All Disputes Must Be Brought Here: the Future of Multidistrict Litigation

Multidistrict litigation (“MDL”) is an immensely powerful tool. In an MDL, cases that share a common question of fact are consolidated in a single district for pretrial proceedings. MDLs abide by the general principle that governs all transfers within the federal system: because transfer is no more than a “housekeeping measure,” an action retains the choice-of-law rules of the state in which it was filed. If a case filed in California is transferred to an MDL pending in Iowa, the transferee court in Iowa applies California’s choice-of-law rules. As a result, the cases maintain their identities through the retention of their individual home state’s choice-of-law rules. It is thus a critical feature of MDLs—which have far fewer procedural protections than class actions—that transfer to an MDL does not change the applicable law for any individual action. In non-aggregate litigation, this general transfer rule no longer applies, however, when a case is transferred pursuant to a forum-selection clause. Under the Supreme Court’s 2013 decision in Atlantic Marine Construction Co. v. U.S. District Court, the transferee court applies its own choice-of-law rules instead. Thus, if a case filed in California is transferred to Iowa in accordance with a forum-selection clause, the transferee court in Iowa applies Iowa’s choice-of-law rules. Although Atlantic Marine involved a non-aggregate proceeding, courts have begun to consider whether this principle should control choice of law in complex litigation governed by a forum-selection clause. This Note argues that it should not. To begin, extending Atlantic Marine to the MDL context might allow the fact of consolidation to change the outcome in a case. Doing so would also expand due process concerns already inherent in aggregate proceedings, and MDL is not an appropriate forum in which to allow parties discretion to craft their own rules of dispute resolution. Accordingly, to preserve the integrity of the MDL process, MDL courts should consistently apply the choice-of-law rules of the transferor court, even when an action is governed by a valid forum-selection clause.

Table of Contents Show

Introduction

The United States judicial system largely operates under a regime of vertical uniformity. When a case can be litigated in either state or federal court, Erie Railroad v. Tompkins requires that a federal court sitting in diversity apply state substantive law.[3] And when there is a dispute as to choice of law, Klaxon Co. v. Stentor Electric Manufacturing Co. requires that a federal court apply the choice-of-law rules of the state in which it sits.[4] The principle of vertical uniformity also justifies protecting the plaintiff’s initial choice of forum when a case changes venue within the federal system: an action transferred pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1404(a) carries with it the choice-of-law rules of the state in which it was originally filed.[5] This ensures that the outcome of a case will not hinge on the “accident” of diversity jurisdiction, thus maintaining uniformity between the state and federal courts in litigation governed by state law.[6]

Vertical uniformity is particularly important in complex litigation because a case governed by state substantive law might find itself not only in federal court, but also in some type of consolidated federal action. Multidistrict litigation, or “MDL,” provides an apt example. Of the procedures that have developed to administer complex litigation, MDL looms large. Under the MDL statute, 28 U.S.C. § 1407, a set of civil actions that involves “one or more common questions of fact” may be consolidated in a selected district for pretrial proceedings.[7] As the availability of nationwide class actions has shrunk, aggregate litigation has shifted dramatically toward MDLs: approximately one-third of all federal civil cases currently belong to a pending MDL.[8] As Congress considers further changing the class action device, MDLs will only continue to grow in importance.[9]

To preserve consistency between ordinary and complex proceedings, an action transferred to an MDL retains the choice-of-law rules of the transferor court.[10] If a plaintiff who files an action in Washington finds the case transferred thousands of miles to an MDL in Pennsylvania, Washington’s choice-of-law rules will at least be transferred with it. If the defendant in the MDL then files, for example, a motion to dismiss, the motion will be adjudicated for that plaintiff under Washington’s choice-of-law rules—just as it would be in federal court in Washington, and just as it would be in state court in Washington. In this context, vertical uniformity helps ensure that consolidation does not change the outcome of a case.

This prioritization of vertical uniformity is not, however, absolute. Under the Supreme Court’s recent decision in Atlantic Marine Construction Co. v. U.S. District Court, an action transferred to enforce a valid forum-selection clause is instead governed by the choice-of-law rules of the transferee court.[11] The Court explained that “a plaintiff who files suit in violation of a forum-selection clause” is not entitled to any “‘privilege’ with respect to its choice of forum,” and therefore has no claim to any “concomitant ‘state-law advantages.’”[12] A valid forum-selection clause thus controls both the location for litigation and the applicable choice-of-law rules.[13]

At first glance, Atlantic Marine might seem irrelevant to MDL. The Judicial Panel on Multidistrict Litigation, which manages the administration of MDL proceedings, has consistently held that it is not bound by a forum-selection clause when selecting the location for an MDL, and Atlantic Marine itself involved an ordinary, rather than a complex, proceeding.[14] An argument can be made, however, to extend Atlantic Marine to choice of law in MDL proceedings, particularly given the similarities between the MDL statute, Section 1407, and the federal transfer statute, Section 1404. An MDL court might partially enforce a forum-selection clause by applying the choice-of-law rules of the contractually selected forum during pretrial proceedings—and would likely be tempted to do so to simplify an otherwise onerous choice-of-law analysis.

But this simplification comes at a cost. First, Atlantic Marine is premised on a valid forum-selection clause, and an MDL court is likely to apply its own law to assess validity.[15] When the MDL court and the transferor court differ in their assessment of validity, the involvement of the MDL court has the potential to change the outcome of a case. This result is highly problematic. Consolidation should not impact parties’ substantive rights, and selecting a particular MDL court should not lead to a different decision in a case.[16] Moreover, MDL is designed to exist as a collection of individual actions, not as one mass action. Applying a forum-selection clause to standardize choice of law across all of the pending actions in an MDL would undermine this structure and make it easier to elide differences among individual actions. Erasing these choice-of-law distinctions would also jeopardize plaintiffs’ due process rights when the parties inevitably consider settlement. By contrast, allowing actions to retain the choice-of-law rules of their transferor states helps preserve their individuality and counteract the pressures of aggregation.[17]

As a result, even where a forum-selection clause would dictate choice of law in a non-aggregate proceeding, this Note argues that it should not dictate choice of law in an MDL. This is a shift from the general guiding principle that “whatever choice-of-law rules we use to define substantive rights should be the same for ordinary and complex cases.”[18] In a typical situation, treating a complex case the same as an ordinary case helps ensure that consolidation does not result in a change in outcome. In this context, however, the opposite is true. To preserve the individual rights of litigants, the MDL court should choose not to enforce a forum-selection clause during pretrial proceedings—even when the transferor court would enforce the clause in an ordinary proceeding. Instead, all pending MDL cases should be controlled by the choice-of-law rules of their respective home states during pretrial proceedings.

Part I of this Article lays out the choice-of-law framework for diversity actions in the federal courts and discusses the shift created by the Supreme Court’s decision in Atlantic Marine. Part II introduces multidistrict litigation, with a focus on the selection of the transferee district and the operation of choice of law within an MDL proceeding. This Section also explains how forum-selection clauses interact with MDL, and considers whether Atlantic Marine might be interpreted to impact MDL practice. Finally, Part III argues that the choice-of-law holding in Atlantic Marine should be cabined to ordinary litigation. In particular, this Section explains how enforcing a forum-selection clause as to choice of law in an MDL might create MDL-specific outcomes and endanger plaintiffs’ due process rights.

I. Prioritization of Vertical Uniformity

Following Erie Railroad v. Tompkins, a series of Supreme Court decisions gave precedence to maintaining the “critical identity” between the federal and state courts in litigation governed by state substantive law.[19] The Court had, until recently, hewed strictly to the principle that adjudication in federal court should not impact the outcome of a case that would otherwise be decided in state court. Under this line of cases, an action filed in state court, removed to federal court, and transferred to a different federal district should be decided the same way as a non-diverse state action. The Court took a step away from this commitment, however, in Atlantic Marine Construction Co. v. U.S. District Court.[20] Emphasizing the importance of “holding parties to their bargain,” the Court prioritized enforcing a forum-selection clause over maintaining uniformity between the state and federal courts.[21] This Section explores the Court’s historic concern with vertical uniformity in the context of ordinary litigation and explains why Atlantic Marine should be understood as a significant departure from that post-Erie tradition.

A. The Accident of Diversity Jurisdiction

When Pennsylvania citizen Harry Tompkins was injured by a train in 1934, he could sue the New York-based Erie Railroad Company in either state or federal court.[22] Suing in state court was not an attractive option. Pennsylvania law allowed recovery only for recklessness, which Tompkins could not prove.[23] Although New York law was more generous, under New York’s choice-of-law rules the court would apply the law of the place of injury, and Tompkins would again be subject to Pennsylvania law.[24] Instead, Tompkins wanted to take advantage of federal general common law, which allowed recovery for negligence.[25] Tompkins filed suit in federal court in New York, expecting to benefit from the rule of Swift v. Tyson that allowed federal courts to apply general common law in diversity actions.[26]

Surprising everyone, except perhaps future generations of civil procedure students, the Court overruled Swift and held that a federal court sitting in diversity must apply state substantive law.[27] As Justice Brandeis famously asserted, “[t]here is no federal general common law.”[28] Despite his best efforts, Tompkins was still subject to Pennsylvania law.[29] The Court’s decision was driven in part by its concern with the “grave discrimination by non-citizens against citizens” tolerated under the Swift regime.[30] Because Swift allowed for different outcomes depending on whether an action was heard in state or federal court, “the doctrine rendered impossible equal protection of the law.”[31]

Erie did not, however, wipe out disuniformity. Instead, the decision prioritized vertical uniformity—ensuring that a state court and a federal court in the same state would reach the same decision—while allowing for horizontal disuniformity among the federal courts of different states.[32] Under this approach, the resolution of a case would not be impacted by the “accident” of diversity jurisdiction, even if it allowed for different outcomes among the federal courts.[33] Of course, obtaining different outcomes in litigation under state law is inherent in a judicial system that encompasses fifty distinct state-court systems.[34] Indeed, Tompkins almost certainly would have fared better had his accident occurred in a different state, the majority of which required only negligence for recovery.[35]

The facts of Erie did not force the Court to grapple with choice-of-law issues; given the location of the accident, there was no question that Pennsylvania law would apply.[36] But choice of law is critical. It frequently has a dispositive impact on the outcome of a case, and how the federal courts approach choice of law in diversity actions largely controls the degree of horizontal disuniformity tolerated under Erie. Prior to Erie, federal courts followed their own choice-of-law rules in diversity actions.[37] If this approach prevailed, a case might still be decided differently in federal court, despite the mandate of Erie. By comparison, requiring federal courts to follow state choice-of-law rules would further the goal that diversity jurisdiction not alter the outcome of a case.[38] The courts of appeals quickly split on the issue, and, three years after Erie, the Supreme Court considered the question.

In Klaxon Co. v. Stentor Electric Manufacturing Co., a choice-of-law conflict arose after a Delaware corporation sued its New York purchaser in federal district court in Delaware for failing to use best efforts to sell its products, thereby diminishing what the corporation expected to recover under its contract.[39] After the corporation won at trial, an issue arose over whether it was entitled to prejudgment interest.[40] The court applied New York law under federal choice-of-law principles and awarded the interest.[41]

The Supreme Court reversed, holding that a federal court sitting in diversity must apply the choice-of-law rules of the state in which it sits.[42] Reaffirming its prioritization of vertical uniformity, the Court held that Delaware had the authority to decide which law governed an action decided under state law.[43] “Any other ruling would do violence to the principle of uniformity within a state upon which the Tompkins decision is based.”[44] The decision further confirmed that a state’s choice-of-law rules are part of its substantive law and a matter of state policy.[45] The Court thus remanded the case to the district court to apply Delaware’s choice-of-law rules.[46]

Recognizing that its holding allowed for horizontal disuniformity among the federal courts, the Court explained that such disuniformity “is attributable to our federal system, which leaves to a state . . . the right to pursue local policies diverging from those of its neighbors.”[47] If New York and Delaware take different positions on the availability of prejudgment interest, and even on which state’s law should govern the availability of interest in a particular case, then so be it.[48] The Court was willing to accept that the outcome of a case might hinge on which state it was filed in, as long as the federal court would reach the same outcome as its local state court.

B. Transfer as a “Housekeeping” Measure

Klaxon provides plaintiffs with a powerful lever to pull at the outset of an action. Because choice of forum is accompanied by choice of law, plaintiffs benefit greatly from the opportunity to select in which state they file. Whether this power extends to transferred actions determines whether a plaintiff’s choice of forum will also control the applicable law for a case ultimately adjudicated in a different district.

Before the enactment of 28 U.S.C. § 1404(a), which governs change of venue for federal civil actions, a federal court would dismiss for forum non conveniens if it decided that an action properly belonged in a different district.[49] The plaintiff could then refile, and the new district court would apply the choice-of-law rules of the state in which it sat under Klaxon. After passage of Section 1404(a) created the possibility of transfer, the transferee court was faced with the decision whether to apply the choice-of-law rules of its own state or the state in which the case was originally filed.

The Supreme Court considered this issue in Van Dusen v. Barrack.[50] The case involved a Philadelphia-bound plane that crashed in Boston Harbor shortly after takeoff.[51] Over 150 plaintiffs sued the airline for personal injury and wrongful death in federal court in both Massachusetts and Pennsylvania. When the Pennsylvania actions were transferred to the District of Massachusetts pursuant to Section 1404(a), the Pennsylvania plaintiffs faced the possibility of severely limited recovery.[52] If the court followed the choice-of-law rules of the state in which it sat, the Pennsylvania plaintiffs would be subject to a strict damages cap under Massachusetts law.[53] If the court followed the choice-of-law rules of the transferor court, then Pennsylvania law—which did not include a cap—would apply instead.[54]

Describing transfer under Section 1404(a) as a “housekeeping measure,” the Court held that a transferee court must apply the law of the state in which an action was originally filed.[55] Because “the critical identity to be maintained is between the federal district court which decides the case and the courts of the State in which the action was filed,” the law that would have governed absent the change in venue remains in force.[56] Plaintiffs thus retain the choice-of-law benefits of the forum they initially select, even if they cannot retain the forum itself. As the Court noted, “[t]here is nothing . . . in the language or policy of Section 1404(a) to justify its use by defendants to defeat the advantages accruing to plaintiffs who have chosen a forum which, although it was inconvenient, was a proper venue.”[57]

Once again, the Court was willing to tolerate horizontal disuniformity to maintain vertical uniformity, despite its leading to different recoveries in a consolidated action involving the same accident. This commitment to vertical uniformity continued in Ferens v. John Deere Co., in which the Court reiterated that transfer does not change the applicable choice-of-law rules—even where a plaintiff initiates the transfer.[58] While recognizing that its holding allowed for gamesmanship by plaintiffs, the Court again explained that diversity jurisdiction should not allow for a change in the applicable state law.[59] The Court did not address, however, whether this principle applies when the parties select a forum prior to the litigation.

C. The Shift in Atlantic Marine

Under Van Dusen and Ferens, a plaintiff’s choice of forum dictates the applicable choice-of-law rules, even when a case is transferred, and even when that transfer is initiated by the plaintiff. In Atlantic Marine, the Supreme Court addressed whether this principle would hold where the plaintiff selects a forum in contravention of the parties’ contractual forum-selection clause.[60] The case involved a contractual dispute between a Texas corporation, J-Crew Management, Inc., and a Virginia corporation, Atlantic Marine Construction Co.[61] The parties’ contract included a forum-selection clause that stated “all . . . disputes . . . shall be litigated in the Circuit Court for the City of Norfolk, Virginia, or the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia, Norfolk Division.”[62] J-Crew brought suit over a payment dispute in the Western District of Texas, and Atlantic Marine moved to enforce the clause via three potential mechanisms: a motion to transfer under 28 U.S.C. § 1404(a); a motion to transfer under 28 U.S.C. § 1406(a), which governs actions filed in “the wrong division or district”; and a motion to dismiss for “improper venue” under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(3).[63]

The Court first explained that Section 1404(a) was the correct procedural mechanism for enforcing the forum-selection clause.[64] Because venue was “otherwise proper” in the Western District of Texas, neither Section 1406 nor Rule 12(b)(3) applied.[65] The Court then held that a district court should generally abide by the terms of a forum-selection clause, provided that the clause is contractually valid.[66] Specifically, the presence of a forum-selection clause alters the traditional transfer calculus in two ways: (1) the plaintiff’s choice of forum “merits no weight,” and (2) the parties’ private interests must be deemed to “weigh entirely in favor of the preselected forum.”[67] As a result, absent unusually persuasive public-interest factors, a district court should transfer a case to its contractually selected venue.[68]

In a break with Van Dusen, the Court further held that the transferee court had to apply the choice-of-law rules of its own state, rather than those of the transferor state.[69] By “flout[ing] its contractual obligation,” the plaintiff had abdicated its right to a traditional housekeeping transfer that would carry with it the original forum’s choice-of-law rules.[70] Accordingly, Virginia’s choice-of-law rules governed instead.[71] The Court thus prioritized “holding parties to their bargain,” even when doing so would disrupt the vertical uniformity prized by Klaxon and Van Dusen.[72]

Under Atlantic Marine, a forum-selection clause operates to select the forum as well as the applicable choice-of-law rules—but only when the clause is valid.[73] By conditioning its decision on the validity of the clause, the Court’s decision partially overruled its earlier holding in Stewart Organization v. Ricoh Corp.[74] In Stewart, the plaintiff filed a diversity action in federal court in Alabama, contrary to the parties’ contractually selected venue of New York.[75] When the defendant moved to transfer pursuant to the contract, the plaintiff argued that the clause was void under Alabama law.[76]

The Court first held that Section 1404(a) controlled the parties’ forum dispute.[77] Because transfer does not change the law applicable to a case, the Court explained that Section 1404(a) was “doubtless capable of classification as a procedural rule.”[78] As such, the federal statute governed whether the dispute belonged in New York rather than Alabama.[79] Notably, though, the Court never determined—under either federal or state law—whether the clause was in fact valid.[80] Instead, the Court remanded the case to the district court to determine the “appropriate effect” of the forum-selection clause under Section 1404(a).[81] In other words, the clause operated as one of several factors in the Section 1404(a) calculus—meaning even an invalid clause could weigh in favor of transfer.[82]

Dissenting, Justice Scalia argued that the majority’s analysis in Stewart “begs the question: what law governs whether the forum-selection clause is a valid or invalid allocation of any inconvenience between the parties.”[83] A clause that is invalid under state law “cannot be entitled to any weight in the Section 1404(a) determination.”[84] According to the dissent, the validity of a forum-selection clause is substantive under Erie’s twin aims because it both encourages forum shopping and facilitates the inequitable administration of the laws.[85] State law should thus govern the validity of a forum-selection clause, because the “decision of an important legal issue should not turn on the accident of diversity of citizenship.”[86]

Two differences are worth noting between Stewart and Atlantic Marine. First, in Stewart the Court held that Section 1404(a) was procedural precisely because it did “not carry with it a change in the applicable law.”[87] Citing Van Dusen, the Court reiterated that transfer under Section 1404(a) is a “federal judicial housekeeping measure.”[88] That justification is no longer as compelling, however, when transfer pursuant to a forum-selection clause does in fact lead to a change in the applicable law.[89] Second, unlike Stewart, Atlantic Marine was premised on the validity of the forum-selection clause at issue. Under the latter decision, a valid and enforceable clause has a virtually dispositive effect on the Section 1404(a) analysis.[90] Stewart, by comparison, deemed validity a “nonissue,” although it then treated the clause as only one of several factors to consider when evaluating a motion to transfer.[91]

These differences are particularly salient in light of the issues Atlantic Marine left undecided. The Court did not elaborate on the effect of an invalid forum-selection clause, nor did it specify whether state or federal law should govern the validity of a clause.[92] It also did not address whether Section 1404(a) can still properly be viewed as procedural when transfer entails a change in the applicable law.[93] How lower courts resolve these questions will be critical in complex disputes.

II. The Impact of Aggregation

Multidistrict litigation magnifies many of the issues that arise during an ordinary transfer. This Section considers how the general transfer principles apply to MDL, in which tens, hundreds, or potentially thousands of actions are consolidated in a single district for pretrial proceedings. Ultimately, the rules developed in Klaxon and Van Dusen currently work in much the same way in the multidistrict context. Because individual cases retain the choice-of-law rules of their home district, choice of law helps preserve each action’s individual character and counterbalances the pressure of aggregation.[94]

A. Consolidation and Choice of Law

The MDL statute, 28 U.S.C. § 1407, facilitates “coordinated or consolidated pretrial proceedings” for “civil actions involving one or more common questions of fact . . . pending in different districts.”[95] MDL is driven by efficiency and consistency; it avoids duplicative discovery, “prevent[s] inconsistent pretrial rulings, and . . . conserve[s] the resources of the parties, their counsel, and the judiciary.”[96] At the close of pretrial proceedings, the statute requires that each transferred action “be remanded . . . to the district from which it was transferred unless it shall have been previously terminated.”[97]

An action transferred to an MDL retains the choice-of-law rules of its transferor court under the principles of Klaxon and Van Dusen.[98] When an MDL court decides a dispositive motion or tries a case by consent, it does so under the substantive state law dictated by the choice-of-law rules of the transferor state.[99] MDL proceedings thus adhere to the policy that transfer “does not warrant a change in state choice-of-law rules.”[100] Most courts of appeals have held, however, that the MDL court should apply its own circuit’s interpretation of federal and procedural law.[101]

Precisely because actions transferred to an MDL retain their individual character, use of MDLs has increased as choice of law has emerged as a “monumental barrier to class certification” for class actions.[102] Under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 23(b)(3), common questions of law and fact must “predominate” for a court to certify a class action suit involving damages. This requirement has severely constricted the certification of nationwide class actions. A federal court sitting in diversity must apply the choice-of-law rules of the state in which it sits under Klaxon, and, depending on the case, many states’ choice-of-law rules require the application of different substantive laws to class members from different states. When this occurs, as it frequently does, “[c]ourts have reached a near-consensus that [it] renders the class uncertifiable under Rule 23(b)(3).”[103]

This barrier has pushed MDLs to the forefront of the complex litigation landscape, such that MDL has emerged as the “primary vehicle for the resolution of complex civil cases.”[104] Approximately one-third of all federal civil cases currently belong to an MDL,[105] and these proceedings have dramatically impacted the volume and distribution of cases, both nationally and in particular districts.[106] Pending civil cases increased by 15 percent in 2014, “primarily as a result of heavier multidistrict litigation caseloads.”[107] The Southern District of West Virginia, as one example, “reported an increase of more than 25,000 multidistrict litigation cases involving pelvic repair system products,” fueling not only litigation in that district, but the “national growth in diversity of citizenship filings as well.”[108]

Although MDL actions retain their individual character, the impact of consolidation is still significant. The statute envisions MDL as “a sort of way-station at which the preliminary aspects of the litigation can be” resolved before cases are remanded “for ultimate resolution.”[109] In reality, however, the majority of cases transferred pursuant to Section 1407 are resolved within the MDL. As of September 30, 2015, fewer than 3 percent of actions transferred under Section 1407 had been remanded to their original districts.[110] This trend is in large part due to MDL’s role as a powerful catalyst for global settlement. “By virtue of the temporary national jurisdiction conferred upon” the MDL court, the MDL judge “is uniquely situated to preside over global settlement negotiations.”[111] Rather than serving solely as a “discovery crucible,” as was perhaps originally envisioned, the MDL court plays a critical role in resolving aggregate litigation as the “centralized forum” for a dispute.[112]

B. Not Whether, But Where

The Judicial Panel on Multidistrict Litigation (“the Panel”) is responsible for coordinating MDL proceedings. The job of the Panel is two-fold: “to (1) determine whether civil actions pending in different federal districts involve one or more common questions of fact such that the actions should be transferred to one federal district for coordinated or consolidated pretrial proceedings; and (2) select the judge or judges and court assigned to conduct such proceedings.”[113] The Panel may act either on its own or in response to a motion for consolidation filed by a party.[114] By statute, the Panel consists of seven circuit and district judges selected by the Chief Justice of the United States, no two of whom may be from the same circuit.[115] A majority of four judges is required for the Panel to act.[116]

By the time a case reaches the Panel, consolidation is often “all but a foregone conclusion,” and the critical question “is not whether, but where.”[117] Because the Panel may transfer the pending actions “to any district,” Section 1407 provides significant flexibility.[118] Under the statute, the Panel has “broad powers to transfer . . . without consideration for personal jurisdiction over the parties and without having to meet the venue requirements of 28 U.S.C. § 1404.”[119] Recognizing both this flexibility and the importance of the Panel’s decision, parties advocate vigorously for their preferred district.[120] In addition to concerns regarding convenience and efficiency, parties consider the choice-of-law implications of the Panel’s decision. Although the choice-of-law rules of the transferor court will govern the applicable state law, variations in a circuit’s interpretation of federal or procedural law are often critical.[121]

The Panel considers a variety of factors when selecting an MDL court and judge. This step “is often the most difficult decision the Panel faces,” particularly given the absence of statutory guidance on where a case should be consolidated.[122] “The difficulty can arise from an abundance of good options; [sic] the absence of them, or from tactical differences among the parties, even among parties ostensibly on the same side.”[123] Whether a particular factor is relevant depends on context, but factors the Panel might consider include “the location of related grand jury proceedings, the existence of a qui tam action predicated on the same facts as those at issue in the MDL, the possibility of coordination with related state court proceedings, the location of the first-filed action, and the location of a majority of the actions.”[124] The importance of geography varies depending on the particulars of a case and the location of evidence and witnesses.[125] The selection of the MDL judge similarly hinges on a rotating set of considerations that will vary in importance depending on the case.[126] Among other factors, the Panel considers a judge’s experience, both with the specific proceeding and with the MDL process more generally, a judge’s existing caseload, and the “willingness and motivation” of a judge to manage an MDL docket.[127] Overall, the decision is an open-ended evaluation involving “considerable discretion and intuition.”[128]

Although a party might hope to avoid this uncertainty through the use of a forum-selection clause, such a clause does not limit the Panel’s authority to select an MDL court. Because Section 1407(a) provides that cases may be consolidated “in any district,”[129] the Panel has consistently held that it is not required to abide by the terms of a forum-selection clause. In In re Medical Resources Securities Litigation, the Panel explained that “contractual forum selection clauses do not limit the Panel’s authority with respect to the selection of a transferee district.”[130] Similarly, in In re Disposable Contact Lens Antitrust Litigation, the Panel rejected a defendant’s argument that the collection of actions in which the defendant was involved had to be transferred to the Northern District of California per the parties’ forum-selection clause.[131]

The same is true for orders transferring “tag-along” actions filed after the consolidation of an existing MDL. In its transfer order consolidating two cases with a preexisting MDL in Aleman v. Park West Galleries, Inc. (In re Park West Galleries, Inc.), the Panel reiterated that “[w]hen civil actions satisfy the criteria set forth in 28 U.S.C. § 1407(a), the statute authorizes the Panel to centralize those actions (as well as any subsequently identified tag-along actions) in ‘any district.’”[132] The In re Park West MDL, located in the Western District of Washington, involved allegations that the defendants had sold worthless art at auctions on cruise ships and in other private sales through the use of fraudulent appraisals and documentation.[133] In opposing the transfer, defendant Royal Caribbean Cruises argued that the actions were governed by a contract in the plaintiffs’ cruise tickets, which required that any litigation take place in Florida.[134] The Panel dismissed this argument and transferred the actions to Washington, again reiterating that its authority to select a transferee district was not restricted by the parties’ forum-selection clause.[135]

In addition to being correct as a matter of statutory interpretation, the Panel’s conclusion makes sense as a policy matter. The interests of the justice system weigh heavily against allowing parties to write their own rules of dispute resolution in a massive, consolidated action. If a forum-selection clause were given the same presumptive power under Section 1407(a) that the Supreme Court has held it is owed under Section 1404(a),[136] then the Panel would be unable to consider, for example, the status of a particular court’s docket or the practicalities of locating an MDL in a particular district. And in MDLs involving multiple defendants, only some of whom are parties to a forum-selection clause, strict adherence to the clause might result in severing a subset of the actions—negating the efficiency and consistency that would otherwise be produced by that MDL.[137] Enforcing a forum-selection clause would thus compromise the ultimate goal of selecting an MDL court to “promote the just and efficient” resolution of such actions.[138] As it has determined, the Panel should instead have the latitude to select the most appropriate court.

C. Forum-Selection Clauses and Multidistrict Litigation

Because a forum-selection clause does not—and should not—dictate the location of an MDL, it might seem that these clauses simply play no role in the MDL process. It is still possible, however, for a forum-selection clause to guide an MDL. First, for a case that progresses beyond pretrial proceedings, a clause might be enforced at that point. Further, a forum-selection clause might control the choice-of-law rules applicable in a particular MDL.

A defendant can move to enforce a forum-selection clause when a case falls into the small percentage of actions remanded following pretrial proceedings. As the Panel explained in In re Park West, “[i]t also bears noting that because Section 1407 transfer is for pretrial purposes only, our denial of this motion to vacate in no way precludes Royal Caribbean from seeking enforcement of the forum selection clauses for purposes of trial.”[139] But even following pretrial proceedings, transfer is not a given. At least one MDL court has declined to enforce a forum-selection clause where public interest factors weighed in favor of keeping the case in the district in which it was originally filed.[140] The litigation, which involved allegations of price fixing for electronic flat-panel displays, began with twenty actions pending in five separate districts that were consolidated in the Northern District of California.[141] The relevant actions were filed in the Northern District of California, but an applicable forum-selection clause required that litigation proceed in South Dakota.[142] The defendants did not challenge the location of the MDL court or propose South Dakota as a potential site for centralization.[143] Instead, the defendants requested that the MDL court transfer their cases to South Dakota once pretrial proceedings had concluded on the basis that the actions “should have been brought [there] originally.”[144]

Even though the clause was valid, the court held that enforcing the clause “would contravene the federal policy in favor of efficient resolution of controversies.”[145] In particular, because the clause covered only a subset of the purchases at issue, transferring the actions would have required that the plaintiffs’ claims against the relevant defendants “be tried separately from its substantially similar claims against the other defendants.”[146] The court did not cite Atlantic Marine, despite the defendants’ raising it in their brief,[147] instead noting that it would be “needlessly inconvenient and burdensome” to transfer only those claims governed by the forum-selection clause.[148] Thus, the court explained that “the public interest would be best served by keeping” those actions in the Northern District of California following pretrial proceedings.[149]

Putting aside what might happen in a rare instance of remand, a forum-selection clause might also impact the MDL court’s choice-of-law analysis during pretrial proceedings themselves. When a plaintiff files an action in the venue dictated by a forum-selection clause, the transferor court and the contractually identified court are one and the same. As a result, the MDL court can abide by both Van Dusen and the parties’ contract by applying the choice-of-law rules of the transferor court. The calculus is more complicated, however, when the plaintiff files in a venue other than that designated by the forum-selection clause. Once the case is consolidated in an MDL, three potential jurisdictions are involved: the transferor court where the action was originally filed, the MDL court that is adjudicating the MDL, and the venue identified in the forum-selection clause. The MDL court can then theoretically apply the choice-of-law rules of its own state, the transferor state, or, as suggested by Atlantic Marine, the contractually selected state.

Courts that have addressed this question have generally applied the choice-of-law rules of the state identified in the parties’ contract.[150] In Anwar v. Fairfield Greenwich, Ltd., the court applied Florida law to an action filed in California that was transferred to New York as part of an MDL.[151] The parties’ contract stated that any litigation “shall be governed by and construed in accordance with the laws of the State of Florida.”[152] In response to the plaintiff’s argument that California law should govern her claim, the MDL court found that she made “no persuasive argument why this provision should be disregarded.”[153] Similarly, in Refco Inc. Securities Litigation v. Aaron (In re Refco Inc. Securities Litigation), the plaintiffs argued that their tort claims were governed by the laws of New Jersey, the state in which their actions were originally filed before being transferred to an MDL in New York.[154] The court disagreed and enforced the parties’ choice-of-law clause, which provided for the application of New York law.[155] Notably, though, the court first applied New Jersey law to determine whether the choice-of-law provision was “sufficiently broad to encompass contract-related tort claims” like those at issue in the case.[156]

In sum, although a forum-selection clause does not control the location of an MDL, courts have looked to parties’ contractual agreements to determine which choice-of-law rules should govern. The next Section discusses the implications of this approach and the complications of combining aggregate proceedings with private litigation agreements.

III. Multidistrict Litigation Following Atlantic Marine

Under Atlantic Marine, a valid forum-selection clause is largely dispositive of where and under which law an ordinary case will be heard.[157] Absent “extraordinary circumstances,” a court must grant a motion to enforce a forum-selection clause under Section 1404(a).[158] And, following transfer, the transferee court must apply the choice-of-law rules of its own state rather than those of the transferor state.[159] Accordingly, a forum-selection clause selects not just the forum, but the applicable choice-of-law rules as well.[160]

As explained above, although a forum-selection clause does not control the location of an MDL, there is a potentially large opening for Atlantic Marine to impact MDL in the context of choice of law. Despite this opening, this Section argues that a forum-selection clause should not govern choice of law in an MDL proceeding. Allowing a forum-selection clause to dictate choice of law might create outcomes that would not exist absent the MDL, in violation of both Erie and general principles of complex litigation. Doing so would also increase the degree of aggregation present in an MDL proceeding without a concomitant increase in the due process protections available to plaintiffs. As a result, at least prior to a case’s being remanded, the MDL court should apply the choice-of-law rules of the transferor state, forum-selection clause notwithstanding.

A. The Reach of Atlantic Marine

Atlantic Marine does not directly apply to MDL, which is governed by Section 1407 rather than Section 1404. As the Fifth Circuit explained, “[s]trictly speaking, Atlantic Marine does not implicate transfer decisions by the Panel on Multidistrict Litigation. Those decisions are made pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1407, while Atlantic Marine, by its terms, only speaks to transfer motions brought under section 1404(a).”[161] Because Section 1407(a) specifies that an action can be transferred to “any district,”[162] a forum-selection clause does not control the location of an MDL.[163] By comparison, Section 1404(a) allows for transfer only to any district or division where the action “might have been brought or . . . to which all parties have consented.”[164] But although a forum-selection clause does not control the location of an MDL, an MDL court might be inclined to extend Atlantic Marine to its choice-of-law analysis. The language of the relevant statutes, the underlying reasoning of the decision, and the potential simplification of the choice-of-law analysis all arguably support applying Atlantic Marine to the MDL context.

First, Section1407(a) and Section 1404(a) outline largely identical factors for courts to consider when deciding whether to transfer an action. “[B]ecause Congress set similar considerations to guide treatment of transfer motions in both contexts,” Atlantic Marine might be seen “to inform[] MDL practice.”[165] Specifically, Section 1407(a) provides that an MDL is proper where it “will be for the convenience of parties and witnesses and will promote the just and efficient conduct of such actions.”[166] Section 1404(a) similarly states that a district court may transfer a standalone civil action “for the convenience of parties and witnesses, in the interest of justice.”[167] In accordance with the language of the respective statutes, courts deciding a motion under either Section 1404(a) or Section 1407(a) are driven by the same set of motivations: the interests of the parties, the witnesses, and the justice system. Accordingly, to the extent a forum-selection clause is controlling under Section 1404(a), it might similarly be seen as controlling under Section 1407(a).

Further, following “Atlantic Marine, MDL courts might decide that . . . [a] plaintiff’s forum shopping is inappropriate and warrants a departure from the Van Dusen rule.”[168] Atlantic Marine marks a shift from the Supreme Court’s substantial tolerance of horizontal forum shopping. In prior opinions, the Court had accepted that prioritizing vertical uniformity created an opening for interstate forum shopping.[169] But the Court narrowed this acceptance in Atlantic Marine, holding that the contractually selected court should apply its own choice-of-law rules, in part because “§ 1404(a) should not create or multiply opportunities for forum shopping.”[170] Currently, plaintiffs, particularly those in tag-along MDLs, “are able to take advantage of forum shopping to obtain better law with little impact if the chosen forum is inconvenient.”[171] Because a tag-along action will be transferred to the MDL court almost immediately, the filing is essentially an opportunity for plaintiffs to select their preferred choice-of-law rules.[172] A court that desired to preclude this benefit could do so by applying the choice-of-law rules of the contractually selected state instead. In addition, the goal of giving parties the benefit of their bargain could be at least partially fulfilled by the MDL court’s applying the choice-of-law rules of the forum identified in the contract.

Finally, enforcing a forum-selection clause would simplify the MDL court’s potentially complex choice-of-law analysis.[173] Rather than ascertaining and then applying the choice-of-law rules of a disparate set of transferor courts, the MDL court could apply the choice-of-law rules of the contractually selected venue to all of the actions governed by the forum-selection clause. Doing so “would be a significant departure from the dogma that an MDL transfer is only for ‘pretrial proceedings,’ but one could imagine a lower court charting such a course in an effort to simplify its choice-of-law task.”[174] An MDL court could thus reasonably argue that extending Atlantic Marine is warranted to increase both efficiency and consistency.

B. Maintaining Choice of Law Particularity

Despite these justifications, Atlantic Marine should not control choice of law in an MDL. Just as a forum-selection clause does not mandate the site for consolidation, it similarly should not dictate the applicable choice-of-law rules. First, abiding by a forum-selection clause would in some cases lead to outcomes that would not have existed absent the MDL. When that occurs, a party’s substantive rights have been impacted both by the “accident” of diversity jurisdiction—which allows for a case’s inclusion in an MDL—and the fact of consolidation. Moreover, enforcing a forum-selection clause in an MDL proceeding would aggravate due process concerns already inherent in aggregate litigation. MDL courts should instead apply the choice-of-law rules of the transferor state, meaning a forum-selection clause will not have any impact prior to a case’s being remanded at the close of pretrial proceedings.

1. Creation of Different Outcomes

Atlantic Marine assumes a valid forum-selection clause.[175] When a forum-selection clause is valid and enforceable, it governs in all but “extraordinary circumstances.”[176] As discussed above, this emphasis on validity is a shift from the Supreme Court’s earlier decision in Stewart Organization v. Ricoh Corp., in which the Court declined to address validity and instead considered the existence of a forum-selection clause as one factor among many under Section 1404(a).[177] Despite this shift, Atlantic Marine did not resolve a split among the courts of appeals regarding whether federal or state law governs the validity of a forum-selection clause in a diversity action.[178] Because the validity of a forum-selection clause is often at issue, this split has the potential to lead to disarray in the MDL context.[179]

Most federal courts apply the law of their own circuit to assess the validity of a forum-selection clause, leading to two potential areas of incongruity.[180] First, the circuits disagree over whether state or federal law governs the validity of a clause.[181] Second, even where courts agree that state law governs the validity of a clause, there might be a disagreement between the laws of the states in which the transferor and MDL courts sit.[182] In either scenario, under Atlantic Marine a case might be decided differently because of its inclusion in an MDL.

Assume Atlantic Marine governs choice of law in MDL proceedings, and consider a situation in which a transferor court in State A and an MDL court in State B disagree over whether state or federal law should determine the validity of a forum-selection clause identifying State C as the transferee court. Suppose the district court in State A would look to state law to determine the validity of a forum-selection clause, and under State A’s law the clause is invalid. Then suppose the district court in State B would instead look to federal law, and under federal law the clause is valid. This scenario is illustrated in scenario (1) below. In an ordinary proceeding, the forum-selection clause would be held invalid, and the case would be adjudicated in State A pursuant to State A’s choice-of-law rules. Within an MDL, however, the clause would be enforced, and the MDL court would apply the choice-of-law rules of State C, the state identified in the forum-selection clause.

The same is also true in reverse, illustrated in scenario (2) below. There, the discrepancy between state and federal law creates different outcomes when the original jurisdiction would enforce the clause and the MDL court would not. Suppose State A looks to federal law to assess the validity of a forum-selection clause, and the clause is valid under federal law. In an ordinary proceeding, State A would transfer the action to State C, which would apply State C’s choice-of-law rules. Then suppose State B would invalidate the clause under State B’s law, such that State B would apply State A’s choice-of-law rules within the MDL. In both scenarios, transfer to an MDL might effect a change in the governing choice of law because of a disagreement between the transferor court and the MDL court as to the validity of a forum-selection clause. Although a case is only transferred to an MDL for pretrial proceedings, such proceedings can include substantive motions for which a change in the governing law might prove dispositive.

These scenarios assume that the forum-selection clause is valid under federal law and invalid under state law. This assumption accords with likely outcomes on the ground: forum-selection clauses are generally enforceable under federal law,[183] but they are frequently disfavored under state law.[184] Thus, a disagreement between the transferor court and the MDL court as to which law, state or federal, governs the validity of a forum-selection clause will frequently lead to different outcomes.

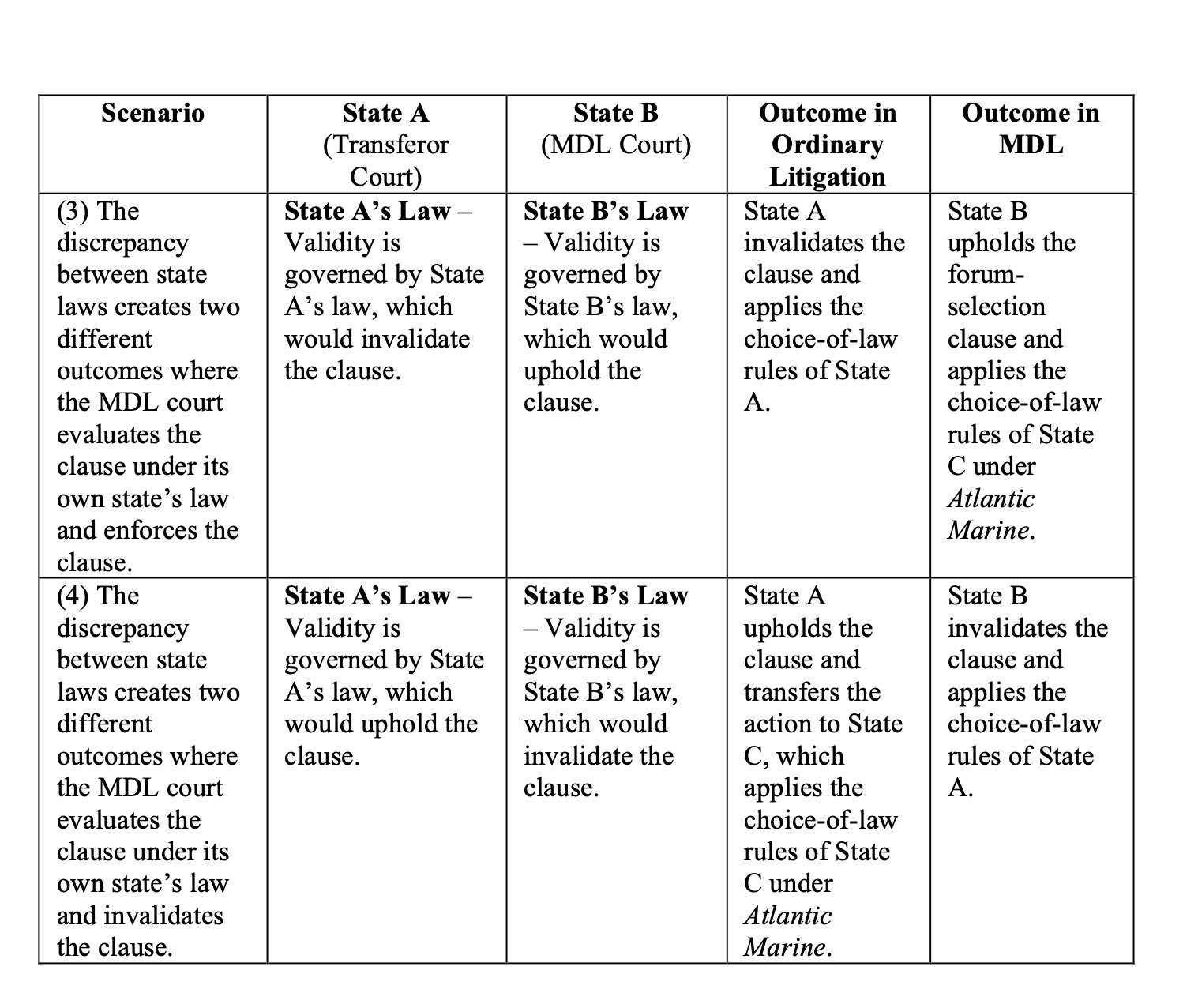

Even where the federal courts in State A and State B both look to state law to determine the validity of a clause, there is the separate potential for disagreement if the state laws themselves diverge. Suppose that State A would invalidate a clause while State B would uphold it. As illustrated in scenario (3) below, absent the MDL, the clause would be struck down and the case would be adjudicated pursuant to the choice-of-law rules of State A. Within the MDL, however, State B would enforce the clause and apply the choice-of-law rules of State C, the state identified in the forum-selection clause. The same problem also arises in reverse. In scenario (4), assume State A would uphold the clause while State B would invalidate it. Absent the MDL, the case would be transferred to State C, which would apply its own choice-of-law rules. Within the MDL, State B would invalidate the clause and instead apply the choice-of-law rules of State A. Both scenarios again create the possibility of an outcome that would exist in an MDL, but not in an ordinary proceeding.

These examples illustrate how inclusion in an MDL might lead to a different outcome in a case. When it does, the parties’ substantive rights are impacted by two “accidents”: the accident of diversity jurisdiction—which is the only way a case governed by state substantive law might find itself in an MDL—and, relatedly, the accident of consolidation. These are “accidents” in the sense that they are not tied to the merits of the underlying action, and thus should not impact the disposition of the case.[185]

Atlantic Marine creates the possibility that the outcome of a case might hinge on the presence of diversity jurisdiction. A typical Section 1404(a) transfer avoids this problem under Erie because the transferee court applies the choice-of-law rules of the state in which the transferor court sits.[186] But where a forum-selection clause controls, enforcing the clause under Atlantic Marine “will both effect a geographic transfer of the case and require application of the transferee state’s choice-of-law rules”—“even in cases in which the state in which the [transferor] court sits would not enforce the forum-selection clause.”[187]

Although this possibility exists in ordinary cases as well, its effect is compounded in a complex proceeding. With an ordinary transfer, diversity jurisdiction might lead to a different outcome where a federal court enforces a clause that its counterpart state court would not uphold. But the validity of the clause is still determined by the federal court in the state in which the case was filed. Because the majority of courts apply their own law to assess validity, the plaintiff still retains a degree of control.[188] In an MDL, by comparison, the law which governs the validity of a forum-selection clause is determined by the MDL court—a court which might have little to do with a particular action beyond serving as the forum for centralization. Moreover, where the transferor court and the MDL court disagree over validity, the MDL creates the possibility for different outcomes even where diversity jurisdiction alone would not. Once consolidation leads to a change in choice of law and, potentially, the governing substantive law, the MDL proceeding has lost a critical feature that allowed it to exist as a collection of individual cases rather than as a single mass action.

An MDL court can avoid this possibility, however, by applying the choice-of-law rules of the transferor court. Abiding by the choice-of-law principle outlined in Van Dusen will allow Section 1407 to continue to operate as, if not quite a “housekeeping” measure, at least a procedural mechanism that does not impact the substantive law governing pretrial proceedings in a particular case. Under this approach, a case’s inclusion in an MDL will not lead to a different outcome based on a change in choice of law. Accordingly, an MDL court should apply the choice-of-law rules of the transferor court—forum-selection clause notwithstanding.

2. Due Process and the Pressure of Aggregation

All civil actions implicate the parties’ due process rights: the plaintiffs in their claim, and the defendants in the property they are seeking to protect.[189] In simplest terms, due process exists to ensure that no one is “personally bound until he has had his day in court.”[190] Protecting this “day-in-court” ideal is challenging in a consolidated action, because aggregation is in tension with ensuring an individual adjudication for each party.[191] As in a class action, MDL claims “lose their individual identities when they are clumped together.”[192] In comparison to class actions, however, MDL proceedings have far fewer procedural safeguards to provide the “minimal protection” of this day-in-court ideal.[193] The lack of procedural safeguards might not create much cause for concern if the majority of MDL actions returned to their home districts at the end of the pretrial phase. But because “transfer effectively amounts to the end of the road for the overwhelming majority of cases,” the treatment of a case within the MDL is itself critical.[194]

In particular, because the parties in an MDL proceeding are generally under significant pressure to settle, careful attention should be paid to the settlement process.[195] Unlike in a class action, in an MDL there is no certification hurdle for the parties to clear.[196] Once a case has been consolidated, the next question is whether the proceeding will lead to some form of collective settlement. MDL proceedings thus encourage the same global settlement process that might occur in the context of a class action were it not for differences in the applicable state laws.[197] Many judges overseeing MDL proceedings recognize that “the centralized forum created by the MDL Panel truly provides a ‘once-in-a-lifetime’ opportunity for the resolution of mass disputes by bringing similarly situated litigants from around the country, and their lawyers, before one judge in one place at one time.”[198] As a result, some MDL judges view their objective as facilitating global settlement, rather than conducting pretrial proceedings.[199]

Glossing over the differences among individual actions, settlement is “determined on a one-size-fits-all collectivist basis, helping those plaintiffs with weaker individual cases while harming those plaintiffs” with stronger ones.[200] It is challenging—if not impossible—for plaintiffs to evaluate their recovery under a proposed settlement in relation to the strength of their particular claims. [201] And although parties retain their own attorneys, the collective settlement risks “compromis[ing] the relationship between [the] individual attorney and his client.”[202] In evaluating a settlement, an attorney may be tempted to consider the impact on his or her fee of the client’s joining the settlement.[203] Further, unless a party’s individual attorney happens to be part of the MDL steering committee, the party will not have individual representation within the group drafting the terms of the settlement.[204]

When individual actions retain their own choice-of-law rules—and thus their own substantive law—it helps counteract this collective settlement pressure. Differences in choice of law aid in distinguishing cases from one another, thus reducing the pressure to settle. Once a forum-selection clause governs all of the actions, however, this distinguishing factor disappears. When crafting the settlement, the parties can avoid thorny choice-of-law issues that might otherwise highlight differences in the viability and value of individual claims. And because the same substantive law will likely apply to all of the individual actions, it is far easier for the steering committee to draft a global settlement agreement.[205]

Although this might be a positive outcome if the only goal of MDL were facilitating settlement, making it easier to settle a case also makes it easier to run roughshod over parties’ due process rights. This is particularly true when the applicable forum-selection clause is invalid under the laws of certain states. If Atlantic Marine is extended to the MDL context and the MDL court determines that a forum-selection clause is valid, it must apply the transferee state’s choice-of-law rules, regardless of whether the clause is enforceable under the laws of the transferor state.[206] Not only does enforcing a forum-selection clause substantially increase the pressure to settle, then, but it does so where only some of the parties might be bound by the clause dictating the governing law. And even if the enforceability of the clause could later be litigated more vigorously on remand, “later never comes, and never will, because the cases always settle first.”[207] Enforcing a forum-selection clause in the MDL context would also give the party that drafts the contract outsize influence over the collective dispute, thus incentivizing a race-to-the-bottom in selecting the governing law. Although this is true to a degree with any forum-selection clause, the possibility that the clause will apply across the board in a mass litigation makes the incentive that much stronger.

Because enforcing a forum-selection clause will aggravate the due process concerns already inherent in multidistrict litigation, courts should decline to enforce such clauses during pretrial proceedings. In the rare situation where a case is remanded to its original district, the parties can then contest whether the forum-selection clause should govern the litigation. Prior to that point, however, the MDL court should resist any changes that overlook differences among the individual actions and increase the pressure to settle.

Conclusion

In general, treating a complex case the same as an ordinary case preserves the parties’ substantive rights and ensures that a case does not change in response to aggregation. With respect to forum-selection clauses, however, crafting an MDL-specific rule in fact helps preserve the individual character of each underlying action. Even when a forum-selection clause would govern an ordinary proceeding, allowing the clause to control choice of law for all of the pending actions in an MDL essentially converts a collection of individual cases into one mass action. Given the lack of procedural protections available in MDL proceedings, this conversion creates significant due process concerns for a tool that governs one-third of the federal courts’ current caseload. Moreover, because of disagreement among courts as to which law governs the validity of a forum-selection clause, introducing an MDL court into the choice-of-law calculus might lead to the application of different choice-of-law rules, and thereby different outcomes. As a result, courts should decline to extend Atlantic Marine to the MDL context, and should instead continue to apply the transferor state’s choice-of-law rules, regardless of the presence of a forum-selection clause.

Copyright © 2018 California Law Review, Inc. California Law Review, Inc. (CLR) is a California nonprofit corporation. CLR and the authors are solely responsible for the content of their publications.

Jordan F. Bock, Law Clerk to the Honorable Vince Chhabria, United States District Court for the Northern District of California; J.D. 2017, University of California, Berkeley, School of Law. I wish to thank Professor Andrew D. Bradt for his continued encouragement and guidance with this project and University of Pennsylvania Law Professor Stephen B. Burbank for reviewing an earlier draft. Special thanks as well to Dawn and Steven Bock for their helpful feedback, and to the editors of the California Law Review for their careful and thoughtful work. This Note is based solely on information available in the public record and reflects no one’s views but my own.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.15779/Z38BG2H979.

- Erie R.R. v. Tompkins, 304 U.S. 64, 78–80 (1938). ↑

- Klaxon Co. v. Stentor Elec. Mfg. Co., 313 U.S. 487, 496 (1941). ↑

- Van Dusen v. Barrack, 376 U.S. 612, 639 (1964). ↑

- See Klaxon, 313 U.S. at 496 (noting that, under Erie, “the accident of diversity of citizenship” should not “constantly disturb equal administration of justice in coordinate state and federal courts sitting side by side”). ↑

- 28 U.S.C. § 1407(a) (2018). ↑

- See Andrew D. Bradt, The Shortest Distance: Direct Filing and Choice of Law in Multidistrict Litigation, 88 Notre Dame L. Rev. 759, 784 (2012) (“Recent empirical work by the Federal Judicial Center reveals that one third of all civil cases in the federal courts right now are part of a pending MDL.”); see also Andrew S. Pollis, The Need for Non-Discretionary Interlocutory Appellate Review in Multidistrict Litigation, 79 Fordham L. Rev. 1643, 1667 (2011) (“[B]y 2008, the 102,545 actions pending in MDLs constituted more than a third of all federal civil cases pending in that year . . . .”). ↑

- For example, in 2017 the House of Representatives passed the Fairness in Class Action Litigation and Furthering Asbestos Claim Transparency Act. Among other changes, the Act imposes an ascertainability requirement for class certification and allows a direct appeal, as of right, from an order certifying or refusing to certify a class action. H.R. 985, 115th Cong. (1st Sess. 2017). ↑

- 15 Charles Alan Wright et al., Federal Practice and Procedure § 3866 (3d ed. 2007). ↑

- Atl. Marine Constr. Co. v. U.S. Dist. Court, 134 S. Ct. 568, 582–83 (2015). ↑

- Id. at 583. ↑

- See Andrew D. Bradt, Atlantic Marine and Choice-of-Law Federalism, 66 Hastings L.J. 617, 619 (2015) (“Atlantic Marine therefore ensures that a contractual forum-selection clause is also a ‘choice-of-law rules selection’ clause. That is, by choosing a forum in a contract, the parties also choose that forum’s choice-of-law rules, and therefore, often that forum’s law.”). ↑

- See, e.g., In re Disposable Contact Lens Antitrust Litig., 109 F. Supp. 3d 1369, 1371 (J.P.M.L. 2015). ↑

- See Kevin M. Clermont, Governing Law on Forum-Selection Agreements, 66 Hastings L.J. 643, 649 (2015) (explaining that “[a]lmost all American courts apply their own law, the lex fori” to determine the validity of a forum-selection clause). ↑

- See Larry Kramer, Choice of Law in Complex Litigation, 71 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 547, 549 (1996) (“The argument in a nutshell is this: Because choice of law is part of the process of defining the parties’ rights, it should not change simply because, as a matter of administrative convenience and efficiency, we have combined many claims in one proceeding; whatever choice-of-law rules we use to define substantive rights should be the same for ordinary and complex cases.”). ↑

- See, e.g., Bradt, The Shortest Distance, supra note 7, at 760 (“Aggregation seeks sameness, while choice of law focuses on particularity.”); Kramer, supra note 15, at 579 (“Choice of law defines the parties’ rights. States differ about what those rights should be. Such differences are what a federal system is all about. They are not a ‘cost’ of the system; they are not a flaw in its operation. They are its object, something to be embraced and affirmatively valued.”). ↑

- Kramer, supra note 15, at 549. ↑

- Van Dusen v. Barrack, 376 U.S. 612, 639 (1964); see also Klaxon Co. v. Stentor Elec. Mfg. Co., 313 U.S. 487, 496 (1941); Ferens v. John Deere Co., 494 U.S. 516, 523 (1990). ↑

- Atl. Marine Constr. Co. v. U.S. Dist. Court, 134 S. Ct. 568 (2013). ↑

- Id. at 581, 583. ↑

- Irving Younger, What Happened in Erie, 56 Tex. L. Rev. 1011, 1014 (1978) (“Tompkins was a citizen of Pennsylvania. The Erie Railroad was a New York corporation. The matter in controversy—damages for a lost right arm—certainly exceeded $3000. This was diversity jurisdiction, and the case would lie in a United States district court.”). ↑

- Id. ↑

- Kermit Roosevelt III, Choice of Law in Federal Courts: From Erie and Klaxon to CAFA and Shady Grove, 106 Nw. U.L. Rev. 1, 6 (2012) (noting that most states employed a negligence standard). ↑

- Younger, supra note 21, at 1016. ↑

- Id.; see also Swift v. Tyson, 41 U.S. 1 (1842). Federal court in Pennsylvania was not an option because Tompkins’s lawyers were not licensed there. Younger, supra note 21, at 1016. In addition, “the Third Circuit Court of Appeals, which included Pennsylvania, had fallen into the disagreeable habit of deferring to local law, relying less upon the ‘general’ law of Swift v. Tyson than did other circuits.” Id. ↑

- Erie R.R. v. Tompkins, 304 U.S. 64, 78 (1938). ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. at 79. ↑

- Id. at 74. ↑

- Id. at 75. ↑

- Bauer, supra note 1, at 1236. ↑

- See Klaxon Co. v. Stentor Elec. Mfg. Co., 313 U.S. 487, 496 (1941). ↑

- Bauer, supra note 1, at 1274 (“[T]he possibility that different legal rules will prevail” in different states “is essentially the product of our federal system, which contemplates that each state remains free, subject only to constitutional constraints, to shape its law in a variety of ways.”). ↑

- See Roosevelt, supra note 23, at 6. ↑

- The Court could have addressed the choice-of-law question in a decision issued the same day as Erie, but it declined to reach the issue. See Ruhlin v. N.Y. Life Ins. Co., 304 U.S. 202, 208 n.2 (1938). ↑

- Bradt, The Shortest Distance, supra note 7, at 769 (“Prior to Erie, choice of law was considered a matter of federal common law in diversity cases.”). ↑

- See Sampson v. Channell, 110 F.2d 754, 761 (1st Cir. 1940) (noting that if the federal courts are free to follow their own choice-of-law rules, “then the ghost of Swift v. Tyson . . . still walks abroad, somewhat shrunken in size, yet capable of much mischief”). ↑

- Klaxon Co. v. Stentor Elec. Mfg. Co., 313 U.S. 487, 494–95 (1941). ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. at 495–96 (“Application of the New York statute apparently followed from the court’s independent determination of the ‘better view’ without regard to Delaware law, for no Delaware decision or statute was cited or discussed.”). ↑

- Id. at 496. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. (“Whatever lack of uniformity this may produce between federal courts in different states is attributable to our federal system, which leaves to a state, within the limits permitted by the Constitution, the right to pursue local policies diverging from those of its neighbors. It is not for the federal courts to thwart such local policies by enforcing an independent ‘general law’ of conflict of laws.”). ↑

- Id. at 498. ↑

- Id. at 496. ↑

- See, e.g., Kramer, supra note 15, at 579. ↑

- Under 28 U.S.C. § 1404(a), an action may be transferred to a different district “[f]or the convenience of parties and witnesses, in the interest of justice.” A court evaluating a transfer under § 1404(a) considers both the parties’ private interests and the public-interest considerations attendant to the case. Atl. Marine Constr. Co. v. U.S. Dist. Court, 134 S. Ct. 568, 581 (2013). Public-interest factors include “the administrative difficulties flowing from court congestion; the local interest in having localized controversies decided at home; [and] the interest in having the trial of a diversity case in a forum that is at home with the law.” Id. at 581 n.6 (quoting Piper Aircraft Co. v. Reyno, 454 U.S. 235, 241 n.6 (1981)). Private-interest factors include the “relative ease of access to sources of proof; availability of compulsory process for attendance of unwilling, and the cost of obtaining attendance of willing, witnesses . . . and all other practical problems that make trial of a case easy, expeditious and inexpensive.” Id. (quoting Piper Aircraft Co., 454 U.S. at 241 n.6). ↑

- Van Dusen v. Barrack, 376 U.S. 612 (1964). ↑

- Id. at 613. ↑

- Id. at 614. ↑

- Id. at 627–28. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. at 636–37. ↑

- Id. at 639. ↑

- Id. at 634. ↑

- Ferens v. John Deere Co., 494 U.S. 516, 523 (1990). Note, however, that this decision has its own concerning implications under Erie. See Bradt, The Shortest Distance, supra note 7, at 779 n.115 (“Ferens, by allowing plaintiffs to file in one far-flung forum and seek a transfer, allows a result unattainable in state courts—the ability to achieve both a nearby forum and a distant forum’s choice-of-law rules.”). ↑

- Ferens, 494 U.S. at 523. ↑

- Atl. Marine Constr. Co. v. U.S. Dist. Court, 134 S. Ct. 568 (2013). A forum-selection clause is a “contractual provision in which the parties establish the place (such as the country, state, or type of court) for specified litigation between them.” Forum-Selection Clause, in Black’s Law Dictionary (Bryan A. Garner ed., 10th ed. 2014). ↑

- Atl. Marine, 134 S. Ct. at 575. ↑

- United States ex rel. J-Crew Mgmt., Inc. v. Atl. Marine Constr. Co., No. A-12-CV-228-LY, 2012 WL 8499879, at *1 (W.D. Tex. Aug. 6, 2012). ↑

- Atl. Marine, 134 S. Ct. at 576. ↑

- Id. at 576–77. ↑

- Id. at 576 n.1. Venue was proper “because the subcontract at issue in the suit was entered into and was to be performed in” the Western District of Texas. Id.; see also 28 U.S.C. § 1391(b)(2) (2018). ↑

- As discussed below, this is a significant assumption to make. ↑

- Atl. Marine, 134 S. Ct. at 581. ↑

- Id. (“Only under extraordinary circumstances unrelated to the convenience of the parties should a § 1404(a) motion be denied.”). ↑

- Atl. Marine, 134 S. Ct. at 582. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. at 583; see also Bradt, Choice-of-Law Federalism, supra note 12, at 635 (explaining that, where a plaintiff files suit in “a state hostile to enforcing forum-selection clauses,” diversity jurisdiction might still lead to “a transfer to the forum chosen in the contract”—a “transfer [that] would have been impossible had the defendant been a citizen of the same state as the plaintiff, or if the defendant was a citizen of the state in which the plaintiff originally sued”). ↑

- See Bradt, Choice-of-Law Federalism, supra note 12, at 619. ↑

- Stewart Org. v. Ricoh Corp., 487 U.S. 22, 24 (1988); see Stephen E. Sachs, Five Questions After Atlantic Marine, 66 Hastings L.J. 761, 769 (2015) (explaining that Atlantic Marine partially overruled the Court’s earlier decision in Stewart by treating “as crucial” the validity of a forum-selection clause). ↑

- Stewart, 487 U.S. at 24. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. at 32. ↑

- Id. (“Section 1404(a) is doubtless capable of classification as a procedural rule, and indeed, we have so classified it in holding that a transfer pursuant to § 1404(a) does not carry with it a change in the applicable law.”). ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id.; see also Sachs, supra note 73, at 769 (noting that “the Court treated the clause merely as fodder in a standard § 1404 analysis, purportedly using the same factors as are always applied under that statute”). ↑

- See Sachs, supra note 73, at 769 (explaining that, under this approach, “[a] clause can justify transfer even if it’s wholly unenforceable under the relevant law (for missing certain formalities, involving a certain subject area, and so on), because the parties’ private expression of their venue preferences—again, taking relative bargaining power into account—is a significant factor in determining the interest of justice”) (internal citations omitted). ↑

- Stewart, 487 U.S. at 35 (Scalia, J., dissenting); see also Linda Mullenix, Another Choice of Forum, Another Choice of Law: Consensual Adjudicatory Procedure in Federal Court, 57 Fordham L. Rev. 291, 336 (1988) (“The Court incorrectly cast [Stewart] as a venue-transfer problem. Instead of asking the threshold question, whether the dispute involved contract law or venue law, the Court instead asked whether a federal statute covered the point in dispute. The obvious answer to this question—28 U.S.C. section 1404—led to the plodding, unsurprising Erie conclusion that federal venue law must control in diversity cases.”). ↑

- Stewart, 487 U.S. at 35 (Scalia, J., dissenting). ↑

- Id. at 39–40 (“With respect to forum-selection clauses, in a State with law unfavorable to validity, plaintiffs who seek to avoid the effect of a clause will be encouraged to sue in state court, and nonresident defendants will be encouraged to shop for more favorable law by removing to federal court. In the reverse situation—where a State has law favorable to enforcing such clauses—plaintiffs will be encouraged to sue in federal court. This significant encouragement to forum shopping is alone sufficient to warrant application of state law.”). ↑

- Id. ↑

- Bradt, Choice-of-Law Federalism, supra note 12, at 636. ↑

- Stewart, 487 U.S. at 32. ↑

- See Bradt, Choice-of-Law Federalism, supra note 12, at 636–37. ↑

- See Atl. Marine Constr. Co. v. U.S. Dist. Court, 134 S. Ct. 568, 581 (2013). ↑

- See Sachs, supra note 73, at 769. ↑

- Id. at 766, 769. ↑

- See Bradt, Choice-of-Law Federalism, supra note 12, at 636. ↑

- See Bradt, The Shortest Distance, supra note 7, at 791–92. ↑

- 28 U.S.C. § 1407(a) (2012). ↑

- An Introduction to the United States Judicial Panel on Multidistrict Litigation, U.S. Jud. Panel on Multidistrict Litig., (Nov. 15, 2016), http://www.jpml.uscourts.gov/sites/jpml/files/JPML-Overview-Brochure-11-15-2016.pdf [https://perma.cc/TH4Q-CLK4]. ↑

- 28 U.S.C. § 1407(a) (2018). ↑

- See, e.g., Kramer, supra note 15, at 552 n.14 (citing cases and noting that “Van Dusen itself dealt only with transfer under § 1404(a), but lower courts have extended its holding to transfers under § 1407”). ↑

- See Bradt, The Shortest Distance, supra note 7, at 793. ↑

- Id. at 779. ↑

- See, e.g., Knouse v. Gen. Am. Life Ins. Co. (In re Gen. Am. Life Ins. Co. Sales Practices Litig.), 391 F.3d 907, 911 (8th Cir. 2004) (“When a transferee court receives a case from the MDL Panel, the transferee court applies the law of the circuit in which it is located to issues of federal law.”); Menowitz v. Brown, 991 F.2d 36, 40 (2d. Cir. 1993) (“A transferee federal court should apply its interpretation of federal law, not the constructions of federal law of the transferor circuit.”); In re Korean Air Lines Disaster of Sept. 1, 1983, 829 F.2d 1171, 1176 (D.C. Cir. 1987) (holding that the MDL court is not required to apply the transferor court’s interpretation of federal law). But see Eckstein v. Balcor Film Inv’rs, 8 F.3d 1121, 1128 (7th Cir. 1993) (holding that where there is disagreement among the circuit courts, the MDL court should apply the law of the transferor forum). ↑