Discriminatory Paycheck Protection

Political lobbyists and owners of strip clubs have gone to court in recent months to get a share of the money Congress allotted to help small business owners keep their payroll flowing during the pandemic. Both groups are ineligible for the hundreds of billions of dollars offered through the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP), a forgivable loan program established in the historic Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act and administered by the Small Business Administration (SBA).

This might come as a surprise—not just that anyone should have convinced courts to second-guess the federal government’s spending choices during an emergency, but more so, that the winner would be businesses operating “only marginally” within “the outer perimeters of the First Amendment,”

Counterintuitive as these split decisions may seem, both outcomes might be correct. Seeing why, though, requires an answer to one of the most “notoriously tricky question[s] of constitutional law”

Part I of this Essay introduces one such program, the PPP, and the administrative and constitutional challenges it has triggered. Part II explores the complicated constitutional landscape these cases are forcing courts to navigate, while Part III offers a path through it, explaining why the claims of strip club owners should succeed while lobbyists’ fail. Part IV concludes with a tangent about judicial transparency that isn’t really a tangent at all: a procedural move to seal records in one of these cases shows that the SBA isn’t the only party fighting to cut off subsidies for expression it opposes.

Table of Contents Show

I. The Paycheck Protection Act and Its Challengers

The $2 trillion CARES Act, the largest stimulus package in U.S. history, allocated hundreds of billions of dollars to the Paycheck Protection Program, a loan program for businesses suffering the economic effects of the COVID-19 epidemic.

These eligibility criteria are the focus of the legal challenges now springing up around the country: a couple dozen lawsuits filed not just by political lobbyists and adult business owners, but also tribal casinos,

The bars on lobbying and prurient businesses have been in place since 1996, yet no one has challenged them before now.

Lobbyists and strip club owners disagreed—and did so more vigorously once the SBA incorporated its bars against both into the Paycheck Protection Program. The adult businesses came to court first. In a lawsuit filed in the Eastern District of Michigan in early April, DV Diamond, operator of a topless bar in Flint, claimed that its exclusion from the PPP was vague and content discriminatory (in double violation of the Free Speech Clause), as well as inconsistent with the terms of the CARES Act (in violation of the Administrative Procedure Act).

Meanwhile, in the Eastern District of Wisconsin, a pair of cases brought by owners of “gentlemen’s clubs,” mostly in Milwaukee, were combined under the name Camelot Banquet Rooms, Inc. v. U.S. Small Business Administration.

On the same day that Camelot Banquet Rooms filed its complaint, the American Association of Political Consultants (AAPC) filed suit in the District of Columbia, arguing that its members were being unconstitutionally shut out from the PPP. AAPC claims that 13 C.F.R. § 120.110(r), the bar on businesses “primarily engaged in political or lobbying activities,” places an unconstitutional condition on public funding by requiring recipients to give up their free speech rights in exchange for a subsidy, and violates equal protection by discriminating against certain businesses based on the content of their expression.

And yet that is the claim on which DV Diamond and its fellow adult businesses have prevailed in Michigan and, so far, in the Sixth Circuit.

This holding strikes me as correct. The Act makes clear that “in addition to small business concerns, any business concern, nonprofit, veterans organization, or Tribal business concern . . . shall be eligible” for PPP loans.

Congress’s decision to expand funding to previously ineligible businesses is not an endorsement or approval of those businesses. Instead, it is a recognition that in the midst of this crisis, the workers at those businesses have no viable alternative options for employment in other, favored lines of work and desperately need help.

The idea here is that the PPP was meant to keep small employers’ payrolls from drying up, not to save or promote certain types of employers themselves. The Wisconsin court relied on a similarly purposive argument when it, too, held that the SBA’s eligibility criteria exceed its statutory authority.

Other courts, however, have recently found the CARES Act’s language to be more ambiguous.

If strip clubs and lobbyists can’t count on the success of these statutory claims, they are left only with their free speech ones.

While the D.C. courts rejected AAPC’s free speech claims in fairly short order,

Have these courts just come to different conclusions about the same legal question? That would be unremarkable, given the complexity of the First Amendment issues at stake. But I want to suggest an alternative: that both decisions are right. Excluding strip clubs from funding under the PPP raises constitutional concerns that the exclusion of political lobbyists does not. In short, on their First Amendment claims, the strip clubs should win while the lobbyists lose.

Getting to that conclusion, though, requires finding a path through something of a constitutional thicket.

II. Tangled Lines of First Amendment Doctrine

The PPP challenges stand at the intersection of confusingly many lines of First Amendment doctrine: cases about government subsidies offered as awards,

It isn’t always clear, even to the Supreme Court, what doctrinal category applies in any given case.

Consider: the government subsidizes some businesses or activities but not others. It does so regularly, massively, and unproblematically, at least from a constitutional standpoint. If farmers get a subsidy but cobblers do not,

Selective subsidies for expression take many forms. The government commissions expression directly;

In short, the government has a freedom in picking and choosing what expression to subsidize that goes far beyond what the First Amendment allows when state actors try to restrict, burden, or prohibit expression.

Intuitive as this principle may be, it isn’t absolute. Equally intuitive is the notion that NEA grants cannot constitutionally be doled out only to artists who are Republicans,

The problem with these examples is that they are blatantly viewpoint discriminatory: attempts to distort public debate, either by putting a thumb on the scale or punishing those whose views the government disfavors.

But here we have to be careful, for, to a certain extent, all subsidies put a thumb on the scale—in favor of the thing subsidized, if in no other way. All subsidies can be said to discriminate in favor of the view that the thing subsidized is worthy of governmental support. The viewpoint discrimination in the examples above goes further, however. Whereas NEA grants surely endorse a pro-art viewpoint, and media exemptions in tax law reflect a belief in the value of a free press, partisan and ideological limitations on these subsidies introduce new, irrelevant or even inconsistent considerations. The political party of the artist isn’t what makes something good as art; a free press is made less free when the government targets some news outlets for disfavored treatment. Likewise, introducing topical or evaluative considerations into the periodicals postage scheme would turn that into a different program entirely. The principle here is: any discrimination involved in selective subsidies must, at the very least, be related to the point of the subsidy program.

These examples suggest another principle as well. At a certain point a subsidy program might be so big—either in terms of its scope or its importance—that to deny the subsidy to some is to target or, to use the language of the Free Speech Clause, abridge their speech.

The principle here is: the smaller the subsidy and the fewer who get it, the less can those denied the subsidy complain of unconstitutional discrimination.

These principles in hand, we can turn back to doctrine and begin to see why courts and litigants sometimes get lost. First Amendment law includes lines of cases about government directly regulating or limiting expression, cases about government selectively subsidizing expression, and cases about government leveraging a subsidy to control expression beyond the subsidy program. When it comes to direct regulation—municipal restrictions on outdoor signs, for example—the government generally can’t discriminate based on content.

Within each doctrinal category, these tests seem clear enough. The trick is knowing which category applies: whether a funding program operates more like a selective subsidy or a targeted restriction,

The real work here comes not in labeling something a “subsidy,” but in determining the bounds and the point of a subsidy program and deciding whether it’s big enough to distort, crowd out, or target other, non-subsidized expression. To do that work in regard to the PPP, courts need to ask whether the program is so sweeping and important, and the SBA’s exclusions are so targeted, viewpoint-laden, or removed from the point of the program that they should be treated as an abridgment of expression, not just an ordinary governmental choice about where to allocate scarce resources.

III. Why Strip Clubs Should Win and Lobbyists Lose

When the issue is framed like this, the adult businesses challenging their exclusion from the PPP appear to have a far more compelling claim than do most businesses who have lost out on government funding, political lobbyists included.

To start: the PPP is a different kind of government subsidy than most others. It differs in its staggering size—$659 billion in forgivable loans—and, even more importantly, in its scope: as Part I explained, “any business concern, nonprofit organization, veterans organization, or Tribal business concern” with 500 or fewer employees is eligible, and larger entities in particular industries (especially hotels and restaurants) qualify too.

The context in which the PPP was passed matters too, for the largest economic relief package in American history was meant to address what is clearly seen as an existential threat to small businesses, if not the entire economy. Throwing someone a life preserver and building them a bigger yacht may both be subsidies, but a refusal to offer the former is felt rather differently than the latter. When subsidies are a lifeline, their denial operates more like a bar: that which goes unsubsidized will likely cease to exist. The claim is not that all businesses will fold unless they are given PPP loans. The point is just that the more recipients’ survival depends on a subsidy, the less the subsidy/abridgement dichotomy does any work in the speech context. The traditional argument that those denied government subsidies for their speech can simply continue speaking on their own dime loses force when fewer dimes are out in private circulation.

These facts about the unusual size, scope, and importance of the PPP apply to the strip club and political lobbying cases in equal measure. Compared to businesses on the losing end of ordinary pork barrel politics, anyone excluded from the PPP has much stronger cause for complaint. The sweep of the PPP is just far broader than an ordinary earmarked subsidy, a bailout of a particular industry, a focused tax benefit (like the mortgage interest deduction for homeowners), or even the tax exempt status more broadly given to non-profit organizations under § 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code.

This last point is especially important in the lobbying case. There, the government bases much of its argument on Regan v. Taxation with Representation, a 1983 case in which the Supreme Court found no First Amendment problem in denying lobbying organizations § 501(c)(3) status. Regan is obviously highly relevant, not least for what it has to say about the government’s interest in treating lobbyists differently than others. Even so, the subsidy offered in the tax code is importantly different than that in the PPP. The subset of non-profit organizations that benefit under § 501(c)(3)—those dedicated to religious, charitable, educational and other specified purposes

Though the PPP’s breadth and importance are points in favor of both the adult businesses’ and the lobbyists’ claims, the nature of their respective exclusions from the PPP differs. And this difference proves determinative. The SBA’s exclusions of prurient businesses and lobbyists can be distinguished in two important ways.

First, the government has actually offered reasons for its bar on lobbyists—unlike the prurient business bar. The SBA points to a longstanding, “[g]overnment-wide Federal policy that Federal funds not be used for lobbying or political activities because to do so would not be an appropriate or cost-effective use of Federal tax dollars.”

By contrast, the government’s justifications for the prurient business bar amount to nothing more than: it’s been around a long time, and it serves the public interest.

This distinguishes the prurient business bar from the bar against lobbyists, which reflects a broader effort to avoid even the appearance of partisan favoritism in government funding. For that matter, it distinguishes the prurient business bar from most of the SBA’s other exclusions too, like that barring companies that have defaulted on federal loans (a financial safeguard), the bar on foreign businesses (advancing the SBA’s goal of fostering small American businesses), the bar on discriminatory clubs (meant to avoid government participation in such discrimination), or the bar on businesses devoted to religious indoctrination (which, at least in former times,

Singling out particular forms of expression within an otherwise broadly available funding program requires, at minimum, a justification reasonably related to the aims of the program. And there is no evidence that promoting expression that is “wholesome” rather than prurient is in any way related to the goals of the CARES Act, or even the Small Business Act. (That means exclusions to the SBA’s pre-existing loan programs for small businesses—though never before challenged—likely share the same constitutional vulnerabilities now being exposed in the higher-stakes context of the PPP.)

One thing clearly prohibited—even according to the subsidies cases on which the government most strongly relies—is a doling out of “subsidies in such a way as to aim at the suppression of dangerous ideas.”

To be sure, a plurality of Justices on the Supreme Court has sometimes denied that regulations of adult businesses discriminate of the basis of viewpoint. In 1976, Justice Stevens wrote for four Justices in Young v. American Mini Theatres that a restriction on sexually explicit films applies no matter the “social, political, or philosophical message a film may be intended to communicate.”

In fact, the only ground on which a majority of the Court has ever agreed to uphold restrictions like these is the so-called secondary effects doctrine, which permits the government to regulate adult businesses when its goal is to prevent crime or economic harm in the surrounding area, rather than to suppress expression.

The two differences between the lobbying and prurience bars—their justification and their viewpoint neutrality—matter in at least three doctrinal ways.

First, if the prurient business bar discriminates against a viewpoint, then the freedom-to-subsidize cases on which the government primarily relies no longer apply to it. Regan, which permitted the exclusion of lobbying organizations from 501(c)(3)’s tax exemptions, was explicit: “The case would be different if Congress were to discriminate invidiously in its subsidies in such a way as to aim at the suppression of dangerous ideas.”

Second, insofar as the PPP is treated as a limited public forum, the government may reserve its funding for certain speakers or topics, but limits must be reasonable in light of the legitimate purposes for which the forum was established. Within the forum’s bounds, viewpoint discrimination is not allowed.

Both the justification and viewpoint distinctions might apply if a court treats the PPP as a limited public forum. If the PPP is characterized as a forum (i.e., fund) for small domestic businesses, then it shouldn’t matter what views any particular small domestic business has about sex. Distinguishing among small businesses in this way is viewpoint discriminatory. Lobbyists aren’t similarly judged based on their views. By contrast, if the various business exclusions are seen as setting the boundaries of this limited public forum, then the government needs to show that excluding each class of speakers is reasonable in light of the forum’s purpose. This would be akin to limiting a quad to current students or a bulletin board to departmental announcements, both of which are allowable. As noted above, the exclusion of lobbyists can be explained by a desire to avoid the appearance of corruption or partisan entanglement, which would undermine confidence in federal funding programs like the PPP. Excluding prurient businesses can only be explained by distaste for what they express—an aim that’s irrelevant to the PPP’s goal of helping small businesses pay their workers during the current economic crisis.

Third, a similar analysis applies to an unconstitutional conditions claim. The Supreme Court has sought to distinguish “between conditions that define the limits of the government spending program—those that specify the activities Congress wants to subsidize—and conditions that seek to leverage funding to regulate speech outside the contours of the program itself.”

IV. Courts Are Expressive Subsidies Too

The PPP cases are playing out within a court system which is itself a multi-billion-dollar governmental subsidy for expression. And ironically, at least some of the plaintiffs in these cases aren’t just going to court to complain about expressive subsidies they’ve been denied; they are also trying to cut off support courts would standardly provide for the expressive activities of plaintiffs’ opponents.

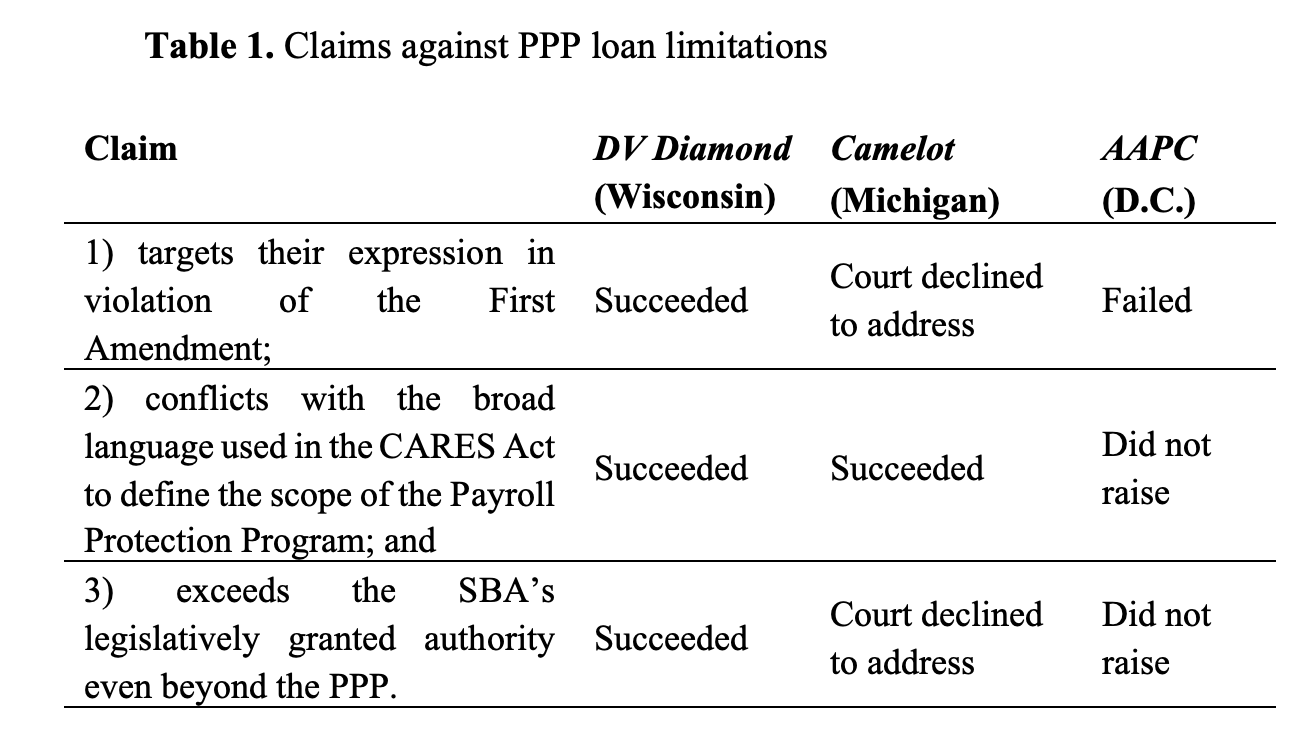

Before explaining this irony further, a concluding recap and scorecard of plaintiffs’ own claims might be in order. With $659 billion up for grabs, adult entertainment businesses have successfully argued in Wisconsin that the SBA’s bar on loans to prurient businesses likely

1) targets their expression in violation of the First Amendment;

2) conflicts with the broad language used in the CARES Act to define the scope of the Payroll Protection Program; and

3) exceeds the SBA’s legislatively granted authority even beyond the PPP.

(If we’re keeping score, I think the district court was right on (1) and probably (2) but not (3).

Meanwhile, in the District of Columbia, political lobbyists raised a First Amendment claim akin to (1), which both the district and circuit courts deemed unlikely to succeed. Lobbyists did not bring the statutory claims, (2) and (3), that have proven successful in the Midwest, though less so elsewhere.

Table 1. Claims against PPP loan limitations

Lobbyists certainly trade in expression closer to the core of the First Amendment than the nude dancing subject to the prurient business bar. But that is not what ultimately distinguishes these cases. Doctrinal niceties aside, what matters is not that lobbyists’ speech is more politically important, but that strip clubs’ expression is less politically popular. When it comes to prurient businesses as compared to lobbyists, the problem with the PPP is that it picks out, and picks on, strip clubs’ expression for no reason other than its unpopularity.

So unpopular is the strip clubs’ expression, in fact, that several items on the docket in the Michigan case have been filed under seal for protective reasons. This is the kind of mundane procedure detail that generally goes unnoticed. But here it sheds light not only on the free speech interests of the plaintiffs, but also of their opponents. Both, it turns out, are reliant on governmental subsidies for their expression.

According to the motion to seal in the Michigan case, disclosing the names of lenders willing to work with strip clubs might “open up those non-parties to harassment aimed at suppressing Plaintiffs’ expressive activities.”

The government did not oppose the motions to seal, and the district court allowed the redactions through text orders, with no discussion of how plaintiffs had “overcome the strong public interest in favor of access to court records.”

The Sixth Circuit has said that the public’s “First Amendment and common law right of access to court filings” gets harder to overcome “the greater the public interest in the litigation’s subject matter.”

Lest the irony here be missed: the strip clubs are trying to cut off a state subsidy because it enables expression they don’t like. Courts are a public good not least because of the way they subsidize and facilitate the investigation and disclosure of information in the course of taxpayer-funded adjudication.

The motions to seal thus reenact the fight over exclusion from the PPP in miniature, and with the strip clubs’ interests reversed. And in both, the proper response is the same. The state needs to come forward with a better reason than it has so far offered if it is going to deny a broad benefit to some simply because of worries about how they will use it.

Copyright © 2020 Brian Soucek, Professor of Law and Martin Luther King, Jr. Hall Research Scholar, University of California, Davis School of Law. Thanks to Ash Bhagwat, Jessica Clarke, and Chris Odinet for hugely clarifying conversations and sometimes disagreements about these issues. Thanks also to Jack Mensik for his research assistance, and to Dean Kevin Johnson and the UC Davis School of Law for funding it. DOI: https://doi.org/10.15779/Z38BG2HB1P.

- Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act), Pub. L. No. 116-136, 134 Stat. 281 (2020). ↑

- Barnes v. Glen Theater, Inc., 501 U.S. 560, 566 (1991) (plurality opinion). ↑

- DV Diamond Club of Flint, L.L.C. v. SBA, No. 20-cv-10899, 2020 WL 2315880 (E.D. Mich. May 11, 2020) (order granting preliminary injunction). ↑

- Camelot Banquet Rooms, Inc. v. SBA, No. 20-C-0601, No. 20-C-634, 2020 WL 2088637 (E.D. Wis. May 1, 2020) (order granting preliminary injunction). ↑

- DV Diamond Club of Flint, L.L.C. v. SBA, No. 20-1437 (6th Cir. May 15, 2020) (order denying motion for stay pending appeal); Motion of Respondent-Appellant for Stay Pending Appeal and Immediate Administrative Stay, Camelot Banquet Rooms, Inc. v. SBA, No. 20-1729, No. 20-1730 (7th Cir. May 4, 2020). ↑

- Am. Ass’n of Political Consultants v. SBA, No. 20-5101 (D.C. Cir. May 26, 2020) (order affirming the district court); Am. Ass’n of Political Consultants v. SBA, No. 20-970 (D.D.C. Apr. 21, 2020) (order denying preliminary injunction). On June 17, the parties filed a stipulated dismissal without prejudice in the district court. See Notice of Voluntary Dismissal, Am. Ass’n of Political Consultants v. SBA, No. 20-970 (D.D.C. June 17, 2020). ↑

- Matal v. Tam, 137 S. Ct. 1744, 1760 (2017). ↑

- CARES Act, Pub. L. No. 116-136, 134 Stat. 281 (2020); Heather Caygle & Sarah Ferris, House Passes $484 billion Relief Package After Weeks of Partisan Battles, Politico (Apr. 23, 2020, 7:23 PM EDT), https://www.politico.com/news/2020/04/23/house-vote-pass-coronavirus-aid-package-203965 [https://perma.cc/J4RH-F524] (package included $321 billion infusion for the Paycheck Protection Program following the program’s initial depletion); Li Zhou, The Paycheck Protection Program Has Already Run Out of Money, Vox (Apr. 16, 2020, 2:20 PM EDT), https://www.vox.com/2020/4/16/21223637/paycheck-protection-program-funding [https://perma.cc/Q8MP-YTF2] (initial $349 million in PPP funds passed in late March 2020 were depleted by April 16, 2020). ↑

- Jessica Silver-Greenberg, et. al., Large, Troubled Companies Got Bailout Money in Small-Business Loan Program, N.Y. Times (Apr. 26, 2020, updated May 13, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/26/business/coronavirus-small-business-loans-large-companies.html [https://perma.cc/3SWQ-UKYW] (more than 200 publicly traded companies have disclosed receiving a total of more than $750 million in bailout loans); Alicia Wallace, Shake Shack, Ruth’s Chris and Other Chain Restaurants Got Big PPP Loans when Small Businesses Couldn’t, CNN Business (Apr. 20, 2020, 12:27 PM EDT), https://www.cnn.com/2020/04/19/business/small-businesses-ppp-loans-chain-restaurants/index.html [https://perma.cc/X8HG-2C87]; Li Zhou, Why Major Food and Hotel Chains Are Getting Stimulus Money Meant for Small Businesses, Vox (Apr. 22, 2020, 4:40 PM EDT), https://www.vox.com/2020/4/22/21229319/ruth-chris-shake-shack-potbelly-ppp-loans [https://perma.cc/2TRX-5P9T] (9 percent of PPP loans went to 0.3 percent of businesses that applied). ↑

- Flandreau Santee Sioux Tribe v. Carranza, No. 4:20-cv-04070 (D.S.D. Apr 23, 2020). ↑

- Payday Loan, L.L.C. v. SBA, No. 1:20-cv-1084 (D.D.C. Apr. 25, 2020). ↑

- Nat’l Ass’n of Home Builders v. SBA, No. 20-cv-11780-DML-RSW (E.D. Mich. June 30, 2020). ↑

- Complaint at 3 n.5, Alpha Visions Learning Academy, Inc. v. Carranza, No. 2:20-ap-00071 (Bankr. W.D. Tenn. May 14, 2020) (citing eight other bankruptcy court proceedings involving the PPP). ↑

- MoveCorp v. SBA, No. 20-cv-1739 (D.D.C. June 25, 2020); Defy Ventures, Inc. v. SBA, No. 20-cv-1838-CCB (D. Md. June 16, 2020); Carmen’s Corner Store v. SBA, No. 20-cv-1736-GLR (D. Md. June 10, 2020). ↑

- 85 Fed. Reg. 20811 (Apr. 15, 2020). ↑

- See infra notes 29-37 and accompanying text (discussing APA challenges to the SBA’s rulemaking). ↑

- See 13 C.F.R. § 120.110. ↑

- See id.; see also U.S. Small Bus. Admin., Office of Fin. Assistance, Standard Operating Procedure 50 10 5(K), Subpart B, Chapter 2 (2019). ↑

- Id. ↑

- Am. Ass’n. of Political Consultants v. SBA, No. 20-970 (D.D.C. Apr. 21 2020). ↑

- For example, during the previous economic crisis, the SBA-guaranteed loan program authorized under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 amounted to just $255 million. See U.S. Gov’t Accountability Off., GAO-10-298R, Status of the Small Business Administration’s Implementation of Administrative Provisions in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 8 (2010). Before supplemental funds were authorized after the outbreak of the pandemic, the SBA began the fiscal year with less than $1.2 billion available to it. See Robert Jay Dilger, Cong. Research Serv., R43846, Small Business Administration (SBA) Funding: Overview and Recent Trends 4 tbl.1 (2020). ↑

- Miller v. California, 413 U.S. 15 (1973). ↑

- Business Loan Programs, 60 Fed. Reg. 64,356, 64,360 (Dec. 15, 1995). The SBA’s mandate to consider the “public interest,” now found at 15 U.S.C. § 633(d), descended from “identical” language governing the SBA’s predecessor, the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC). See S. Comm. on Banking and Finance, Establishment of Small Business Administration and Liquidation of Reconstruction Finance Corporation, S. Rep. No. 604, at 6 (1953). A product of the Great Depression, the RFC dispensed low-interest government loans, and came under Congressional scrutiny in the early 1950s due to allegations of undue political influence over its lending policy by the Truman administration. See generally David McCullough, Truman 863-870 (1992). Before dismantling the RFC and establishing the SBA in 1953, lawmakers in 1951 reorganized RFC leadership, creating a Loan Policy Board to “establish general policies (particularly with reference to the public interest involved in the granting and denial of applications . . . .)” 5 U.S.C. app. 1, Reorganization Plan No. 1 of 1951, sec. 6; see also U.S. Dep’t of the Treasury, Final Report on the Reconstruction Finance Corporation: Pursuant to Section 6(c), Reorganization Plan No. 1 of 1957, at 25 (1959). More explicit policies were needed, for as one RFC Director testified at the time, “We were given a job to make loans to small businesses and we were also given a job to make loans in those cases where there was a public interest. Now, where can you draw the line, Senator, I don’t know, and I would like to know.” Hearings Before a Subcomm. of the S. Comm. on Banking and Currency: A Study of the Operations of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation Pursuant to S. Res. 219: Lending Policy, 81st Cong. 151 (1951) (testimony of William E. Willett, Member, Board of Directors, Reconstruction Finance Corporation). But see id. at 150-51 (agreeing that loans to night clubs would not be in the public interest). ↑

- Business Loan Programs, 60 Fed. Reg. at 64,360. ↑

- Complaint, DV Diamond Club of Flint, L.L.C. v. SBA, No. 20-cv-10899 (E.D. Mich. May 11, 2020). DV Diamond also alleged a due process violation, but as a claim that the SBA is irrationally distinguishing among various entertainment enterprises, this adds little to the claims under the First Amendment. ↑

- Complaint, Camelot Banquet Rooms, Inc. v. SBA, No. 20-C-0601 (E.D. Wis. May 1, 2020). ↑

- Id. Additional claims have followed since the initial decisions in DV Diamond and Camelot Banquet Rooms. See, e.g., D. Houston, Inc. v. SBA, No. 20-cv-2308 (S.D. Tex. June 30, 2020) (alleging only constitutional claims); Admiral Theatre, Inc. v. SBA, No. 20-CV-2807 (N.D. Ill. May 15, 2020) (alleging constitutional and administrative law claims); McCarthy v. Cuomo, No. 2:20-cv-02124 (E.D.N.Y. May 9, 2020) (bringing a Due Process Clause claim against the Small Business Administration amidst a broader set of claims against the Governor of New York for his closure of non-essential businesses). A more recent complaint in the Northern District of California raises a similar combination of claims but against 13 C.F.R. § 120.201, the regulations SBA has applied to the $10 billion Emergency Economic Injury Disaster Loan program, 15 U.S.C. § 9009(e). See Deja Vu—San Francisco, LLC v. SBA, No. 20-cv-3982 (N.D. Cal. June 15, 2020). ↑

- Complaint, Am. Ass’n. of Political Consultants v. SBA, No. 20-970 (D.D.C. Apr. 21, 2020). ↑

- Id. ¶ 47 (citing CARES Act §1102(a)(1)(B)(2)(D)(i) (2020) (emphasis added)). ↑

- In fact, the SBA has not imposed all of 120.110’s eligibility limits. The regulation’s bar on non-profits is made inapplicable by the CARES Act’s explicit inclusion of 501(c)(3) organizations, see 15 U.S.C. §§ 636(a)(36)(A)(vii); 636(a)(36)(D)(i). Similarly, for faith-based organizations, the SBA has lifted its general policy of considering affiliates when determining a borrower’s size, see 13 C.F.R. § 121.301, having decided that this expansion of eligibility for the PPP is “required, or at a minimum authorized, by the Religious Freedom Restoration Act [42 U.S.C. § 2000bb–1].” See 85 Fed. Reg. 20817, 20819 (Apr. 15, 2020). But see Texas Monthly, Inc. v. Bullock, 489 U.S. 1 (1989) (striking down a state tax exemption offered only to religious publications under the Establishment Clause); Micah Schwartzman, Richard Schragger & Nelson Tebbe, The Separation of Church and State is Breaking Down Under Trump, The Atlantic (June 29, 2020), https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/06/breakdown-church-and-state/613498/ [https://perma.cc/6DV9-24S4]. ↑

- See supra note 3. ↑

- DV Diamond Club of Flint, L.L.C. v. SBA, No. 20-cv-10899, 2020 WL 2315880 at *10 (E.D. Mich. May 11, 2020) (order granting preliminary injunction). ↑

- CARES Act § 1102(a) (emphases added). The CARES Act defines “small business concerns” in reference to 15 U.S.C. § 636, the section to which the SBA’s traditional exclusions of 13 C.F.R. § 120.110 apply. See CARES Act § 1101. ↑

- DV Diamond Club of Flint, 2020 WL 2315880 at *14. ↑

- Camelot Banquet Rooms, Inc. v. SBA, No. 20-C-0601, No. 20-C-634, 2020 WL 2088637 at 7 (E.D. Wis. May 1, 2020) (order granting preliminary injunction). The Wisconsin court’s administrative law holding goes further than the court in Michigan—too far. Like the court in Michigan, it holds that the CARES Act prohibits the SBA from applying its traditional exclusions to the PPP. But it also holds that the SBA’s traditional exclusions themselves go beyond the SBA’s statutory authority. This seems wrong. The Wisconsin court rests its claim on 15 U.S.C. § 636(a), which “empower[s]” the SBA to “to make loans to any qualified small business concern” and then limits the shape those loans must take. Camelot Banquet Rooms, 2020 WL 2088637 at 7. But empowering the SBA’s loanmaking is a far different thing than requiring it. And the court is focused on the wrong section of the U.S. Code. Whereas § 636 places statutory limits on SBA loans, previous sections describe what “small business concerns” are eligible to get those loans. In particular, § 632(a) dictates how “small” should be determined and § 633(d) instructs the SBA to set policies “which shall govern the granting and denial of applications for financial assistance”—and to do so “particularly with reference to the public interest involved.” See 15 U.S.C. §§ 632(a), 633(d). This is the authority on which the SBA relied in establishing the prurient business bar in 1995. See supra note 23. ↑

- See Memorandum, Defy Ventures, Inc. v. SBA, No. 20-cv-1738 (D. Md. June 29, 2020) (finding that Congress has not clearly spoken as to whether the SBA may impose additional eligibility restrictions on PPP participants); Decision and Order, Diocese of Rochester v. SBA, No. 20-cv-6243 (W.D.N.Y. June 10, 2020) (holding that the SBA did not exceed its statutory authority under the CARES Act when it excluded debtors in bankruptcy from participation in the PPP). ↑

- See Defy Ventures at 15 *(referring to the CARES Act’s inclusion of sole proprietors and independent contractors, those who may be able to get credit elsewhere, and those who lack the collateral ordinarily required by the SBA). ↑

- In what follows, I treat claims under the Fifth Amendment also as “speech claims,” since they allege one of two speech-related things: (a) businesses are being treated differently due to the content of their speech, in violation of the equal protection component of the Due Process Clause; or (b) excluding businesses from the PPP because of their speech is illegitimate, arbitrary, or irrational—thus a violation of due process. ↑

- See supra note 6. ↑

- See Complaint at 3, Am. Ass’n. of Political Consultants v. SBA, No. 20-970 (D.D.C. Apr. 21, 2020). To be clear, the AAPC couldn’t have brought a statutory claim on its own behalf, as it is a 501(c)(6) organization and the inclusion of “nonprofit organizations” in the PPP is limited to 501(c)(3)s. But the AAPC’s complaint was made on behalf of its members, many of whom would qualify as eligible “business concerns” were the traditional exclusions found inapplicable. And its co-plaintiff, the Colorado consulting firm RidderBraden, could surely have made the argument directly. ↑

- See, e.g., Am. Ass’n of Political Consultants v. SBA, No. 20-970, 2020 WL 1935525 (D.D.C. Apr. 21, 2020) (order denying preliminary injunction). Because the case was at the preliminary injunction stage, the district court did not dismiss AAPC’s claims but found them unlikely to succeed on the merits. ↑

- Camelot Banquet Rooms, 2020 WL 2088637 at *11. ↑

- NEA v. Finley, 524 U.S. 569 (1998). ↑

- Ysursa v. Pocatello Educ. Ass’n, 129 S. Ct. 1093 (2009); Rust v. Sullivan, 500 U.S. 173 (1991); Agency for Int’l Dev. v. All. for Open Soc’y Int’l, Inc., 133 S. Ct. 2321 (2013). See also Matal v. Tam, 137 S. Ct. 1744, 1761-62 (2017). ↑

- Ark. Writers’ Project, Inc. v. Ragland, 481 U.S. 221 (1987); Minneapolis Star Tribune Co. v. Minn. Comm’r of Revenue, 460 U.S. 575 (1983); Regan v. Taxation with Representation of Wash., 461 U.S. 540 (1983). ↑

- Rosenberger v. Rector & Visitors of the Univ. of Va., 515 U.S. 819 (1995); Legal Serv. Corp. v. Velazquez, 531 U.S. 533 (2001). ↑

- Elrod v. Burns, 427 U.S. 347 (1976); Rumsfeld v. Forum for Acad. & Inst. Rights, Inc., 547 U.S. 47 (2006); Speiser v. Randall 357 U.S. 513 (1958). ↑

- Compare Rosenberger, 515 U.S. at 831-32 (acknowledging that the distinction “is not a precise one,” but finding viewpoint discrimination), with Rosenberger, 515 U.S. at 893-97 (Souter, J., dissenting) (finding no viewpoint discrimination in denying funding to organizations that promote views on religion). ↑

- Cf. Iancu v. Brunetti, 139 S. Ct. 2294, 2298-99 (2019) (describing the Court’s inability to “agree on the overall framework for deciding” how to treat federal trademark registration under the First Amendment). ↑

- In response to the Eastern District of Michigan’s local rules, which require briefs to identify the “most appropriate authority” in the case, see E.D. Mich. LR 7.1(d)(2), plaintiffs in DV Diamond focus on content discrimination and obscenity cases, while the government lists cases about awards, tax exemptions, and targeted funding programs. ↑

- See Dan Charles, Farmers Got Billions from Taxpayers in 2019, and Hardly Anyone Objected, NPR (Dec. 31, 2019, 4:13 PM), https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2019/12/31/790261705/farmers-got-billions-from-taxpayers-in-2019-and-hardly-anyone-objected [https://perma.cc/6WSD-AD5L]; Dylan Matthews, Trump’s New Bailout Program for Farmers and Ranchers, Explained, Vox (Apr. 18, 2020, 12:20 PM), https://www.vox.com/2020/4/18/21226253/trump-farm-bailout-food-stamps-snap [https://perma.cc/QCE6-44GJ]. ↑

- See Winners and Losers in Congress’s $2 Trillion Virus Rescue Plan, Bloomberg (March 22, 2020 5:23 PDT, updated March 25 2020, 10:42 PM PDT), https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-03-23/gop-s-2-trillion-bill-adds-cash-for-bailouts-states-transit [https://perma.cc/ZQ52-7QDV]; David Welch, Hertz, Avis Ask to Be Included in Rescue of Travel Industry, Bloomberg (March 19, 2020 4:17 PM PDT, updated March 20, 2020 7:02 AM PDT), https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-03-19/hertz-avis-ask-to-be-included-in-u-s-rescue-of-travel-industry [https://perma.cc/MC65-S3NP]; Peter Whoriskey & Heather Long, Retailers Employ Millions. But the Government’s Rescue Could Leave Out Some of the Biggest Names, Wash. Post (Apr. 7, 2020 9:15 AM PDT), https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/04/07/bailout-retail-cares-act/ [https://perma.cc/Z5BE-3KHA]. ↑

- The most famous and sweeping example comes from another time of massive economic disruption: the Works Progress Administration, formed during the Depression. For an overview, see Jennifer C. Lena, Entitled: Discriminating Tastes and the Expansion of the Arts ch. 2 (2019). For a wide-ranging description of current-day government-funded artmaking and architecture in the federal courts, see generally Judith Resnik & Dennis E. Curtis, Representing Justice: Invention, Controversy, and Rights in City-States and Democratic Courtrooms (2011). For an interesting history of governmental graphic design, see Diana Budds, Nixon, NASA, and How the Federal Government Got Design, FAST CO.DESIGN (Mar. 6, 2017, 7:00 AM), https://www.fastcodesign.com/3068659/nixon-nasa-and-how-the-federal-government-got-design [https://perma.cc/4LHV-FMEV]. ↑

- NEA v. Finley, 524 U.S. 569 (1998). ↑

- See Brian Soucek, Aesthetic Judgment in Law, 69 Ala. L. Rev. 381, 387-89, 404-12 (2017). ↑

- Leathers v. Medlock, 499 U.S. 439 (1991). ↑

- See Soucek, supra note 55, at 459-64. ↑

- See Regan v. Taxation with Representation of Wash., 461 U.S. 540, 549-50 (1983). ↑

- See Seth F. Kreimer, Allocational Sanctions: The Problem of Negative Rights in a Positive State, 132 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1293, 1374 (1984). ↑

- See Grosjean v. Am. Press Co., 297 U.S. 233 (1936). ↑

- Postage Rates for Periodicals: A Narrative History, U.S. Postal Serv. (June 2010), https://about.usps.com/who-we-are/postal-history/periodicals-postage-history.htm. ↑

- See Robert C. Post, Subsidized Speech, 106 Yale L.J. 151, 157-58, 182 (1996). ↑

- U.S. Const. amend. I (“Congress shall make no law . . . abridging the freedom of speech . . . .”). ↑

- National Endowment for the Arts Appropriations History, https://www.arts.gov/open-government/national-endowment-arts-appropriations-history [https://perma.cc/GM27-EYMB]. ↑

- See, e.g., Minneapolis Star Tribune Co. v. Minn. Comm’r of Revenue, 460 U.S. 575 (1983) (observing that when the state “selects such a narrowly defined group to bear the full burden of the tax, the tax begins to resemble more a penalty for a few of the largest newspapers than an attempt to favor struggling smaller enterprises”); see also Laura V. Farthing, Note, Arkansas Writers’ Project v. Ragland: The Limits of Content Discrimination Analysis, 78 Geo. L. Rev. 1962, 1969 (1990); Kreimer, supra note 59 at 1352, 1367. ↑

- See Reed v. Town of Gilbert, 135 S. Ct. 2218 (2015). ↑

- See, e.g., Rosenberger v. Rector & Visitors of the Univ. of Va., 515 U.S. 819 (1995). ↑

- See, e.g., Agency for Int’l Dev. v. All. for Open Soc’y Int’l, Inc., 133 S. Ct. 2321 (2013). Similar principles apply in cases involving speech by government employees. See, e.g., Garcetti v. Ceballos, 547 U.S. 410 (2006); Pickering v. Bd. of Educ., 391 U.S. 563 (1968). ↑

- Compare Ark. Writers’ Project, Inc. v. Ragland, 481 U.S. 221 (1987) (striking down a tax scheme as a content-discriminatory burden), with id. at 235 (Scalia, J., dissenting) (treating the scheme’s exemptions as a subsidy). ↑

- See sources cited in note 9, supra. ↑

- See 26 U.S.C. § 501(c)(3); see also Regan, 461 U.S. at 544 (“Both tax exemptions and tax deductibility are a form of subsidy that is administered through the tax system.”). ↑

- 26 U.S.C. § 501(c)(3) (extending tax exemptions to entities “organized and operated exclusively for religious, charitable, scientific, testing for public safety, literary, or educational purposes, or to foster national or international sports competition . . . or for the prevention of cruelty to children or animals”). ↑

- Brief of Petitioner-Appellant at 4, Am. Ass’n of Political Consultants v. SBA, No. 20-5101 (D.C. Cir. May 26, 2020) (citing 51 Fed. Reg. 37,580, 37,589 (Oct. 23, 1986)). ↑

- See, e.g., 18 U.S.C. § 1913; 31 U.S.C. § 1352; see also Office of Mgmt. & Budget, Exec. Office of the President, OMB Circular A-122, Cost Principles for Non-Profit Organizations (2004); Cong. Research Serv., RL34725, “Political” Activities of Private Recipients of Federal Grants or Contracts (2010). ↑

- Brief of Petitioner-Appellant at 13-14, Am. Ass’n of Political Consultants v. SBA, No. 20-5101 (D.C. Cir. May 26, 2020); Ysursa v. Pocatello Educ. Ass’n, 129 S. Ct. 1093 (2009). ↑

- Motion of Respondent-Appellant for Stay Pending Appeal and Immediate Administrative Stay at 4, 10, Camelot Banquet Rooms, Inc. v. SBA, No. 20-1729, No. 20-1730 (7th Cir. May 4, 2020). ↑

- Business Loan Programs, 60 Fed. Reg. 64356, 64360 (Dec. 15, 1995). For more on the public interest justification, see supra note 23. ↑

- Compare id. at 64360 (citing Establishment Clause cases from Everson v. Bd. of Educ., 330 U.S. 1 (1947), to Bowen v. Kendrick, 487 U.S. 589 (1988), to justify the SBA’s restriction), with Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia, Inc. v. Comer, 137 S. Ct. 2012 (2017) (holding that the Free Exercise Clause prevents the state from “disqualifying [otherwise eligible recipients] from a public benefit solely because of their religious character”). ↑

- Regan v. Taxation with Representation of Wash., 461 U.S. 540, 548 (1983) (quotation marks and alterations omitted); see also Ysursa, 129 S. Ct. at 1098. ↑

- 13 C.F.R. § 120.110(p)(2) (2020). ↑

- Young v. Am. Mini Theatres, Inc. 427 U.S. 50, 70 (1976). ↑

- Geoffrey R. Stone, Restrictions of Speech Because of Its Content: The Peculiar Case of Subject-Matter Restrictions, 46 U. Chi. L. Rev. 81, 112 (1978). ↑

- See Renton v. Playtime Theatres, Inc., 475 U.S. 41 (1986); Smolla & Nimmer on Freedom of Speech §§ 9:18-21 (2020). ↑

- City of Erie v. Pap’s A. M., 529 U.S. 277, 313 (2000) (Souter, J., concurring in part and dissenting in part). I characterize the evidentiary requirement as “arguable” because it comes from Justice Souter, who made it the price of a fifth vote for relying on the secondary effects doctrine in Pap’s A. M. Only three Justices from the Pap’s A. M. Court remain on the Court today. ↑

- 60 Fed Reg 64356, 64360 (Dec. 15, 1995) (citing obscenity and funding decisions but not Barnes v. Glen Theatre, Renton v. Playtime Theatres, or any other secondary effects cases). ↑

- See Regan v. Taxation with Representation of Wash., 461 U.S. 540, 548 (1983). ↑

- Rosenberger v. Rector & Visitors of the Univ. of Va., 515 U.S. 819, 829-30 (1995). ↑

- Agency for Int’l Dev. v. All. for Open Soc’y Int’l, Inc., 133 S. Ct. 2321, 2328 (2013); see generally Kathleen M. Sullivan, Unconstitutional Conditions, 102 Harv. L. Rev. 1413 (1989). ↑

- See supra note 35. ↑

- See supra notes 36-37 and accompanying text. ↑

- Brief of Petitioner in Support of Motion to File Documents Under Seal at 7, DV Diamond Club of Flint, L.L.C. v. SBA, No. 20-cv-10899 (E.D. Mich. May 11, 2020). ↑

- Id. at 3. ↑

- Id. at 7. Plaintiffs do mention Operation Choke Point, id., a now-ended federal initiative that scrutinized and pressured banks working with disfavored businesses like strip clubs. See Joe Mont, Operation Choke Point Finally Suffocated by Justice Department, Compliance Week (Aug. 29, 2017), https://www.complianceweek.com/operation-choke-point-finally-suffocated-by-justice-department/2541.article [https://perma.cc/NHE6-KE46]. ↑

- Rudd Equip. Co. v. John Deere Constr. & Forestry Co., 834 F.3d 589, 596 (6th Cir. 2016). ↑

- See Shane Grp., Inc. v. Blue Cross Blue Shield of Mich., 825 F.3d 299, 306 (6th Cir. 2016) (“[A] district court that chooses to seal court records must set forth specific findings and conclusions which justify nondisclosure to the public. That is true even if neither party objects to the motion to seal. . . . And a court’s failure to set forth those reasons—as to why the interests in support of nondisclosure are compelling, why the interests supporting access are less so, and why the seal itself is no broader than necessary—is itself grounds to vacate an order to seal.”). ↑

- Rudd, 834 F.3d at 595, 594 (quotation marks and citations omitted). Unlike the Sixth Circuit, the Supreme Court has not explicitly rooted the right of public access to civil court filings in the First Amendment, as opposed to federal common law. For more on why it should, see David S. Ardia, Court Transparency and the First Amendment, 38 Cardozo L. Rev. 835 (2017). ↑

- See generally John Cassidy, Who Should Get Bailed Out in the Coronavirus Economy?, New Yorker (Apr. 23, 2020), https://www.newyorker.com/news/our-columnists/who-should-get-bailed-out-in-the-coronavirus-economy [https://perma.cc/C4HF-PCQX]; Tim Wu, Opinion, The Small-Business Aid Program Has Been a Fiasco, N.Y. Times (Apr. 21, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/21/opinion/paycheck-protection-program.html [https://perma.cc/6265-GXNE]; Li Zhou, Many Small Businesses Are Being Shut Out of a New Loan Program by Major Banks, Vox (Apr. 7, 2020 3:40 PM EDT), https://www.vox.com/2020/4/7/21209584/paycheck-protection-program-banks-access [https://perma.cc/7MW8-TFHX]. ↑

- Readers struggling to sympathize with those who’d want to pressure banks to stop working with strip clubs might instead imagine PPP-funded loans going to discriminatory membership clubs or other businesses, were that regulation lifted. See 13 C.F.R. § 120.110(i) (2020). ↑

- See Judith Resnik, The Contingency of Openness in Courts: Changing the Experiences and Logics of the Public’s Role in Court-Based ADR, 15 Nev. L.J. 1631, 1648-49 (2015) (describing how the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure opened up “opportunities to obtain documents from opponents (including governments and commercial enterprises)” which, since presumptively public, “turned discovery into . . . the ‘poor person’s FBI.’” (quoting Owen Fiss)). ↑