirabel.[145] Furthermore, the prosecutor will have to prove their case against Jon beyond a reasonable doubt, which can be a particularly difficult burden to meet in a domestic violence case, as will be discussed further in the next Section.

Beyond the limited scope of the available criminal remedies, there are many other reasons why Anna might be reluctant to involve the police and criminal justice system.

First, Anna might fear that the police won’t believe her. Considering the police’s shoddy record with domestic violence, this fear is entirely rational. If they don’t believe her, she is in serious danger of Jon retaliating against her for involving the police.

Second, even if the police do believe her, the prosecutor might not bring charges. In other words, to pursue criminal charges, Anna has to put her fate in the hands of police officers and prosecutors who may not thoroughly pursue remedies on Anna’s behalf. If Anna lives in a no-drop prosecution state, she could be subpoenaed and forced to testify. She could even be jailed for refusing to testify.

Third, Anna might be afraid that calling the police will result in disastrous consequences, such as the police killing Jon. Anna might be particularly scared of this outcome if she or Jon are people of color. Anna might also be worried about the police harming her. Furthermore, if Anna fought back during the assault, there is a serious risk that the police will arrest her as well as Jon, because California permits dual arrests in domestic violence cases.[146] If Anna gets arrested, she risks losing custody of Rebecca, and any public benefits she may be receiving. She could also lose her job.

Fourth, even if she isn’t arrested, Anna still risks losing custody of Rebecca. In some states, survivors of domestic violence can lose custody of their children if the state decides that they have failed to protect their children from domestic violence.[147]

Fifth, Anna might be afraid of immigration consequences. If Jon isn’t a citizen, he risks deportation or losing his residency if he acquires a criminal conviction. If Anna’s immigration status is dependent on her marriage to Jon, she assumes similar risks.[148]

Sixth, Anna simply may not want Jon to suffer criminal penalties: if Jon were convicted of felony domestic violence, he would face up to four years in state prison and a fine of up to $6,000; if Jon was convicted of misdemeanor domestic violence, he would face up to a year in the county jail and a $2,000 fine.[149] While Anna may want to leave Jon forever, that does not necessarily mean she wants him to be in prison.

Seventh, if Anna is utilizing public housing, she risks losing this benefit if she is determined to be a “nuisance” for making too many police calls. In addition, if Jon is convicted and resumes living with Anna, she could lose her public housing for allowing a convict to live with her.

In sum, there are many rational reasons why Anna might decide that she does not want to involve the police or the criminal justice system at this time.

B. Family Law Remedies

This Section will describe the remedies available to Anna under California family law. The California Family Code defines domestic violence as abuse against a current or former spouse, cohabitant, dating partner, fiancée, parents of one’s child, or any other person related by “consanguinity or affinity within the second degree.”[150] This definition of domestic violence affirmatively protects Anna, her daughter, and her mother-in-law. It also provides a far more expansive definition of abuse, including: causing or attempting to cause bodily injury, sexual assault, and forcing someone to fear serious bodily injury to themselves or another.[151] Furthermore, this definition of abuse “is not limited to the actual infliction of physical injury or assault.”[152] This allows Anna to prove that she and her family are suffering from domestic violence by pointing to spoken, written, and other forms of emotional and psychological abuse.

Under California family law, Anna’s first remedy is to apply for a domestic violence restraining order (DVRO).[153] A judge can issue this order to protect Anna, Rebecca, and Mirabel.[154] The presiding judge can also order Jon to move out of their home.[155] Perhaps most importantly, the DVRO can prohibit Jon from owning guns and ammunition.[156] It can also require him to take the same one-year batterers program that is assigned for criminal convictions of domestic violence.[157]

Next, Anna will likely want to sue for full custody of Rebecca. The California Legislature has declared that “children have the right to be safe and free from abuse, and that the perpetration of child abuse or domestic violence in a household where a child resides is detrimental to the health, safety, and welfare of the child.”[158] Issues of custodial arrangements turn on what’s in the best interest of the child.[159] Judges must consider a parent’s abuse of the child or of the parent of that child in making that determination.[160] Because subjecting a child to domestic violence—even if the child is not directly harmed—constitutes a harm to the child in and of itself, California provides a statutory presumption against awarding custody to the parent who perpetrated domestic violence against the child, or against the other parent.[161] Therefore, if Anna can prove domestic violence, custody negotiations would begin with the assumption that Anna should have custody of Rebecca, and it would be Jon’s burden to prove otherwise.[162]

C. Civil Law Remedies

This Section will describe the remedies available to Anna under California civil law. Although the domestic violence restraining order would provide Anna the most protections in these circumstances, Anna could also pursue a civil harassment restraining order (CHO) under California Civil Procedure Code section 527.6. A judge can grant a civil harassment restraining order in response to behaviors that would cause a reasonable person to “suffer substantial emotional distress,” including “unlawful violence, a credible threat of violence, or a knowing and willful course of conduct directed at a specific person that seriously alarms, annoys, or harasses the person, and that serves no legitimate purpose.”[163] Through a CHO, a judge could order Jon to stay away from Anna and any other member of her household, and could even prohibit Jon from possessing guns if the judge found that Jon had used force or violence.[164]

Anna can also pursue civil money damages. California Civil Code section 1708.6 creates liability for the tort of domestic violence. This provision uses the California Penal Code definitions of what constitutes abuse, and who qualifies as a victim of domestic violence.[165] This means that survivors of domestic violence can sue their abusers for their injuries and receive general damages, special damages, punitive damages, equitable relief, injunctions, costs, attorney’s fees, and “any other relief that the court deems proper.”[166] In addition, California Civil Code section 52.4 creates a civil action for gender violence, which includes domestic violence, even in situations where the survivor cannot prove a physical injury.

Anna, like most domestic violence survivors, had no idea that she could sue Jon for money damages. When Anna found out about this remedy, it appealed to her because she has chronic health problems from the years of abuse and was recently diagnosed with PTSD. Anna also expects that her daughter might need therapy to deal with some of the trauma that she has experienced. In addition, Anna has missed a lot of work over the years due to Jon’s abuse, and she would welcome recouping those wages. Anna knows that Jon currently has no money, but suspects that might change when she stops supporting him. Anna decides to initiate a civil suit with the aim of collecting the judgment from Jon if and when he finds a job. Thus, Anna adds a sixth goal to her list: money damages for current and expected medical expenses, and lost wages.

D. Alternative Justice Remedies

This Section will describe the remedies available to Anna outside of the traditional legal system. Anna may also be interested in pursuing remedies outside of criminal, family, or civil law remedies. A handful of scholars have advocated for restorative justice and transformative justice interventions to domestic violence.[167] Restorative and transformative justice systems are designed to respond to survivors’ needs and to focus on remedying the harm caused by the conduct rather than punishing the crime.[168] Meghan Condon has argued that “restorative justice provides a better avenue to justice for minority victims of domestic violence than participation in the traditional legal system” because it is more adaptable to the needs of the specific survivor.[169] Restorative justice is about bringing together the survivor, perpetrator, and other people affected by the crime in order to learn about each other and collectively agree on a penalty.[170] Ultimately, the penalty is designed to repair the harm done to the survivor.[171] A key component to restorative justice is “reintegrative shaming,” whereby the community makes clear that the harmful conduct is unacceptable but that the perpetrator is still essentially “good” and capable of being reintegrated into the community.[172] One model of restorative justice in the United States is victim-offender mediation.[173] Although there are a small handful of domestic violence restorative justice projects in the United States,[174] they are extremely rare, controversial, and under-researched. The success of such programs remains unclear.[175]

Given the rarity of formal restorative justice programs for domestic violence, this is probably not a realistic option for Anna at this time. However, Anna is still very much interested in informal community support and accountability as she attempts to leave Jon. For example, Anna would like the support of her church. If the church believes her, they may prevent Jon from attending church while she is there. The church would also be more likely to support Anna divorcing Jon, rather than advocating for marriage counseling. The church might also provide housing and food support as she navigates leaving Jon. In addition, the couple has some shared friends that Anna would like to keep in her life. Since Jon is such a good liar, Anna is worried that she will lose everyone if she leaves him because no one will believe her. The support of friends and family can make a critical difference in a survivor’s ability to permanently leave their abuser. Whether Anna’s fears about not being believed are well-founded or not, she is very concerned with proving to the people she loves that Jon has been abusing her.

In sum, even though a formal extralegal remedy may be unrealistic for Anna, there are many informal remedies that may vastly improve Anna’s quality of life.

E. Summary of Remedies

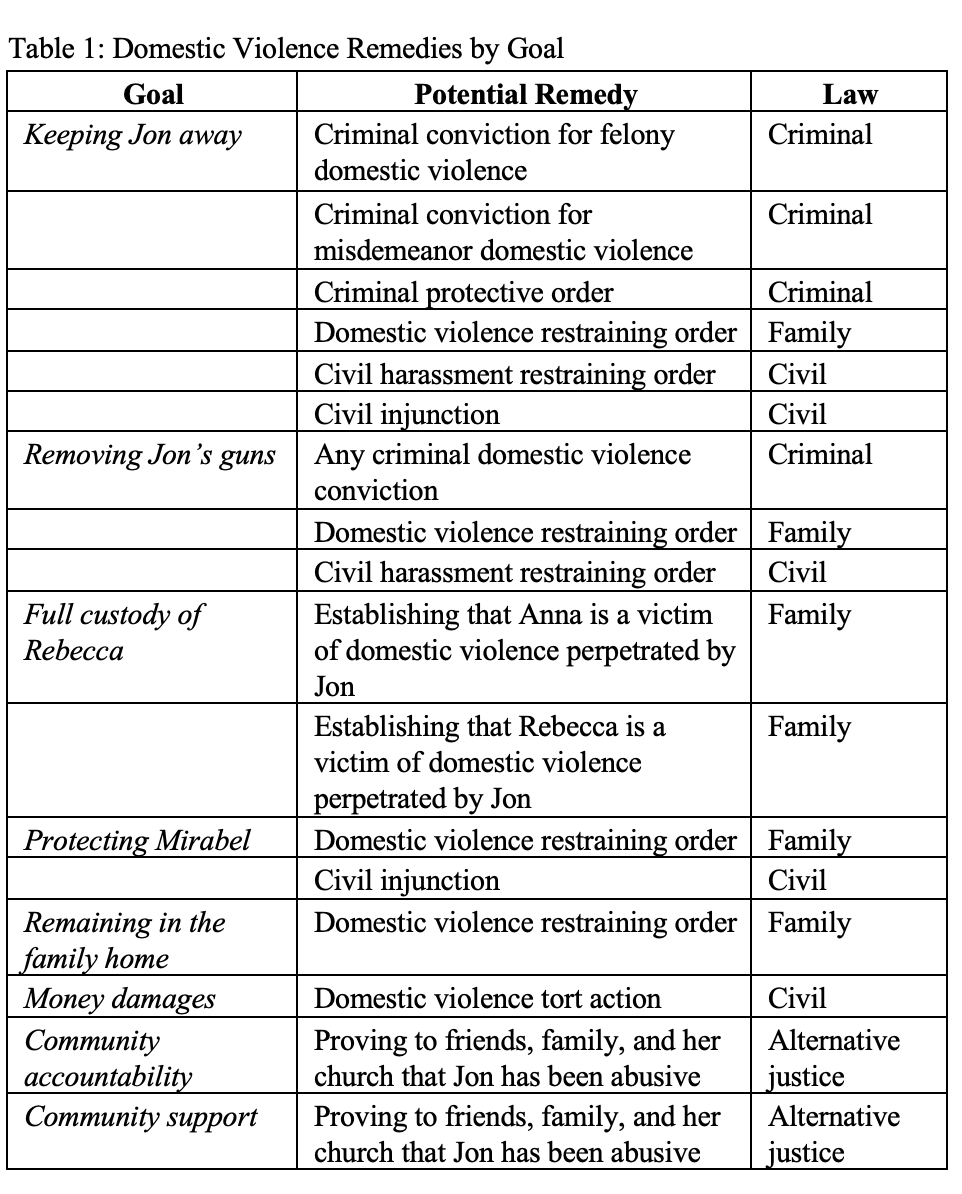

In summary, the following table outlines Anna’s goals and some[176] of the legal remedies available to accomplish each goal.

III. Proving Domestic Violence

This Section discusses: the processes of proving domestic violence in criminal, family, and civil legal proceedings; the difficulty of proving domestic violence; and the ways in which secret recordings can offer determinative evidence.

A. The Survivor’s Burden

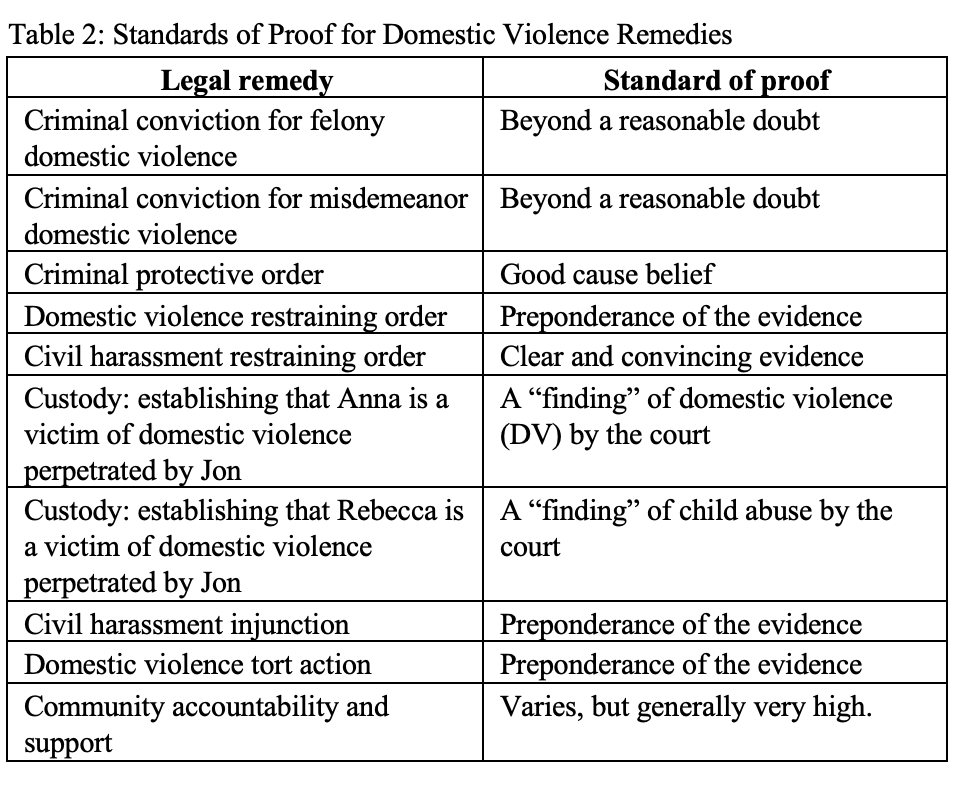

This Section will explain what Anna will have to prove to access the available remedies. Each proceeding requires a different standard of proof for establishing domestic violence. Furthermore, each proceeding follows different evidentiary rules to prove domestic violence.

A criminal prosecution has the highest burden of proof and the strictest requirements. The prosecutor must prove that domestic violence occurred beyond a reasonable doubt. A criminal protective order requires that a judge find “good cause belief” that the defendant poses some sort of threat to the survivor; this finding is essentially left to the discretion of the judge.[177]

Restraining orders have lower burdens of proof than criminal prosecutions. To secure a DVRO, Anna must prove the occurrence of “past abuse by a preponderance of the evidence.”[178] Judges exercise great discretion when determining whether abuse has occurred for the purposes of securing a DVRO. The relevant statute provides that a domestic violence restraining order may be granted upon a showing “to the satisfaction of the court, reasonable proof of a past act or acts of abuse.”[179] While this can work in Anna’s favor, results can vary depending on the judge’s views and background. Success is by no means guaranteed, and requests for DVROs are frequently denied by the courts.[180] To secure a CHO, Anna must prove that Jon has engaged in a course of conduct that qualifies as harassment by clear and convincing evidence.[181] This evidentiary standard is higher than that of a DVRO.

The burden of proof required in custody proceedings is fairly ambiguous. In order to secure the presumption that awarding Jon custody of Rebecca would be detrimental to Rebecca, Anna must prove that Jon has perpetrated domestic violence against either Anna or Rebecca within the past five years.[182] The court applies this presumption “upon a finding” that the party has committed domestic violence.[183] The finding requirement may be satisfied by evidence of a criminal conviction within the past five years for domestic violence or abuse.[184] However, it can also be satisfied by establishing the perpetrator’s “conduct” within the past five years.[185] Anna does not need to be successful in getting a DVRO or any of the other aforementioned remedies in order to secure this presumption.[186] In making this finding, courts shall consider “any relevant, admissible evidence submitted by the parties.”[187] In general, custody arrangements are extremely discretionary.[188]

Other civil remedies require lower burdens of proof. To secure civil damages, Anna must prove by a preponderance of the evidence that Jon caused domestic violence that resulted in injuries to Anna, Rebecca, or Mirabel. This means that Anna must prove that it’s “more likely than not” that Jon abused her or her family members. The following table summarizes the standards of proof for each legal remedy at issue.

Extralegal remedies do not have formalized burdens of proof. Of course, there is no formal standard for proving domestic violence to members of the community. The #MeToo movement has campaigned heavily for believing women[189] when they say there are survivors of gender crimes. The campaign’s existence, however, shows just how reluctant society has been to believe women.[190]

B. Why Is Domestic Violence So Difficult to Prove?

This Section will explore some of the reasons that domestic violence is harder to prove than other crimes.

Anna is very worried about proving what has been going on inside her home. The police have never been called to their home, so there are no police reports. Jon usually prevented her from seeing a doctor after his attacks, and so there is minimal medical documentation of his abuse. The one time she did visit a doctor after an episode, Anna told the doctor that she had slipped on ice and the doctor appeared to believe her. As discussed previously, Anna has not told anyone in her community about the abuse.

Anna’s situation is not at all uncommon. Domestic violence is very difficult to prove, in part because it usually occurs behind closed doors in private homes.[191] Survivors and victims frequently hide evidence of abuse from family, friends, medical practitioners, and law enforcement, often because they—typically correctly—fear the consequences of revealing the abuse more than they fear the abuse itself.[192] Abusers often play an active role in destroying and hiding evidence of their abuse. Given these factors, if and when a domestic violence case finally gets to court—be it for a criminal prosecution, restraining order, or custody battle—concrete evidence of abuse is often scant.[193]

Domestic violence is also difficult to prove because of evidentiary rules. Hearsay rules can prevent the admission of many types of evidence of particular relevance to domestic violence cases. The prosecutor or plaintiff can interview witnesses to the abuse, but the testimony of witnesses who only heard about the abuse from the survivor or victim will often be excluded on hearsay grounds. For example, if Anna had told a friend over the phone that Jon had hit her, but the friend never witnessed any violence or saw any marks on Anna, the friend would likely be prevented from testifying about Anna’s remarks to her. Admittedly, medical records are admissible, but their helpfulness can be limited if the survivor or victim had only visited infrequently, was adept at lying to medical professionals, or the file lacks thorough notes or pictures. In sum, the nature of domestic violence makes it very difficult to prove.

If Anna can’t prove that Jon has committed domestic violence, she will not be able to access any of the legal remedies described above. This means that Jon will keep his guns, stay in their home, and maintain contact with Anna, Rebecca, and Mirabel. If Anna decides to leave anyway, Jon will still be able to pursue partial or even full custody of Rebecca.[194] Anna won’t be able to secure the monetary damages she needs for medical care, counseling, and missed work. If Anna goes through with the divorce anyway, she could even end up paying Jon spousal support.[195]

Like many survivors of domestic violence, Anna has some idea of how hard domestic violence is to prove in court. This awareness is compounded by the fact that many abusers tell their targets that no one will believe them. The resulting doubt makes it even harder for survivors of domestic violence to leave or seek help, because they fear the consequences that their abusers will inflict on them if their attempts are unsuccessful. Survivors and victims often fear that their abusers will take partial or total custody of their children. Anna might rationally decide that it is better for their child if she remains in the house full-time as a buffer, rather than send Rebecca to her father’s house each weekend unsupervised.

There can also be serious consequences to initiating and losing a domestic violence legal proceeding. Pursuing any legal action against Jon is likely to infuriate him, potentially causing him to lash out against her and the rest of the family. An abuser is statistically more likely to kill their victim after the victim leaves the abuser.[196] If Anna leaves without the protections of a criminal protective order or domestic violence restraining order, she increases her risk of incurring catastrophic injuries or death. Even with one of these orders, Anna is still in great danger if she leaves. Consequently, Anna is reluctant to antagonize Jon unless she has a decent chance of prevailing in court.

C. Secret Recordings

In general, recordings provide powerful and persuasive evidence.[197] Perhaps the most powerful evidence of domestic violence is a video or audio recording of the abuse.[198] When cases come down to “he-said, she-said,” a recording can prove a damning tiebreaker.[199] Although the case law is very scant, secret recordings—when admitted as evidence—have been critical to a judge’s finding of domestic violence.[200]

Flores v. Reza, an unpublished California decision, is an example of how a secret recording can determine whether a person experiencing domestic violence is able to obtain relief. In Flores, a trial court granted Flores a restraining order against her husband, Reza, after listening to a recording secretly made by Flores.[201] After a recent beating, Flores bought a recorder, hid the device in her bra, and taped a communication with her husband.[202] After Flores testified at the hearing about Reza’s abuse, she was asked whether she had any support for her claims.[203] Flores explained that she had secretly made a recording that “would prove Reza had threatened to deport her and contained statements showing he knew she would not report the physical abuse because of her fears of deportation.”[204] Reza testified that he had never abused Flores, and Reza’s father testified to the same effect.[205] Without the recording, this case might well have been dismissed as “he-said, she-said.” But after listening to the recording, the trial court judge found that domestic violence had occurred by a preponderance of the evidence. The trial court issued a restraining order and granted the mother full custody.[206] Thus, this case shows the importance of secret recordings for proving that domestic violence occurred and obtaining two critically important domestic violence remedies—restraining orders and custody of one’s children.

However, Flores also shows how difficult it is to get such recordings admitted into court. The recording in Flores v. Reza was admitted as evidence at trial only because Reza’s lawyer didn’t know the law well enough to object.[207] On appeal, Reza argued that the admission of the recording was reversible error because evidence collected by eavesdropping was inadmissible under CEPA sections 631 and 632, and under Family Code section 2022.[208] However, his lawyer had failed to raise these objections at trial.[209] Thus, the appeals court responded, “Nice try, but we are not persuaded,” and found that the issue had been forfeited.[210] In other words, this case could have turned out in favor of Flores’s husband if he had raised his CEPA objections at trial. Furthermore, even though this recording was admitted as evidence, Flores still violated CEPA and could have been sued by Reza for civil damages, or even been prosecuted for felony or misdemeanor eavesdropping, as will be discussed in more detail in the following Section. Thus, this case also shows that batterers can weaponize California’s eavesdropping statute to prevent their victims from using the only concrete evidence of domestic violence they have, and thus prevent their victims from obtaining a remedy.

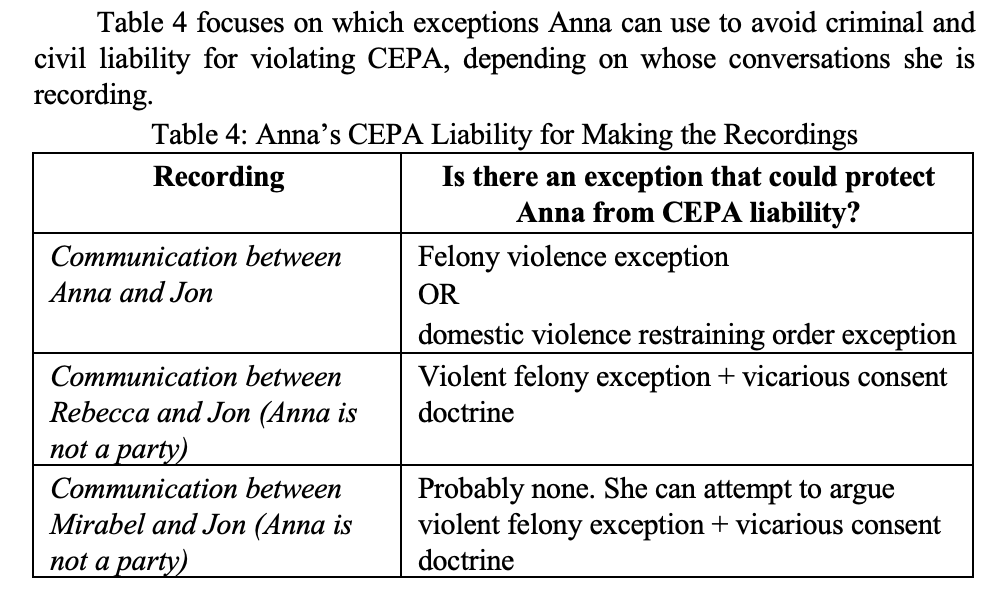

Shifting back to our hypothetical, suppose Anna consults some domestic violence forums and support websites to learn what kind of evidence she needs. They advise her to document as much of the abuse as she can, in the form of telling outside witnesses, taking photos of injuries, and, if possible, making recordings of the abuse. Anna decides to start pressing “record” on her iPhone during moments of tension where she expects violence is imminent. Anna wants to make three types of recordings. First, she wants to record communications between herself and Jon. Second, she wants to place a hidden recording device to capture communications between Jon and Rebecca. Third, she wants to place a hidden recording device to capture communications between Jon and Mirabel. She hopes to show these recordings in court and to her community in order to prove that Jon is abusing all three of them.

IV. Anti-Eavesdropping Statutes and Domestic Violence Litigation

This Section discusses how anti-eavesdropping statutes affect people experiencing domestic violence. Part IV.A summarizes the functions and consequences of federal and California anti-eavesdropping statutes. Part IV.B details various methods and arguments that practitioners can use to get around these statutes. Part IV.C applies the previous two Sections to our hypothetical to illustrate how these statutes affect Anna’s ability to access domestic violence remedies.

The federal anti-eavesdropping prohibition is found in Title III of the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Street Acts of 1968.[211] This statute prohibits private citizens from intercepting or recording private communications.[212] However, case law has interpreted this statute as a “one-party consent” rule that still permits private citizens to record any of their own conversations or interactions with other people.[213] This means that it is perfectly legal for private citizens to secretly record their own conversations or interactions with another, regardless of that other person’s knowledge or consent.[214]

The majority of states have followed the federal example in enacting one-party consent statutes.[215] California is one of a handful of states that have enacted a far stricter version in the form of The California Electronic Privacy Act (CEPA).[216] CEPA prohibits private citizens from recording confidential communications unless everyone involved in the conversation has consented to being recorded.[217]

Violators of CEPA are subject to both criminal and civil liability. Penal Code section 631(a) provides that violators can be convicted for misdemeanor or felony wiretapping, which is “punished by a fine not exceeding two thousand five hundred dollars ($2,500), or by imprisonment in a county jail not exceeding one year.”[218] Furthermore, Penal Code section 637.2 creates a civil action for victims of wiretapping, allowing them to sue for money damages.[219]

Recordings made in violation of CEPA are inadmissible unless an exception applies, as discussed in the following Section. Penal Code section 632(d) provides that any evidence “obtained as a result of eavesdropping upon or recording a confidential communication” is inadmissible as evidence in any judicial, administrative, legislative, or other proceeding, except to prove that a CEPA violation has occurred.[220] This constitutes a blanket prohibition on admitting any recording for any judicial proceeding that was created in violation of CEPA.[221]

Just in case CEPA was not sufficient, the California Family Code created a special provision to reinforce the inadmissibility of surreptitious recordings. Family Code section 2022 provides that “evidence collected by eavesdropping” in violation of CEPA is inadmissible.[222] Furthermore, if it appears that such a violation exists, “the court may refer the matter to the proper authority for investigation and prosecution.”[223] The potential for criminal and civil liability for violating eavesdropping statutes is not an idle threat.[224]

For our purposes, this means that survivors of domestic violence who wish to create secret recordings of their abuse risk criminal and civil liability: they could be prosecuted for felony or misdemeanor eavesdropping, and their abusers could sue them for money damages. Furthermore, their recordings will be inadmissible as evidence against their abusers unless an exception applies—as will be explained in the next Section.

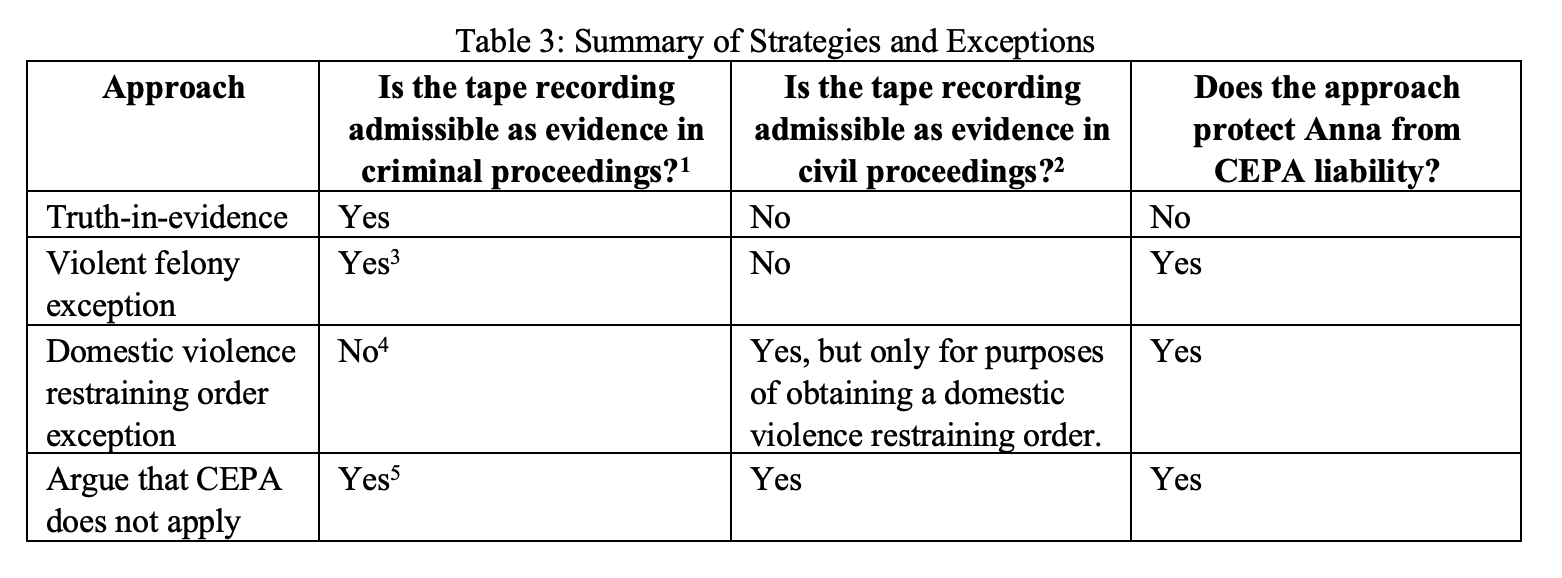

A. Circumventing CEPA

This Section explores methods of circumventing CEPA in order to avoid civil and criminal liability or render a secret recording admissible. Because CEPA is its own exclusionary rule, evidentiary exceptions typically used by domestic violence practitioners are useless. Anna must find a way to get around CEPA just to get her recordings before the court. Unfortunately, there is no published case law interpreting CEPA in the domestic violence context.[225] Instead, I have pulled from statutory language, unpublished decisions, and analogous case law to identify four different strategies to get Anna’s secret recording into court.[226] This Section will explain how to argue each strategy, as well as their pros and cons.

1. The Right-to-Truth-in-Evidence Provision

In 1982, California voters enacted Proposition 8, which included the “Right-to-Truth-in-Evidence” provision.[227] This provision instructs that “[e]xcept as provided by statute hereafter enacted by a two-thirds vote of the membership in each house of the Legislature, relevant evidence shall not be excluded in any criminal proceeding.”[228] In People v. Guzman, the California Supreme Court found that CEPA’s exclusionary rule[229] had been abrogated by the truth-in-evidence provision.[230] At trial, the jury had convicted Guzman of two counts of committing a lewd and lascivious act upon a child.[231] As part of the evidence, the jury heard a recorded phone conversation between the mother of one of the victims and the defendant’s niece.[232] The mother had secretly recorded that conversation without the niece’s consent in violation of CEPA, but the trial court admitted the recording pursuant to the truth-in-evidence rule.[233] The California Supreme Court affirmed this decision, holding that recordings made in violation of section 632.1 are admissible in criminal proceedings as long as the evidence is relevant and is not otherwise barred by the U.S. Constitution.[234]

For purposes of our hypothetical, this means that Anna’s recordings are admissible against Jon for purposes of criminal proceedings. However, the truth-in-evidence rule has absolutely no effect on civil proceedings: “it is undisputed that civil, administrative, legislative, and other noncriminal proceedings are unaffected by Proposition 8.”[235] Guzman attempted to argue that such an outcome violates equal protection because criminal defendants would be treated differently than civil defendants in that the secret recordings would be admissible against the former, but not the latter.[236] The California Supreme Court rejected this argument, reasoning that it is constitutionally permissible for the electorate to treat criminal and civil defendants differently.[237] Thus, Proposition 8 and Guzman will only allow Anna’s recordings to be admitted as evidence in a criminal prosecution against Jon.

Furthermore, Proposition 8 and Guzman do not change Anna’s liability for making the recording in the first place. The Guzman court noted that even though recordings taken in violation of CEPA are admissible as evidence in criminal proceedings, it is still illegal to make such recordings in the first place.[238] Thus, even if Anna’s tape was admitted in a criminal prosecution, she could still be criminally prosecuted or sued by Jon for taking the recording.

In sum, this strategy will allow Anna’s recordings to be admissible in criminal court, but will not protect her from civil or criminal liability.

2. The Violent Felony Exception