#BlackLivesMatter—Getting from Contemporary Social Movements to Structural Change

This piece is part of the Reckoning and Reformation Symposium, which brings together scholars writing broadly about the law, justice, race, and inequality. California Law Review published two other pieces as part of this joint effort with other law reviews:

Introduction

From the haters and hackers to propaganda and privacy concerns, social media often deserves its bad reputation. But the sustained activism that followed George Floyd’s death and the ongoing movement for racial justice also demonstrated how social media can be a crucial mechanism of social change. We saw how online and on-the-ground activism can fuel each other and build momentum in ways neither can achieve in isolation. We have seen in the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement, and more specifically the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter, a new and powerful approach to using social media that goes beyond symbolic “slacktivism” and performative allyship to mobilizing people for social and cultural change.[4]

In this essay, we use empirical data to support a theoretical model that illustrates how contemporary movements can use social media to build awareness, educate, and most importantly, promote the kinds of offline action that can lead to deeper structural change. In this case, BLM effectively leveraged social media to fuel and facilitate mass protests and broaden social awareness. In 2020-21, we have seen this begin to inspire deeper social, cultural, and legal change, in ways that previously felt like distant hope.

Americans increasingly use social media for political engagement in a “digitally networked public sphere” that has come to shape social movements.[5] Even before George Floyd, more than half of all Americans participated in some form of political or social activism on social media, and 32% used social media to encourage others to take action on an issue that was important to them.[6] Furthermore, 69% of U.S. adults report that social media is very or somewhat important for getting elected officials to pay attention to issues, while a similar share (67%) say these sites are at least somewhat important for creating sustained movements for social change.[7]

Beyond individual activism, the most influential contemporary movements have also worked substantially online to bring awareness to issues, to highlight social and cultural inequities, or to help change behavior.[8] Some larger movements, like #BlackLivesMatter, #MeToo, and #OccupyWallStreet, attempt to do all three. #ArabSpring and later #Egypt were used to spark protests across different countries in the Middle East and brought international attention to popular demands for democratization.[9] #GivingTuesday encourages people to donate to charity after spending money on Black Friday and Cyber Monday.[10] #LoveWins commemorates the ruling by the Supreme Court on same sex marriage in 2015,[11] and #Ferguson remembers the failure to indict the officer that killed Michael Brown.[12] Use of the internet linked and coordinated these various, decentralized uprisings and distinguished them from traditional predecessors such as the 1960s Civil Rights movement.[13]

While online social movements can scale up quickly and execute their mission without the foundational work of building organizational capacity,[14] they are nonetheless vulnerable. They tend to follow a boom and bust cycle, with notable spikes rarely lasting more than a few days.[15] As an “attention economy” driven by viral content,[16] social media activism requires minimal levels of commitment.[17] Users are accustomed to “liking” or retweeting viral content every day, but their support usually does not require long-term commitment or action.[18] Other vulnerabilities make it difficult for online movements to meet their long-term goals or inspire sustainable and long-lasting change. For example, they are often leaderless or have too many leaders to effectively coordinate goals.[19] Thus, compared to traditional social movements, contemporary movements may lack both the culture and infrastructure needed to make collective decisions, leaving them less well equipped to adjust strategies or negotiate demands.[20] At a more fundamental level, social media’s corporate infrastructure makes such movements vulnerable to surveillance, co-optation, and censorship.[21] For example, law enforcement agencies commonly use sophisticated technologies to anticipate, monitor, and disrupt organizing efforts.[22]

Despite these vulnerabilities, BLM has managed to tie its significant online outreach and activism to the kind of grassroots organizing and offline action that have made traditional social movements successful. Like traditional movements, BLM has also engaged in long-term planning and leveraged strong institutional commitment and connections to community organizations, nonprofits, labor unions, and student groups developed over years of localized action. This hybrid structure has allowed BLM to build a dynamic model of online and offline activism capable of structural change.

Table of Contents Show

I. Methodology

We use Twitter data to show how BLM has translated the persistent and viral nature of police violence and Black death into an opportunity to change minds, hearts, and the baseline understanding of inequality.[23] We have been studying the #MeToo movement[24] and the #BlackLivesMatter movement as part of a research collaboration between the Massive Data Institute and the Gender+ Justice Initiative at Georgetown University. We have seen in both movements the power of online and offline activism working in tandem to make persistent forms of violence more visible and less acceptable.[25] We began this project focusing more specifically on BLM to explore how social media was being used for the movement for racial justice and how it may be leading to more lasting structural change.

Studying millions of unique online posts is a massive data undertaking, so we narrowed the scope of this current project to focus on one online platform, Twitter, which is heavily used for activism and political participation. Twitter is also ideal for this project due to the demographic diversity of its users, its focus on hashtags, and the common retweet function that allows users to rapidly share their views and other information. Overall, we collected over 41 million tweets with the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter that were posted between January 1, 2019 and November 15, 2020.[26]

We analyzed these tweets in three stages. In the first stage, we analyzed the frequency of tweets with the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter from January 1, 2019 until November 15, 2020 to explore how the volume of online activity fluctuated and the extent to which the activity seemed to correlate with major events. In the second stage, we examined the online activism that followed the death of George Floyd in 2020. We focused more specifically on the hashtags that co-occurred in the same tweet with the central movement hashtag #BlackLivesMatter between May 1 and August 31, 2020. We began this stage by reviewing the 1,000 most frequently used co-occurring hashtags as a team to search for overarching themes. This qualitative review provided clues that helped us understand how the central hashtag #BlackLivesMatter was being utilized. We used these clues to construct a typology of the most frequent co-occurring hashtags. The high-level themes that emerged include: (1) BLM Drivers, (2) Global Protests, Activism, and Allies, (3) Next Level Activism, (4) Legal Action and Accountability, (5) Amplifiers such as Backlash and COVID, and (6) a catch-all category of significant events, popular culture figures, and media references.

In stage three, we organized these major categories into subtopics that helped tell a more complete story of the online activity taking place. This stage was an iterative process that involved individual additions and deletions of hashtags in each sub-category followed by group conversations to ensure agreement. In November 2020, we expanded the data to also include the prominent co-occurring hashtags between September 1 and November 15, 2020. We then repeated the coding process to assess whether any additional categories emerged based on these additional tweets. For example, the updated data included many more co-occurring hashtags related to the 2020 election. Finally, we identified frequently occurring hashtags in tweets that did not contain any of the co-occurring hashtags already identified, and added additional hashtags to the different subtopics as needed. Based on this third stage of analysis, we constructed a theoretical model that explains how social media movements like BLM can convert hashtag activism into broader social awareness and ultimately cultural and legal change.

II. BLM: From Contemporary Social Movement to Structural Change

A. Black Lives Matter as a Social Media Powerhouse

Dating to 2013 as a Twitter response to George Zimmerman’s acquittal for the killing of Trayvon Martin, the BLM movement has been the largest and longest-lived social justice movement initiated on social media.[27] Black people were early adopters of Twitter and Instagram, and the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag was widely and effectively used to document police and vigilante violence toward Black people.[28] The BLM movement also demonstrated its ability to translate social media activism into on-the-ground activism when it organized demonstrations in Ferguson, Missouri to protest the killing of Michael Brown and what it stood for: the systematic targeting of Black people by a militarized police.[29] Following Ferguson, the BLM movement began to formulate specific institutional and policy goals to end state violence against Black people. That was years before the world had heard of George Floyd or witnessed his death at the hands of Minneapolis police officers.

The BLM movement has been so effective that years before the conflagration of 2020 its work was described as leading the “Third Reconstruction,” the latest mass mobilization for racial justice and a new vision of structural inequality.[30] The overarching structure of the movement is a decentralized network of activists with no formal hierarchy.[31] The movement includes an official organization, Black Lives Matter Global Network Foundation, Inc. with chapters around the world, as well as a broader network of activists and supporters of racial justice who are not affiliated with the formal organization.[32] In the seven years since its founding, BLM has only become more sophisticated at using the internet to frame, formalize, and advance their agenda.

The renewed attention and activism that George Floyd’s death inspired in 2020 was possible because video images and social media were effectively harnessed to transform injuries and outrages that were well-known within Black communities into injustices that could no longer be ignored by the broader population. Social media users leveraged the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter to shift the narrative and tell a story that was not being shared in mainstream media. The combination of a viral video and hashtag narratives made it easier for other users on Twitter to search, link, and interact with one another via the hashtagged word and to share stories and information related to it.[33]

Indeed, BLM had effectively laid the groundwork for the wrenching video of Floyd’s death to serve as a tipping point. It did this through online activism and years of building a policy agenda aimed at eliminating systemic racism in education, housing, employment, health care, public services, criminal justice, and policing. None of this was new, but it took repeated tragedy and a perfect storm to get a broad spectrum of people to care.[34]

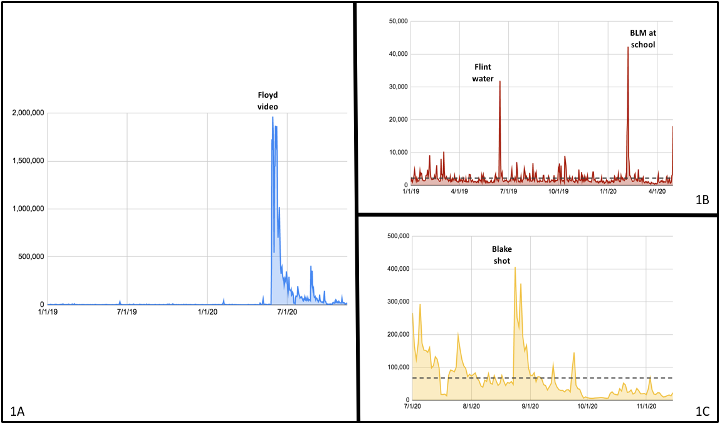

Figure 1 illustrates our first stage of analysis that traces the tweet activity of the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter from January 1, 2019 to November 15, 2020. Although 1A suggests one significant boom for the hashtag, followed by a significant bust, a closer look at Figures 1B and 1C shows both the longevity of the movement conversation and that 2020 was very different for #BlackLivesMatter. The volume was much greater and the momentum lasted longer, even months following the primary spike, which is atypical for social media activism.[35]

Figure 1: Volume of Tweets and Retweets using #BlackLivesMatter, January 1, 2019 – November 15, 2020.

Figure 1B shows the baseline between January 1, 2019 and the end of April 2020, where the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter was tweeted on average over 2,100 times per day, with a few short-lived spikes that returned back to the usual activity after just a day or two. The most significant #BlackLivesMatter activity prior to May 2020 occurred June 14-16, 2019, when the daily tweet count reached over 30,000, and February 5-8, 2020, when it reached over 40,000. Both of those spikes came in reaction to events important to the social movement for racial justice. For example, on June 13, 2019, Michigan state prosecutors announced they were dropping all charges against the Flint city officials accused of contaminating the city’s drinking water.[36] BLM had explicitly connected the Flint water supply crisis to environmental racism as well as state indifference and violence.[37] At almost the same time, in mid-June 2019 the disciplinary trial of Daniel Pantaleo, one of the officers who killed Eric Garner, came to an end,[38] and on June 13, the Washington Post reported that an attorney for the NYPD Union had claimed that Eric Garner died due to obesity.[39]

Similarly, February 3-7, 2020 was billed as Black Lives Matter at School Week and was endorsed across the country by school districts and the largest teacher’s union, the National Education Association.[40] On February 7, the Boston Police Union President spoke out against BLM events in Boston schools and asked the Boston Teachers Union to pull its support.[41] On that day the daily tweet count for #BlackLivesMatter reached over 40,000.

The dramatic levels of activity in May and June 2020 did not come out of nowhere. By the beginning of May 2020, #BlackLivesMatter was not a new hashtag, but rather an established one. At the beginning of April were the first widespread reports showing that African Americans were disproportionately contracting and dying from the coronavirus,[42] and daily tweets of the hashtag briefly rose to over 18,000. Then on May 5, the video of Ahmaud Arbery’s February 23 murder was released on YouTube[43] and on May 6 the hashtag was used over 38,000 times. On May 7, with the arrests of Gregory and Travis McMichael,[44] that number rose to over 62,000. On May 25, George Floyd was murdered and his brutal death went viral on social media.[45] The significant Twitter spikes prior to May 2020 pale in comparison to the activity of #BlackLivesMatter in the first month following George Floyd’s killing. The day after George Floyd’s death, the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag was used approximately 390,000 times and on May 27, it was tweeted more than 1.7 million times. During the two weeks following Floyd’s death, the daily use of the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag hovered between 1.3 and 2 million tweets and retweets per day. During this time, the average volume was over 500,000, a daily average that is more than three hundred times greater than the daily average in the prior year and a half.

In July 2020, daily tweets fell below 200,000 over multiple days for the first time since George Floyd’s death as protest activity also declined. While the June spike and the drop in July is eerily similar to #MeToo and other social media movement trends, what is notable in this instance is how long the spike lasted and how high use of the hashtag remained, even through November 15, 2020. In Figure 1C, between July and November, the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter was tweeted on average over 67,000 times per day, a drop from the prior two months, but significantly higher than the pre-Floyd volume which averaged approximately 2,100 tweets per day. The most significant spikes during this period were when Jacob Blake was shot seven times on August 23 by a police officer in Kenosha, Wisconsin, and during the protests that followed, when a teenage counter-protester armed with an assault rifle killed two protesters.[46] Then, on August 26, as protests continued in Wisconsin, a four-day event to protest the killing of Breonna Taylor ended in Kentucky with the arrests of dozens of protesters engaged in a sit-in.[47] After the protests for Breonna Taylor, #BlackLivesMatter hashtag activity died down significantly through the fall. The decline itself was not surprising given the focus on the US presidential election, but it is noteworthy that even the lower daily volume between September 1 and November 15 remained substantially higher than pre-George Floyd levels.

This #BlackLivesMatter hashtag activity demonstrates the influence of BLM in using its social media presence to change the conversation about race and racism in the United States, and to help define how people around the world respond to police violence and other forms of racial inequality.[48] In the following section, we provide a closer empirical analysis of this #BlackLivesMatter activity on Twitter. This data analysis enabled us to build a conceptual model to better understand how contemporary social movements can harness the power of social media to create widespread social awareness, new cultural understandings, and ultimately legal change.

B. Tweets and Streets: The Dynamic Relationship between Online and Offline Activism

Focusing in on the period between May 1, 2020 and November 15, 2020, Figure 2 illustrates the core topics of BLM-related conversation on Twitter. This figure shows a circle for each hashtag that co-occurs with #BlackLivesMatter. Larger circles occur more frequently, while smaller circles occur less frequently. The colors of the circles correspond to the high-level topics. The most frequent single hashtag used between May 1 and November 15, 2020 is #georgefloyd, appearing in over 1.1 million tweets.[49] The most frequent topic—BLM drivers (red)—includes subtopics that relate to the animating mission of BLM: exposing police violence, raising awareness of racism and inequality, and identifying victims. The next most frequent topic is protests, allies, and solidarity and activism (yellow). Figure 2 helps show how, in a moment of opportunity, BLM was able to use its already substantial presence on social media to frame the conversation (red), organize protests and inspire solidarity and activism (yellow), facilitate “next level” activism online and offline (green), and push for accountability and policy initiatives on racial justice (blue).

Figure 2: Major Topics of Discussion on Twitter in Posts Containing #BlackLivesMatter

While outrage was already brewing, it was clearly the video of George Floyd’s murder that ignited a sustained series of protests and other offline events calling for racial justice and police accountability that worked in tandem with social media to renew and fuel a broader movement. Figure 2 helps illustrate the dynamic interaction between online and offline activity. Social media served at least three key roles for BLM following the death of George Floyd. One, it helped spread links to the video to increase its visibility. It also leveraged the viral video to spark increased activism. Second, it quickly disseminated the information that led to and allowed for responsive collective action. Through daily communications, organizers effectively reached and coordinated newer activists and others who traditional movements may overlook. Third, it also helped capture some of the mass mobilization as well as police abuse at the protests that enabled the movement to adapt and respond in turn. This allowed activists to offer a narrative of events that could have taken much longer for mass media outlets to capture and share.

The scope and persistence of the offline activism was only possible because it was coordinated online. Across the globe, individuals from all races, ages, and socioeconomic status took to social media and the streets to collectively express their outrage and solidarity. Our hashtag analysis suggests that BLM found an expanded network of organizational allies in the LGBTQ+ rights movement, the women’s rights movement, and in the movements of other marginalized groups. Corporations, universities, members of congress, and other high-powered institutions also spoke out and pledged to do their part in dismantling systemic inequality. Social media was used to facilitate it all, highlighting the breadth and depth of the growing community of supporters.

Like other movements, broad participation in Black Lives Matter was further fueled by the broader social-political context and key events. In this case, intense political division, the spread of COVID-19, and the resulting economic turmoil created the conditions for a perfect storm that predated George Floyd.[50] Americans faced historic unemployment, political distrust, and the strain of intense isolation after many weeks of quarantine.[51] This perfect storm was unleashed by George Floyd’s death, and the dynamic online and offline activism that followed paved the way for an even deeper racial reckoning. Activists used this hybrid online and offline approach to frame that reckoning, to organize money donations, die-ins, and mural paintings; they tore down statues, circulated petitions, and proposed policies. Professional athletes and politicians took a knee.[52]

C. A Theory of How to Move from Social Media Movements to Structural Change

Figure 3 presents a theoretical model using our typology of hashtags that co-occur with #BlackLivesMatter. This model leverages the Twitter data to illustrate what we see with BLM, but it also captures a more generalized process through which contemporary social movements can create long term systemic change. We illustrate our general theory of how social media movements evolve vertically on the left. We then use the model to demonstrate how our empirical analysis and resulting hashtag typology support and further delineate how this process has occurred for BLM.

The gray box at the top of the figure is the social movement, in this case #BlackLivesMatter. The red boxes are the drivers that represent the motivating issues of the movement, and include the hashtags that drive the social media conversation. For BLM, this includes the overarching goals of exposing police violence, humanizing victims, and raising awareness of racism and inequality. Following the death of George Floyd in May 2020, the movement picked up enough momentum to both spark and coordinate mass protests across the globe with the broad support of individuals, institutions, and a multitude of intersectional and allied movements. This is illustrated by the yellow boxes. Both the drivers and the initial support capture the awareness phase of the movement.

Once the social media conversation went “to the streets,” these highly visible protests garnered consistent media attention, continued to fuel the social media conversation, and translated to changes in the way many people felt and the urgency with which they acted.[53] This marks an evolution beyond the social awareness generated by a movement to cultural change, which then sets the stage for further institutionalized legal and policy change.[54] What started as a hashtag to raise social awareness of racialized police violence launched a widespread racial reckoning that evoked solidarity and activism, including concrete actions like economic mobilization, Black empowerment, and heightened political participation; these profound effects are indicia of cultural change.

While the movement from social awareness to cultural change is an accomplishment in itself, it also explains “how” the social media movement can move closer to the legal and policy changes that have the potential to institutionalize its goals and create a more lasting impact on the Black community and society more broadly. The blue boxes at the bottom of the model illustrate some of the overarching legal and policy aims of BLM that can solidify the cultural momentum into the institutional change needed to dismantle deeply entrenched systemic racism.[55] The changes highlighted in the online movement focus on justice and accountability for victims of police violence, policies that reimagine policing, and broader systemic reform required to change the lives of Black people, including equitable education, housing, economic opportunities, and health care.

Lastly, the orange boxes are “amplifiers” that remind us that social movements are not alone in social media conversations. In 2020, the global coronavirus pandemic fueled conversation and activism. It is also important to note that not all tweets with the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter were supportive of the movement or its goals. This is consistent with other online movements where other parties interested in the same topic emerge to wield their own power, often in opposition to the movement in the form of backlash.[56]

Figure 3, the Anatomy of BLM: A Typology of Hashtags that Co-Occur with #BlackLivesMatter

III. Getting from Social Awareness to Cultural Change

Social justice movements are not just about the activism and mobilization of those who support a cause. They are also about educating those who do not yet support a cause, but might under the right circumstances. Evan Wolfson, the founder of Freedom to Marry and the architect of the campaign for marriage equality, has said of the decades-long effort to constitutionally protect same-sex marriage that although litigation was always central to their strategy, they “had to think and work beyond litigation and law.”[57] According to Wolfson, it was not new legal arguments that were needed, but “getting people to open their hearts, change their minds, and be willing to see what was always there.”[58]

Legal change requires cultural change and cultural change requires learning to see things differently. Freedom to Marry and their Twitter campaign #LoveWins humanized LGBTQ+ people, told their stories, and taught others to understand their struggle and to share their goal of having their love recognized.[59] Similarly, BLM has long used their platform to build social awareness by humanizing the victims of police violence, by educating the public to better understand anti-Black racism and inequality more broadly, and by encouraging solidarity around the goal of racial justice. This foundational education and awareness allowed BLM to capitalize on the attention and intensity of the protests and the social media discussion they generated to expand their base of allies, broaden the cultural reach and understanding, and inspire supporters to be activists. In essence, they were getting people to see what was always there—a more systemic form of racial inequality.

The breadth of the protests and the depth of active commitment to the movement also inspired a set of tangible results, what we term next level activism: economic collective action, Black empowerment, and political participation. First, it put pressure on consumers, corporations, and organizations to not only support racial equality but to financially commit to it, inspiring fundraising, boycotts, and corporate economic support for the Black community.[60] In addition, BLM has continued to speak to and work for its core supporters and part of the cultural change we see online is the emphasis on Black empowerment and solidarity within the Black community. Lastly, BLM inspired increased participation in the political process at the same time that the cultural and political divisiveness of the 2020 election amplified attention to the movement.[61]

Part A explores the first stage of cultural change which involves educating people about victims, the harms of police brutality, and broader issues of racism and inequality. Part B discusses how the movement activity can evolve from primarily raising social awareness online to building alliances and solidarity, and mobilizing supporters to protest and be actively invested in change. Part C addresses the next level of activism which focuses on more tangible economic and political commitments while the core community expresses pride, power, and a central role in the continuing struggle for equality.

A. Normalize Equality: Raising Social Awareness

One aspect of BLM’s success as a movement is that its core concerns of exposing police violence, naming and humanizing victims, and highlighting racism and inequality have stayed consistent and are highly adaptable—they are used not only to raise awareness in individuals but to deepen cultural understanding. The protests and the online conversation taught people to feel differently and see differently than they had before. This Part uses our data to explain how BLM effectively raised global awareness of those core concerns, which are drivers of movement activity.

1. Humanizing Victims

Giving names and identities to people, placing them in a family, learning about their story, their hopes, and their hardships—these are the fundamental ways that strangers come to matter to us. The online conversation about Black lives since George Floyd’s death highlights the centrality of his name and the names of many other victims in raising awareness, cultivating empathy, and encouraging solidarity with the goals of the BLM movement. Identifying victims not only creates empathy at the individual level, but it also helps create a historical record and cultural change.

By far the largest group of hashtags that co-occurred with #BlackLivesMatter between May and mid-November 2020 were hashtags of victims’ names—primarily victims of police violence but some victims of vigilantes or others who died in violent and racialized circumstances.[62] Included in this category are expressions of condolence associated with victims, such as #rip or #restinpower.[63] Hashtags associated with victims’ names co-occurred with #BlackLivesMatter over 1.8 million times during the six-month period. Figure 4 shows the hashtags related to the victims that occurred at least 30,000 times. The hashtag #georgefloyd and variants of his name co-occurred with #BlackLivesMatter well over a million times and far more than any other single hashtag.

Figure 4: Victim Identification Hashtags that Co-Occur with #BlackLivesMatter

George Floyd did not start the nation’s racial reckoning and he will not end it. Yet his name became a vehicle for thinking about Black lives and the inequalities of Black deaths; in 2020, his was the central name around which the Black Lives Matter movement raised awareness and inspired solidarity and activism. An important aspect of George Floyd’s prominence among victims is the video that was taken of his murder. The intimacy, length, and brutality of the video generated broad empathy and outrage. It also contributed to the synergy between awareness and activism; the social media and mainstream media heavily reported Floyd’s death, the protests and online activity continued to focus on him, and the media continued to cover his life and humanized him further.[64]

In one sense George Floyd’s name—and the human dignity associated with it—served as a stand-in for and a memorial to the countless unarmed Black people who have died at the hands of police before him and those who would die in the future. Yet, as Figure 4 shows, the online conversation also named and acknowledged many other victims of racial violence. The hashtags of victims’ names are noteworthy for including not only the lives lost to police violence during the spring and summer of 2020—especially Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, Tony McDade, Rayshard Brooks, Andres Guardado, and Jacob Blake—but for also highlighting the names of Black victims whose deaths had contributed to building a racial justice movement online and offline: Emmett Till, Trayvon Martin, Eric Garner, Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, Sandra Bland, Alton Sterling, Philando Castile, Matthew Tucker, Pamela Turner, and Elijah McClain. In this way, the hashtags reclaim the lives, deaths, and humanity of those that preceded George Floyd.

2. Racism and Police Violence

These two significant groups of hashtags are BLM drivers because they capture the anger over police treatment and a fuller understanding of the relationship between police violence and the racial inequality that produces it. Hashtags that invoked police entities and the indignation they inspire co-occurred with #BlackLivesMatter approximately 350,000 times during the relevant period, and hashtags about racism and inequality co-occurred over 330,000 times.

The hashtags that encompass police entities and violence call out many specific police departments, but focus heavily on distrust and brutal treatment. The highest co-occurring hashtags in this category were #acab, representing the slogan “all cops are bastards,” which was tweeted over 90,000 times, and #policebrutality, which was tweeted approximately 82,000 times. This category also speaks more broadly to #policeviolence, including various police shootings, over-policing at protests, #murder, and #unarmed.

The racism and inequality hashtags capture a set of topics that indicate a shift in thinking about racism within the larger culture, encompassing in addition to #racism itself, #slavery, #whiteprivilege, #whitesupremacy, #genocide, the #kkk, the #confederateflag, #statues, #systemicracism, as well as references to specific instances or forms of racism such as #amycooper, #kylerittenhouse, #karens, and #proudboys.

B. I Can’t Breathe: Inspiring Solidarity and Widespread Activism

This subsection uses our data to explain how BLM effectively translated the increased social awareness into recruiting allies, organizing protests, and building solidarity around activism for racial justice. The three categories in yellow in our model worked together to shift the cultural understanding of racism by exploiting the synergies of online and offline activism.

1. Protests and Allies

In 2020, the widespread activism in support of the movement was fueled by the broader social-political context and key events. In this case, intense political division, the pandemic, and the resulting economic turmoil created the conditions for mass protests. Across the globe, individuals from all races, ages, and socioeconomic status took to social media and the streets to collectively express their outrage at George Floyd’s murder and the many other victims of police violence. There were multiple protests in every U.S. state and cities around the world.

Our data show that between the beginning of May and mid-November 2020, there were over 1.1 million #BlackLivesMatter posts with hashtags specifying one of 208 global locations, and over 800,000 posts mentioning one or more protest-related hashtags. Some of the locations frequently mentioned include #kenosha, #portland, #seattle, #minneapolis, #atlanta, and #chicago. The most common protest-related hashtag was #dcprotest, which was used over 130,000 times during this period. Other common protest hashtags include #protests2020, #georgefloydprotests, #portlandprotests, #nycprotests, and #blmprotest.

The protests were possible on the scale they achieved in part because BLM had already raised awareness and cultivated allies. By inspiring intersectional and other allied groups as well as new supporters, BLM was able to mobilize allies quickly to build on the early activism. The co-occurring hashtags suggest that BLM found an expanded network of organizational allies in the LGBTQ+ rights movement, the women’s rights movement, and in the movements of other marginalized groups. For example, the most common hashtags in the category of intersectional and allied movements reflect the global expansion of BLM itself, such as #blacklivesmatteruk; the intersectionality of the movement, reflected in hashtags like #blacktranslivesmatter; the fellow travelers of #lgbtq, #metoo, and #indigenouslivesmatter; as well as digital activism allies like #anonymous.

2. Solidarity and Activism

Activism can take many forms, and the protests were one very visible kind of activism. The hashtags in the solidarity and activism category embody the animating ideas, movement slogans, and demands for equality that were prevalent in the online conversation, repeated at the protests, and ultimately embedded in the national vocabulary. Some of the hashtags are responses to the drivers of the BLM campaign. For example, the responses to racism and inequality appear in the activism category as calls for action on these topics: #noracism, #endracism, and #stopracism. In addition to calling for #justice and #equality, the activism hashtags also include many expressions of solidarity in hashtags that seek to counter hate and division with #love and #solidarity.

Another set of common hashtags that both built solidarity and motivated activism were the powerful phrases that became movement slogans. These animating ideas were often responses to core BLM concerns. As one example, naming individual victims of police violence was crucial to developing awareness and empathy, but it was the focus on humanization—the activist admonition to #sayhername and #saytheirnames—that became one of the iconic phrases of the movement. Those hashtags did double duty: they helped humanize the victims and they helped translate that sense of shared humanity and outrage into protests and activism. We coded these phrases as solidarity and activism because they became among the most common chants at protests and symbolic of the movement more generally. As movement slogans they also entered the common parlance, familiar even to those who neither participated in nor supported the BLM cause. That discursive effect is part of what creates cultural change.

Perhaps no BLM phrase has been as effective at raising awareness and inspiring solidarity and activism as #icantbreathe. It is poetic in its ability to convey so much meaning with so few words. It elicits pain, solidarity, and an invitation to participants and allies to learn to see things differently. The phrase succinctly captures the effects of police violence and racism at the same time that it stands for an insistence that people acknowledge the Black experience of suffocating from racism so pervasive and deeply ingrained as to be almost invisible. Part of the power of #icantbreathe as an iconic phrase was the way it linked allies and participants in its complex meaning.

Given the power of the phrase #icantbreathe, it is not surprising that it was the single most common hashtag in this broad category, tweeted with #BlackLivesMatter more than 300,000 times during the relevant period. Figure 5 shows the solidarity and activism hashtags that occur at least 30,000 times. In addition to movement slogans, other commonly co-occurring hashtags represent resistance to racism and violence and general demands for justice, such as #nojusticenopeace, #justice, #enoughisenough, #normalizeequality, and #taketheknee, which encourages people to kneel in solidarity.[65]

Another important form of BLM activism that occurred both on Twitter and in public squares across the U.S. was the debate over the meaning of national symbols, holidays, and monuments. This debate is evident in the hashtags, with many posts referencing various statues or reacting to Trump’s use of the July 4th holiday in 2020 to condemn BLM protesters as “anarchists, agitators, and looters.”[66] The popular removal or defacement of confederate monuments as part of BLM protests and activity is a powerful example of the impact of BLM activism on cultural understanding. These monuments have been a staple of American public space for more than a century and a half and have been fought and defended for as long. BLM activism changed the politics and meaning of these monuments broadly enough that over 130 have come down since George Floyd’s death.[67]

Figure 5: Solidarity & Activism Hashtags that Co-Occur with #BlackLivesMatter

Taken together these co-occurring hashtags continue to convey an acute awareness of racism and police violence. They also do more than this; they attest to a change in the broader culture that brought together diverse allies, widespread protests, and intergenerational activism for equality and police reform. This cultural shift marks a growing understanding among the general public that state-sanctioned violence is a pervasive part of Black life.[68]

C. No Justice No Peace: Next Level Activism

The education, allies, and activism catalyzed by the BLM protests translated not only into changing hearts and minds, but also into next level activism, with more concrete financial and political support which could be used to help begin to unroot deep systemic inequalities. As cultural change becomes more widely accepted it puts pressure on celebrities, corporations, and organizations to make public and economic commitments. It also inspires political debate and activity. And in the case of BLM, it inspired a robust conversation about Black empowerment, pride, representation, and resilience.

1. Economic Collective Action

As the unrest intensified in the streets, and BLM gained more supporters seeking racial reckoning in their schools, workplaces, and communities, economic demands followed. When social movements are able to shift the cultural norms sufficiently, corporate endorsement and donations are a common response. For example, dozens of companies, including Visa, Marriott, and Target, among others, endorsed marriage equality using the Freedom to Marry hashtag #LoveWins.[69] Companies now regularly sponsor annual Pride Parades and create unique brands and products celebrating LGBTQ+ equality.[70] As part of the broader #MeToo cultural reckoning, several companies issued statements supporting harassment-free workplaces.[71] For BLM, the largest economic discussion on Twitter was centered around a global fundraising campaign to match the million dollars that BTS, the Korean pop band, donated to the BLM movement. Their campaign sparked hashtags ranging from #matchamillion and #bts to #btsarmy. After giving $1 million to BLM, its fan group matched that by donating $1.3 million to a dozen related advocacy groups.[72]

With involvement and demands so widespread, the culture was shifting and it became impossible for powerful institutions to maintain ignorance and companies began to take a public stance by issuing statements of solidarity. A wide variety of corporations also contributed financially to the movement, either to the Black Lives Matter Global Network Foundation or to other anti-racism organizations.[73] Some corporate financial commitments did not designate recipients or dedicated the money to initiatives internal to the company. Walmart pledged $100 million for an internal racial equity center.[74] Bank of America announced a $1 billion commitment to programs that help “communities of color address economic and racial inequality.”[75] PepsiCo pledged $400 million to initiatives that “lift up Black communities and increase Black representation” at the company.[76] Apple’s announced a “Racial Equity and Justice Initiative with a $100 million commitment.”[77] And Comcast announced “a plan to designate $100 million to fight injustice and inequality against any race, ethnicity, gender identity, sexual orientation or ability,” with much of that money going to internal projects.[78] The point is that there was scrutiny of how corporations were choosing to answer consumer demands that they, too, pay attention and put their money behind their mass emails and public broadcasts.

2. Black Empowerment

As Black Lives Matter Co-Founder Alicia Garza has said, “Black Lives Matter has come to signify a new era of black power, black resistance and black resilience. For black folks, this is our renaissance.”[79] Our data support this assertion. As part of the cultural shift toward racial reckoning, the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag has also been used widely to express Black pride and power. Figure 6 shows the highest frequency hashtags—those occurring at least 10,000 times—related to Black empowerment. We see the emphasis on being Black and celebrating being Black in hashtags such as #black and #juneteenth. Other relevant hashtags not shown in Figure 6 focus on Black women and girls, such as #blackwomenmatter and #blackgirlsrock, and on the strength of being Black, like #blackpower. This embrace and pride of identity reinforces the pride in culture and the social inequity. This empowerment strategy is directly connected to concrete, on-the-ground activist efforts reaching far beyond social media presence.

Figure 6: Black Empowerment Hashtags that Co-Occur with #BlackLivesMatter

According to Black Lives Matter Global Network co-founder, Opal Tometi, Black-centered organizations such as the Black Alliance for Just Immigration—which she used to lead—are utilizing a mutual-aid model of collecting resources, such as money, food, or different skills within the community.[80] Many contemporary activists see this type of self-reliance and accountability as one of the most effective and empowering ways to counter systemic barriers.[81]

The Black empowerment hashtags portray community demands to uplift and be uplifted, specifically through action-driven solutions. This can be seen in tweets such as #blackexcellence and #blackownedbusinesses. For example, a form of economic mobilization was referenced as #blackoutday2020. At its core, this was Black empowerment where Black consumers collectively pledged not to make purchases, unless the money was directed towards black-owned businesses.[82] Similarly, #blackouttuesday was an effort begun by Black executives in the music industry to disrupt business as usual in an effort to reflect on the role of Black artists in generating industry profits; it quickly became a much wider action.[83] These empowerment strategies reflect the unity, solidarity, and collective efficacy that can speed the Black community towards broader goals of policy and legal change, and increased political power. One recent example that overlaps with political participation is the acknowledgement of the role of Black voters in the 2020 election, the Black candidates running for office at every level,[84] and the way Black women, like Stacey Abrams and Kamala Harris, are redefining the Democratic party.[85]

3. Political Participation

Contemporary activists recognize the importance of participating in the political process as a way to create and maintain lasting change. This includes voting in elections, mobilizing voters, and even running for office. But it also includes online political participation. We see this in our hashtag analysis, with a substantial number of political hashtags used alongside the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter. This was especially true in the run up to and immediate aftermath of the 2020 U.S. presidential election. The top six co-occurring hashtags provide a good indication of the category: #trump, #democrats, #vote, #maga, #resist, and #bidenharris2020. In addition, there were a variety of negative tone hashtags that involved Trump, such as #trumpdictatorship, #trumpmeltdown, and #bunkerboy. Also captured in the political participation category were many references to specific political issues, both national and international, as well political ideologies or theories, such as #farright, #leftwing, #fascism, #marxism, and #qanon.

Beyond admonitions to vote and get-out-the-vote campaigns, we grouped political participation with next level activism because social media also allows activists to interact with lawmakers directly, given that most legislators have Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook accounts, and many are active participants themselves.[86] For example, Black and brown activists like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Lucy McBath, and Sybrina Fulton are entering the political sphere dedicated to changing politics and pushing policies for racial justice. Representative Ilhan Omar remains a supporter of disbanding the Minneapolis Police Department. As we increasingly see with elected officials, she discusses her position on Twitter, stating that “A new system will allow officers to address the most dangerous situations and serious crimes that our residents face, while ending the criminalization of poverty and disproportionate violence against Black and brown communities.”[87] The growing demands for a wide range of legal and policy change, and the growing support of these policy shifts communicated online, demonstrate the effective activism of political participation and the immense potential for systemic change at the local, state, and federal level.

D. Systemic Racism: Learning to See What Was Already There

As the prior sections show, social media is a virtual public sphere of information and emotion. It is also, quite literally, a spectator sport; its visuality has dramatically changed the way information is generated and exchanged, and has created a currency in images and image consumers. While our analysis is based primarily on hashtags, we appreciate the importance of image sharing on social media generally and as part of BLM activism specifically. BLM has effectively harnessed the power of social media to encourage people to “see” racism metaphorically, through effective activism. It has also used social media to allow people to “see” literally by making use of video documentation: as a source of viral content and virtual attention, of horror and empathy, and of letting the persistence and intensity of visual police violence explain systemic racism.[88]

Social media has helped to produce a new form of popular journalism and a reverse form of racial regulation as people record racially charged interactions with police.[89] Everyday citizens and protestors use their personal mobile devices to record and post interactions that have previously been routine but invisible. In doing so they provide exposure to stories of racial regulation that the news often does not cover or perspectives that cannot be captured with body cameras.[90] This visual documentation is propelled by being linked to the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag and has helped shift the narrative of police brutality and racism away from the individual to institutions and systemic practices.[91]

Visual documentation works especially well in the attention economy of social media, which helps to keep the issue of racialized police violence in the public eye, but its power comes in part from the fact that these visual images, taken together, feel like evidence.[92] In each case the video is linked to an individual with a name, but understood collectively, it is clear they happen too often to be aberrational.[93] So while police killings of unarmed Black men, women, and children are far from new, visual evidence of this violence is relatively new and the ability to transmit those images broadly and instantly is very new.[94] BLM has effectively used the exponential power of social media in conjunction with offline advocacy to not only transmit images of police abuse, but to use those powerful images to change the narrative: to make the point that these needless deaths is what systemic racism looks like. It doesn’t look like a rogue cop or someone spewing hate; it looks like ordinary police and ordinary citizens going about the business of “keeping the peace” but assuming that Black people who drive, jog, shop, play in parks, or nap in their cars are not peaceful.

Part of the power and meaning of these killings came from technologies that helped more people see them literally and see them as part of a pattern of racialized police violence. BLM activism has helped to name, remember, and dignify those victims as individuals and it has helped the rest of us see the pattern in those deaths. The movement has enabled more people to see, literally and figuratively, the violence that was there along, and that vision may also be inspiring a cultural shift in understandings of systemic racism.

IV. Looking to the Future: From Cultural Change to Legal Change and Contestation

The question remains: can the social and cultural change inspired by the BLM movement be leveraged to accomplish the broader movement goals of legal, policy, and political change to address the more entrenched problems of systemic racism?[95] While our response must be speculative, and we acknowledge that the real-world effects of contemporary social movements such as Occupy, the Women’s March, and even Ferguson-era BLM are often underwhelming, we have some reason for hope. First, since George Floyd’s death, cities have already cut billions of dollars from police budgets; school districts have severed ties with the police; multiple police reform and accountability bills have been introduced in Congress; and cities like Minneapolis have vowed to defund policing.[96] Second, although legal reforms, even serious and substantial ones, will not solve such deeply rooted problems alone,[97] the cultural shifts we have seen so far suggest that activism, empathy, and education is continuing and the slower process of understanding what systemic racism looks like in its many forms is underway. Lastly, progress on racial inequality has never been a straight line and has never been unanimous.[98] If indeed this is the Third Reconstruction,[99] the opposition will be as fierce as it was before, and we already know what that opposition looks like.[100] In this Part we offer some tentative thoughts on the possibility of legal and structural change, and conclude with a brief discussion of the sizable social media backlash to the BLM movement.

A. Possibilities for Legal & Lasting Structural Change

Learning from history, we must recognize that the current demands for racial justice led by the Black Lives Matter movement are unlikely to lead to broader policy and cultural shifts, unless the moment continues to be advanced by advocates and allies.[101] We saw the difficulty of translating activism into substantial equality with the MeToo movement, which generated greater accountability and some significant policy changes for sexual misconduct even though it has not achieved systemic changes to gender inequality more broadly.[102] For the BLM movement, the timing is ripe for such change. Not only has education and activism fostered increased support for the movement, but nationwide surveys taken after Floyd’s death also suggested that Americans’ support for the police had shifted noticeably and was declining. This held across racial groups, including white Americans, of whom 31% had an unfavorable view of police on June 3, 2020 compared to 18 percent just one week prior.[103]

The activism following the death of George Floyd has brought renewed attention to racial justice policy and other legal changes aimed at valuing and preserving Black life. Beyond the broader demands of #stopkillingblackpeople and #endpolicebrutality, a range of legal, policy, and political changes have been set forth by activists. The primary forms of legal change proposed, discussed, and advocated for on Twitter, include justice for victims, reimagining policing, and other systemic reform.

1. Justice for Victims

Justice and accountability have played central roles in the online conversation. These are specific calls for accountability for the victims of police brutality, such as #justiceforgeorgefloyd, #justiceforbreonnataylor, #raisethedegree, and #endqualifiedimmunity. The hashtag #justiceforgeorgefloyd was used to demand the arrest, charge, and conviction of Derek Chauvin and other officers involved in the killing. These hashtags were also commonly used to circulate petitions to put collective power behind the demands for justice. For example, a petition for George Floyd shared across social media platforms had over 19 million signatures as of December 2020, while the petition for Breonna Taylor had been signed over 11 million times.[104]

These demands for justice led to the conviction of officer Derek Chauvin, a rare case of accountability in a world where police brutality against Black bodies so commonly results in no consequences for perpetrators. BLM activism helped make this a reality. Millions across the world witnessed the intense nine-minute murder that occurred in broad daylight in front of a crowd of onlookers who begged Chauvin for mercy. While Derek Chauvin become a household name and his badge number #1087 was tweeted thousands of times, there are countless other cases in which victims receive no justice or legal accountability, including Breonna Taylor. And even other famous videos of infamous police violence, like that documenting the beating of Rodney King, did not result in convictions. This is where BLM’s work, online and in the streets, has had an impact—it has begun to change the way people think about and see racism; it allowed jurors to see in that video a person being murdered rather than a police officer doing his job. It also highlights the importance of seeking, in addition to individual accountability, deeper legal and policy changes that will both prevent Black men, women, and children from being dehumanized and brutalized by the police, and enforce penalties when dehumanization and brutalization occur.

2. Reimagining Policing

Following George Floyd’s death, activists used many hashtags to demand changes in the way we think about policing in the United States. We grouped these hashtags into a category called reimagining policing, which includes the hotly debated strategies of police reform, defunding the police, and police abolition. Figure 7 shows the highest frequency hashtags related to reimaging policing, those occurring at least 5,000 times. Police reform is the most mainstream policy response to police brutality.[105] Many advocates for racial justice, however, argue that these police reforms do not go far enough. They point out that reforms typically involve investing significantly more funding and resources into police departments.[106] Hashtags such as #defundthepolice and #8toabolition have popularized defund and abolitionist arguments, while educating social media users on the historic and racialized harms of police departments, and illuminating the failure of prior police reform efforts.[107]

Police reform proposals typically focus on institutionalizing police accountability and incremental steps to limit officers’ use of force. For example, the hashtag #8cantwait was developed and shared broadly on social media with an infographic calling for specific police reforms such as banning chokeholds, requiring de-escalation, mandating a warning before shooting, and using a use-of-force continuum, among other things.[108] These policy proposals include a range of policy actions demanded at the local, state, and federal levels.[109] The philosophy behind police reform efforts emphasizes gradual change like more training, use of body cameras, the elimination of some policing techniques, and community policing, which encourages police to know a community’s residents and dynamics.[110]

Defunding police is the dominant policy change demanded alongside the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag. What is striking about the hashtag data is that the most-commonly-used hashtag by far was #defundthepolice, a strategy that until recently was considered radical. For example, #defundthepolice was used over 146,000 times, compared to #policereform which was used around 13,000 times; #abolishthepolice was used 23,000 times. “Progressive” police departments like Minneapolis are the product of police reform efforts; yet, deadly police violence still routinely occurs in these departments.[111] Thus, demands to defund the police reflect support for a divest/invest model of policing, where police budgets are cut and used to invest in other community programs. The funding would be redirected to violence prevention programs, public housing, health care, mental health services, as well as better support systems in schools instead of armed guards.[112]

While “defund the police” became popularized in the summer of 2020, the concept has been used for years by organizers seeking to minimize police budgets. U.S. Representative Ocasio-Cortez discussed this pointedly in a tweet responding to criticism of the “defund” language: “Perhaps a bad choice to your aims & focus. It’s been an excellent choice for the organizers who have been trying to prompt a national convo for years about multibillion-dollar police depts. ‘Refund’ or ‘reallocate’ didn’t do that. ‘Defund’ did. BLM had similar early resistance.”[113] Ben and Jerry’s has also taken to Twitter to support defunding the police, including educating the public about what it means.[114] While defunding may seem radical to some, a growing number of major cities have proposed or pledged to reduce police resources: Seattle,[115] Portland,[116] Los Angeles,[117] San Diego,[118] Minneapolis,[119] Chicago,[120] Philadelphia,[121] St. Louis,[122] Dallas,[123] Austin,[124] New York City,[125] Baltimore,[126] Washington D.C.,[127] Hartford,[128] and Durham.[129]

In response to demands for more aggressive changes in the criminal justice system, abolitionists take the argument one step further than defund supporters, advocating for “an end to policing long term while still addressing community needs.”[130] According to Ruth Gilmore, “Abolition is a process of building, a process of creation, a process of reimagination.”[131] The goals of abolitionists go beyond closing police departments and focus instead on changing the structure and conditions under which criminalized communities live in order to make police obsolete.[132] The overarching idea is that “if people had health care, housing and access to good jobs and education and community, there would be less crime and less need for police” in the first place.[133]

Figure 7: Reimaging Police Hashtags that Co-Occur with #BlackLivesMatter

3. Related Systemic Reform Efforts

While most of the debate around systemic reform revolves around policing and criminal justice, racial justice activists have long emphasized that “When we say Black Lives Matter, we’re talking about more than police brutality. We’re talking about incarceration, health care, housing, education, and economics—all the different components of a broader system.”[134] Myriad systems of racial subordination, centuries in the making, have led to deeply entrenched disparities that have undermined Black opportunity, hindered Black achievement, and fueled the racial wealth gap. The resulting resource disadvantage fuels broader patterns of systemic racism by blocking socioeconomic access to quality housing, education, and health outcomes, and also compounds criminal justice disparities.[135] Only broad multifaceted change that goes beyond police reform is capable of dismantling the U.S. racial hierarchy in a way that will result in meaningful change for Black people in America. These issues are discussed on Twitter with co-occurring hashtags that identify related policy areas such as #education and #medicareforall, specific legislative proposals such as #greennewdeal, and broader systemic issues like lack of diversity and inclusion in leadership such as #representationmatters.

Reparations come up prominently among the systemic reform hashtags with two related hashtags: #reparations and #reparationsnow. For years, reparations have been proposed to address the lingering wounds of slavery and centuries of racial injustice,[136] but this solution is only recently gaining traction among leaders and lawmakers.[137] The idea of reparations seemed like a pipe dream for years, as traditionally more than two thirds of Americans have opposed the idea and even President Barack Obama considered the proposal impractical.[138] However, in the midst of the current racial reckoning, the notion is beginning to garner attention and gain political legitimacy. H.R. 40 was reintroduced in January 2021 and went from being backed by 2 members in 2014 to 173 members by May 2021.[139] President Joe Biden also supports legislation to study reparations and discussed it on the campaign trail.[140] The idea of “baby bonds” have also been proposed as a solution to close the racial wealth gap.[141]

Again, even sweeping legal and policy proposals cannot change systemic racism alone. If Derrick Bell is right that racism is an “integral, permanent, and indestructible component” of American society,[142] then such proposals and all the cultural change in the world will do little good. But when we see people coming together, across racial lines, online and in the streets, to say #enoughisenough, we cannot ignore them or the inklings of change that brought them together. Small changes in feeling and perception, new ways of seeing what was already there, new understanding of what might be possible spread across enough people can sometimes result in deep and meaningful changes; and they are worth fighting for.

B. Contestation and Obstacles to Change

BLM has accomplished an enormous amount in a relatively short amount of time with its vision, strategy, and effective pairing of online and offline advocacy. But the broad support for BLM has been met with broad backlash against the movement, spurred on actively and passively by former President Trump. The backlash ranges from strategic resistance by politicians to open white supremacy among re-energized groups like the Boogaloo and the Proud Boys. It is common for movements with controversial or progressive aims to attract counter-movements dedicated to thwarting them, and this has always been true of movements for racial equality. Thus, despite progress and promise, the movement faces significant obstacles to achieving the long-term goal of broader systemic change; foremost among those obstacles are both political & social backlash. Some of the most common hashtags that co-occur with #BlackLivesMatter are associated with backlash, including twists on the hashtag like #alllivesmatter, #bluelivesmatter, and #whitelivesmatter. Many also referred to #antifa, #antifaterrorists, and #riots2020 to negatively characterize the 2020 protests as violent and dangerous.

Further, when there is energetic support for racial justice, it’s much easier for institutions and individuals to take mere symbolic action. As performative allies are swept into the movement, their superficial endorsement of racial justice can undercut deeper structural change. In fact, their allyship is performative precisely because they wrap conservative actions in progressive language or in financial commitments to organizations on both sides of racial justice.[143]

This phenomenon can be explained through the principle-policy gap where a person’s belief in racial equity in the abstract is different from their support of policies that would help make racial equity a reality.[144] When institutions and individuals who have endorsed the principle of racial equality and declared support for BLM are unwilling to act in ways that reduce racial discrimination, they highlight the harmful persistence of the principle-policy gap.[145]

The BLM movement faces two kinds of clear obstacles—the opposition of those who wish to maintain white privilege and power, and the support of those who care about racial equity only as a marketing strategy, which is to say, only to the extent that it does not cost them anything. This approach to racial justice as a zero-sum game, one often adopted by white allies, is a self-fulfilling prophecy. It decreases the likelihood of meaningful change when seemingly progressive whites are willing to express support for racial equality but are unwilling to use their power and positions to make decisions that promote equity. Lastly, even when a social movement does not face outright backlash or ineffectual support, it is always fighting a race against time and attention.

Conclusion

We know that social media movements tend to fizzle quickly, and the window for change is small. In some ways BLM has already defied the odds of online movements with its ability to inspire significant and prolonged offline action and shifts in the broader culture. Yet empirical research has shown that empathy shifts after protests and related activism and attitudes are likely to revert back, so the challenge for activists is to maintain the sense of urgency among the public and take advantage of precious opportunities for policy action when they are presented.

As Charles Lawrence puts it:

If reconstruction requires transformative law, history teaches us that too often, reform efforts have merely modified systems of racial and social control: slavery reformed to segregation, segregation to mass incarceration. Our transformation must demand laws that name and quantify the material conditions of inequality created by racism. We must demand that those conditions end. No more study commissions to tell us what we already know, no more confessions of white fragility, no more hiring a diversity consultant to sit by the door. The mistake in this moment is to ask for too little.[146]

To maintain public attention and maximize this historic opportunity, broad and popular mobilization needs to rev up rather than die down. Like the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s, the monumental swell of support may oversell how far society has shifted during this moment.

The Black Lives Matter movement must seize this window of opportunity and convince individuals, institutions, and lawmakers to support broad systemic change, using social media as a platform for activism and accountability. As our nation gets the first glimpses of life after the pandemic and the desire to “return to normal” is strong, Americans who believe that the survival of our democracy is bound up with racial equality cannot afford a return to normal or a loss of the momentum of this historic moment. We must not be shy, polite, or undersell the change we seek.

Copyright © 2021 Jamillah Bowman Williams, Naomi Mezey, and Lisa Singh. Williams is an Associate Professor at Georgetown University Law Center and received her J.D. at Stanford Law School and her Ph.D. (Sociology) at Stanford University. She thanks Meera Deo, Joshua Sellers, and other participants in the Reckoning and Reformation symposium for their valuable feedback. Mezey is a Professor at Georgetown University Law Center. She received her J.D from Stanford Law School and M.A. (American Studies) from the University of Minnesota. She notes gratitude for the support of the MDI/G+JI research collaboration. Singh is a Professor of Computer Science and Research Professor in the Massive Data Institute at Georgetown University. She received her Ph.D. (Computer Engineering) from Northwestern University. She thanks the MDI for infrastructure, technical team, project, and student researcher support. The authors collectively wish to thank Research Librarian Sara Burriesci and our dedicated research assistants: Austin Donohue, Victoria King, Lily Milwit, Sarah Nesbitt, and Julie Zuckerbrod. DOI: https://doi.org/10.15779/Z384M91B5T.

- “Slacktivist” is a pejorative term for an individual who participates in a social movement by liking or sharing social media posts promoting a particular cause. Nolan L. Cabrera, Cheryl E. Matias & Roberto Montoya, Activism or Slacktivism? The Potential and Pitfalls of Social Media in Contemporary Student Activism., 10 J. Diversity Higher Educ. 400, 403 (2017). ↑

- Zeynep Tufekci, Twitter and Tear Gas: The Power and Fragility of Networked Protest 6 (2017); see also Monica Anderson, Skye Toor, Lee Rainie & Aaron Smith, Public Attitudes Toward Political Engagement on Social Media, Pew Rsch. Ctr. (Jul. 11, 2018), https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2018/07/11/public-attitudes-toward-political-engagement-on-social-media/. ↑

- Id. See also, Brooke Auxier, Activism on Social Media Varies by Race and Ethnicity, Age, Political Party, Pew Rsch. Ctr. (July 13, 2020), https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/07/13/activism-on-social-media-varies-by-race-and-ethnicity-age-political-party/. ↑

- Anderson et al., supra note 5. ↑

- Id.; Gia Nardini Tracy Rank-Christman, Melissa G. Bublitz, Samantha N. N. Cross & Laura A. Peracchio, Together We Rise: How Social Movements Succeed, 31 J. Consumer Psych. 112, 124 (2020). ↑

- #MOVEME: A Guide to Social Movement & Social Media, https://moveme.berkeley.edu/project/arab-spring/; Tufekci, supra note 5, passim. ↑

- Kelsey Piper, Giving Tuesday, Explained, Vox (Nov. 30, 2020), https://www.vox.com/future-perfect/21727010/giving-tuesday-explained-charity-nonprofit. ↑

- Kerry Flynn, How #LoveWins On Twitter Became the Most Viral Hashtag Of the Same-Sex Marriage Ruling, Int’l Bus. Times (June 26, 2015), https://www.ibtimes.com/how-lovewins-twitter-became-most-viral-hashtag-same-sex-marriage-ruling-1986279. ↑

- Deen Freelon, Charlton D. McIlwain & Meredith D. Clark, Beyond the Hashtags: #Ferguson, #Blacklivesmatter, and the Online Struggle for Offline Justice, Ctr. for Media & Soc. Impact, 42-43 (Feb. 29, 2016), https://cmsimpact.org/resource/beyond-hashtags-ferguson-blacklivesmatter-online-struggle-offline-justice/. ↑

- See generally id.; see also Tufekci, supra note 5, 6-8. ↑

- See Philip Montgomery, Get Up, Stand Up, Wired (Nov. 2015), https://www.wired.com/2015/10/how-black-lives-matter-uses-social-media-to-fight-the-power/. ↑

- Janette Lehmann, Bruno Gonçalves, José J. Ramasco & Ciro Cattuto, Dynamical Classes of Collective Attention in Twitter, WWW ‘12: Proc. 21st Int’l Conf. on World Wide Web 251, 256 (2012); see also Zeynep Tufekci, The Boom-Bust Cycle of Social Media-Fueled Protests, MIT Center for Civic Media (Oct. 18, 2013). https://cms.mit.edu/podcast-zeynep-tufekci-boom-bust-cycle-social-media-fueled-protests/. ↑

- Alice E. Marwick, Status Update: Celebrity, Publicity, and Branding in the Social Media Age 143 (2013). ↑

- Cerise L. Glenn, Activism or “Slacktivism?”: Digital Media and Organizing for Social Change, 29 Commc’n Tchr. 81, 82 (2015). ↑

- James Dennis, Beyond Slacktivism: Political Participation on Social Media 4 (2019). ↑

- Tufekci, supra note 5, at 78-79. ↑

- Id. at 77. See also Jane Hu, The Second Act of Social Media Activism, New Yorker (Aug. 3, 2020), https://www.newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/the-second-act-of-social-media-activism. ↑

- See generally Tufekci, supra note 5; Gino Canella, Racialized Surveillance: Activist Media and the Policing of Black Bodies, 11 Commc’n, Culture & Critique 378 (2018). ↑

- See id. at 385 (“After an open records request, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) in Northern California discovered that the Fresno Police Department was using four social media applications—Geofeedia, LifeRaft, Media Sonar and Beware—to conduct online surveillance of BLM and its supporter; In another report, public records showed the Denver Police Department spent $30,000 for 30 subscriptions of Geofeedia, allowing the department to geo-locate social media posts emanating from specific events such as public demonstrations and marches actions BLM5280 conducts in order to disseminate its messages and raise public consciousness about police abuse.”). ↑

- For the Twitter data, we used the Twitter Streaming API# to collect posts containing the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter. While collection began in 2018, this study looks at posts (tweets, retweets, and quotes) from January 1, 2019 to November 15, 2020. We use these data to measure daily and overall volume of conversation and topics of discussion relevant to this essay. ↑

- See generally The #MeToo Research Collaboration, Georgetown’s Massive Data Institute and the Gender+ Justice Initiative, http://metoo.georgetown.domains/ (last visited May 8, 2020). ↑

- Guobin Yang, Narrative Agency in Hashtag Activism: The Case of #BlackLivesMatter, 4 Media & Commc’n 13, 15 (2016), https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers/472. ↑

- We did collect tweets with variants of the hashtag such as #BLM and #BlackLivesMatters. However, their overall volume was significantly less than that of #BlackLivesMatter during our period of study, so we focused our analysis on the main hashtag. ↑

- See Larry Buchanan, Quoctrung Bui & Jugal K. Patel, Black Lives Matter May Be the Largest Movement in U.S. History, N.Y. Times (July 3, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/07/03/us/george-floyd-protests-crowd-size.html; see also Monica Anderson, Michael Barthel, Andrew Perrin & Emily A. Vogels, #BlackLivesMatter surges on Twitter after George Floyd’s death, Pew Resch. Ctr. (June 10, 2020), https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/06/10/blacklivesmatter-surges-on-twitter-after-george-floyds-death/. ↑

- See Social Media Fact Sheet, Pew Rsch. Ctr. (Jun. 12, 2019), https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/social-media/; see also Jozie Nummi, Carly Jennings & Joe Feagin, #BlackLivesMatter: Innovative Black Resistance, 34 Socio. F. 1042, 1056 (2019). ↑

- Freelon et al., supra note 12, at 82 (“BLM borrowed many of its digital tactics from prior movements, including the development and independent distribution of new issue narratives, media criticism, systemic critiques, and enlisting well-known endorsers. But arguably the most substantial difference between it and its predecessors has to do with the nature of police brutality as an issue. Simply put, it is extremely well-suited to internet-based activism. Unlike wealth or income inequality, police brutality is concrete, discrete in its manifestations, and above all, visual. Hashtagged names and other digital memorials remind the public of the irreplaceable losses felt by the victims’ families. The frighteningly common occurrence of these killings means that activists and journalists have no shortage of occasions to discuss the issue. And the video and photographic evidence that is often available provokes public outrage and disgust . . . “). ↑